| Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Jewish–Roman War | ||||||||||

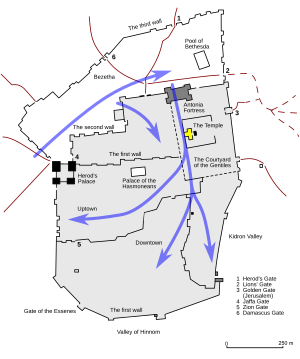

Progress of the Roman army during the siege. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

| Titus |

Simon Bar Giora | |||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

| 70,000 | 15–20,000 | 10,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

| Unknown | 15-20,000 | 10,000 | ||||||||

|

According to Josephus, 1.1 million non-combatants died in Jerusalem, mainly as a result of the violence and famine. Many of the casualties were observant Jews from across the world such as Babylon and Egypt who had travelled to Jerusalem wanting to celebrate the yearly Passover but instead got trapped in the chaotic siege.[1] He also tells us that 97,000 were enslaved.[1] Matthew White, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things (Norton, 2012) p.52,[2] estimates the combined death toll[Clarification needed] for the First and Third Roman Jewish Wars as being approximately 350,000 | ||||||||||

The Siege of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War. The Roman army, led by the future Emperor Titus, with Tiberius Julius Alexander as his second-in-command, besieged and conquered the city of Jerusalem, which had been controlled by Judean rebel factions since 66 CE, following the Jerusalem riots of 66, when the Judean Free Government was formed in Jerusalem.

The siege ended on August 30, 70 CE[3] with the burning and destruction of its Second Temple, and the Romans entered and sacked the Lower City. The destruction of both the first and second temples is still mourned annually as the Jewish fast Tisha B'Av. The Arch of Titus, celebrating the Roman sack of Jerusalem and the Temple, still stands in Rome. The conquest of the city was complete on September 8, 70 CE.

Siege[]

| |||||||||||||||

Despite early successes in repelling the Roman sieges, the Zealots fought amongst themselves, and they lacked proper leadership, resulting in poor discipline, training, and preparation for the battles that were to follow. At one point they destroyed the food stocks in the city, a drastic measure thought to have been undertaken perhaps in order to enlist a merciful God's intervention on behalf of the besieged Jews,[4] or as a stratagem to make the defenders more desperate, supposing that was necessary in order to repel the Roman army.[5]

Titus began his siege a few days before Passover,[6] surrounding the city, with three legions (V Macedonica, XII Fulminata, XV Apollinaris) on the western side and a fourth (X Fretensis) on the Mount of Olives to the east.[7][8] If the reference in his Jewish War at 6:421 is to Titus' siege, though difficulties exist with its interpretation, then at the time, according to Josephus, Jerusalem was thronged with many people who had come to celebrate Passover.[9] The thrust of the siege began in the west at the Third Wall, north of the Jaffa Gate. By May, this was breached and the Second Wall also was taken shortly afterwards, leaving the defenders in possession of the Temple and the upper and lower city. The Jewish defenders were split into factions: John of Gischala's group murdered another faction leader, Eleazar ben Simon, whose men were entrenched in the forecourts of the Temple.[6] The enmities between John of Gischala and Simon bar Giora were papered over only when the Roman siege engineers began to erect ramparts. Titus then had a wall built to girdle the city in order to starve out the population more effectively. After several failed attempts to breach or scale the walls of the Fortress of Antonia, the Romans finally launched a secret attack, overwhelming the sleeping Zealots and taking the fortress by late July.[6]

After Jewish allies killed a number of Roman soldiers, Titus sent Josephus, the Jewish historian, to negotiate with the defenders; this ended with Jews wounding the negotiator with an arrow, and another sally was launched shortly after. Titus was almost captured during this sudden attack, but escaped.

Catapulta, by Edward Poynter (1868). Siege engines such as this were employed by the Roman army during the siege.

Overlooking the Temple compound, the fortress provided a perfect point from which to attack the Temple itself. Battering rams made little progress, but the fighting itself eventually set the walls on fire; a Roman soldier threw a burning stick onto one of the Temple's walls. Destroying the Temple was not among Titus' goals, possibly due in large part to the massive expansions done by Herod the Great mere decades earlier. Titus had wanted to seize it and transform it into a temple dedicated to the Roman Emperor and the Roman pantheon. However, the fire spread quickly and was soon out of control. The Temple was captured and destroyed on 9/10 Tisha B'Av, at the end of August, and the flames spread into the residential sections of the city.[6][8] Josephus described the scene:

As the legions charged in, neither persuasion nor threat could check their impetuosity: passion alone was in command. Crowded together around the entrances many were trampled by their friends, many fell among the still hot and smoking ruins of the colonnades and died as miserably as the defeated. As they neared the Sanctuary they pretended not even to hear Caesar's commands and urged the men in front to throw in more firebrands. The partisans were no longer in a position to help; everywhere was slaughter and flight. Most of the victims were peaceful citizens, weak and unarmed, butchered wherever they were caught. Round the Altar the heaps of corpses grew higher and higher, while down the Sanctuary steps poured a river of blood and the bodies of those killed at the top slithered to the bottom.[10]

Josephus's account absolves Titus of any culpability for the destruction of the Temple, but this may merely reflect his desire to procure favor with the Flavian dynasty.[10][11]

The Roman legions quickly crushed the remaining Jewish resistance. Some of the remaining Jews escaped through hidden underground tunnels and sewers, while others made a final stand in the Upper City.[12] This defense halted the Roman advance as they had to construct siege towers to assail the remaining Jews. Herod's Palace fell on September 7, and the city was completely under Roman control by September 8.[13][14] The Romans continued to pursue those who had fled the city.

Destruction of Jerusalem[]

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem, by David Roberts (1850).

Stones from the Western Wall of the Temple Mount (Jerusalem) thrown onto the street by Roman soldiers on the Ninth of Av, 70

The account of Josephus described Titus as moderate in his approach and, after conferring with others, ordering that the 500-year-old Temple be spared. According to Josephus, it was the Jews who first used fire in the Northwest approach to the Temple to try and stop Roman advances. Only then did Roman soldiers set fire to an apartment adjacent to the Temple, a conflagration which the Jews subsequently made worse.[15]

Josephus had acted as a mediator for the Romans and, when negotiations failed, witnessed the siege and aftermath. He wrote:

Now as soon as the army had no more people to slay or to plunder, because there remained none to be the objects of their fury (for they would not have spared any, had there remained any other work to be done), [Titus] Caesar gave orders that they should now demolish the entire city and Temple, but should leave as many of the towers standing as they were of the greatest eminence; that is, Phasaelus, and Hippicus, and Mariamne; and so much of the wall enclosed the city on the west side. This wall was spared, in order to afford a camp for such as were to lie in garrison [in the Upper City], as were the towers [the three forts] also spared, in order to demonstrate to posterity what kind of city it was, and how well fortified, which the Roman valor had subdued; but for all the rest of the wall [surrounding Jerusalem], it was so thoroughly laid even with the ground by those that dug it up to the foundation, that there was left nothing to make those that came thither believe it [Jerusalem] had ever been inhabited. This was the end which Jerusalem came to by the madness of those that were for innovations; a city otherwise of great magnificence, and of mighty fame among all mankind.[16]

And truly, the very view itself was a melancholy thing; for those places which were adorned with trees and pleasant gardens, were now become desolate country every way, and its trees were all cut down. Nor could any foreigner that had formerly seen Judaea and the most beautiful suburbs of the city, and now saw it as a desert, but lament and mourn sadly at so great a change. For the war had laid all signs of beauty quite waste. Nor had anyone who had known the place before, had come on a sudden to it now, would he have known it again. But though he [a foreigner] were at the city itself, yet would he have inquired for it.[17]

Josephus claims that 1.1 million people were killed during the siege, of which a majority were Jewish. Josephus attributes this to the celebration of Passover which he uses as rationale for the vast number of people present among the death toll.[18] Armed rebels, as well as the frail citizens, were put to death. All of Jerusalem's remaining citizens became Roman prisoners. After the Romans killed the armed and elder people, 97,000 were still enslaved, including Simon bar Giora and John of Giscala.[19] Simon bar Giora was executed, and John of Giscala was sentenced to life imprisonment. Of the 97,000, thousands were forced to become gladiators and eventually expired in the arena. Many others were forced to assist in the building of the Forum of Peace and the Colosseum. Those under 17 years of age were sold into servitude.[20] Josephus' death toll assumptions are rejected as impossible by modern scholarship, since around the time about a million people lived in Palestine, about half of them were Jews, and sizable Jewish populations remained in the area after the war was over, even in the hard-hit region of Judea.[21] Titus and his soldiers celebrated victory upon their return to Rome by parading the Menorah and Table of the Bread of God's Presence through the streets. Up until this parading, these items had only ever been seen by the high priest of the Temple. This event was memorialized in the Arch of Titus.[18][20]

Many fled to areas around the Mediterranean. According to Philostratus writing in the early years of the 3rd Century, Titus reportedly refused to accept a wreath of victory, saying that the victory did not come through his own efforts but that he had merely served as an instrument of God's wrath.[22]

Commemoration[]

Roman[]

- Judaea Capta coinage: Judaea Capta coins were a series of commemorative coins originally issued by the Roman Emperor Vespasian to celebrate the capture of Judaea and the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem by his son Titus in 70 CE during the First Jewish Revolt.

- Temple of Peace: In 75 CE, the Temple of Peace, also known as the Forum of Vespasian, was built under Emperor Vespasian in Rome. The monument was built to celebrate the conquest of Jerusalem and it is said to have housed the Menorah from Herod's Temple.[23]

- Flavian Amphitheater: Otherwise known as the Colosseum built from 70 to 80. Archaeological discoveries have found a block of travertine that bears dowel holes that show the Jewish Wars financed the building of the Flavian Amphitheatre.[24]

- Arch of Titus: c. 82 CE, Roman Emperor Domitian constructed the Arch of Titus on Via Sacra, Rome, to commemorate the capture and siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, which effectively ended the Great Jewish Revolt, although the Romans did not achieve complete victory until the fall of Masada in 73 CE.

Jewish[]

- Tisha B'Av

Perceptions and historical legacy[]

The Jewish Amoraim attributed the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem as punishment from God for the "baseless hatred" that pervaded Jewish society at the time.[25] Many Jews in despair are thought to have abandoned Judaism for some version of paganism, many others sided with the growing Christian sect within Judaism.[21]:196–198

The destruction was an important point in the separation of Christianity from its Jewish roots: many Christians responded by distancing themselves from the rest of Judaism, as reflected in the Gospels which some believe portray Jesus as anti-Temple and view the destruction of the temple as punishment for rejection of Jesus.[21]:30–31

In later art[]

'Siege and destruction of Jerusalem', La Passion de Nostre Seigneur c.1504

The war in Judaea, particularly the siege and destruction of Jerusalem, have inspired writers and artists through the centuries. The bas-relief in the Arch of Titus has been influential in establishing the Menorah as the most dramatic symbol of the looting of the Second Temple.

- Siege of Jerusalem A fourteenth century Middle English poem

- The Franks Casket. The back side of the casket depicts the Siege of 70.

- The Destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem by Nicolas Poussin (1637). Oil on canvas, 147 × 198.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Depicts the destruction and looting of the Second Temple by the Roman army led by Titus.

- The Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1846). Oil on canvas, 585 × 705 cm. Neue Pinakothek, Munich. An allegorical depiction of the destruction of Jerusalem, dramatically centered on the figure of the High Priest, with Titus entering from the right.

- The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans Under the Command of Titus, 70 by David Roberts (1850). Oil on canvas, 136 × 197 cm. Private collection. Depicts the burning and looting of Jerusalem by the Roman army under Titus.

- The Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem by Francesco Hayez (1867). Oil on canvas, 183 × 252 cm. Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Venice. Depicts the destruction and looting of the Second Temple by the Roman army.

See also[]

- Council of Jamnia

- Flight to Pella

- Herod's Temple

- Holyland Model of Jerusalem

- Kamsa and Bar Kamsa

- Preterism

- Robinson's Arch

- Royal Stoa (Jerusalem)

- Siege of Jerusalem

- Solomon's Temple

- Fiscus Judaicus

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Template:Cite Josephus

- ↑ "Atrocity statistics from the Roman Era". Necrometrics.com. http://necrometrics.com/romestat.htm. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Matthew Bunson A Dictionary of the Roman Empire p.212

- ↑ Nachman Ben-Yehuda Theocratic Democracy: The Social Construction of Religious and Secular Extremism, Oxford University Press, 2010 p. 91.

- ↑ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). Jewish Literacy. NY: William Morrow and Co.. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-great-revolt-66-70-ce. Retrieved 11 December 2017. "While the Romans would have won the war in any case, the Jewish civil war both hastened their victory and immensely increased the casualties. One horrendous example: In expectation of a Roman siege, Jerusalem's Jews had stockpiled a supply of dry food that could have fed the city for many years. But one of the warring Zealot factions burned the entire supply, apparently hoping that destroying this "security blanket" would compel everyone to participate in the revolt. The starvation resulting from this mad act caused suffering as great as any the Romans inflicted."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest, Routledge, 2003 pp.129-130.

- ↑ Sheppard, Si. The Jewish Revolt AD 66?74. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781780961842. https://books.google.com/books?id=b1KbCwAAQBAJ&dq=The+Jewish+Revolt+AD+66–74&redir_esc=y.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Barbara Levick, Vespasian, Routledge 1999, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Frederico M. Colautti, Passover in the Works of Flavius Josephus, BRILL 2002 pp. 115–131.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in Antiquity, Routledge (1995) 2013 pp.191-192.

- ↑ "A.D. 70 Titus Destroys Jerusalem" (in en). Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church. http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-28/ad-70-titus-destroys-jerusalem.html.

- ↑ Peter J. Fast (November 2012). 70 A. D.: A War of the Jews. AuthorHouse. p. 761. ISBN 978-1-4772-6585-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=im_Wh477dksC&pg=PA761.

- ↑ Si Sheppard (20 October 2013). The Jewish Revolt AD 66–74. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-185-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=S6qHCwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Dr Robert Wahl (2006). Foundations of Faith. David C Cook. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7814-4380-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=eYSwPqeP6qUC&pg=PA103.

- ↑ Mireille Hadas-Lebel (2006). Jerusalem Against Rome. Peeters Publishers. p. 86.

- ↑ Template:Cite Josephus

- ↑ Template:Cite Josephus

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goldberg, G J. "Chronology of the War According to Josephus: Part 7, The Fall of Jerusalem". http://www.josephus.org/FlJosephus2/warChronology7Fall.html.

- ↑ Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.9.3

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Titus' Siege of Jerusalem - Livius" (in en). http://www.livius.org/articles/concept/roman-jewish-wars/roman-jewish-wars-4/?.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Schwartz, Seth (1984). "Political, social and economic life in the land of Israel". The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. https://books.google.com/books?id=BjtWLZhhMoYC.

- ↑ Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6.29

- ↑ "Cornell.edu". Cals.cornell.edu. http://www.cals.cornell.edu/cals/public/comm/pubs/als-news/2003-april/ancient-parks.cfm. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ Alföldy, Géza (1995). "Eine Bauinschrift Aus Dem Colosseum.". pp. 195–226.

- ↑ Yoma, 9b

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Siege of Jerusalem (70). |

The Jewish History Resource Center: Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The original article can be found at Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE) and the edit history here.