| Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Southern Song before Mongol World conquests | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Song dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ögedei Tsagaan Khochu Töregene Güyük Khan Möngke Khan (possibly †) Kublai Bayan Aju Arikhgiya Zhang Hongfan |

Emperor Lizong of Song Emperor Duzong of Song Emperor Gong of Song Emperor Duanzong of Song Emperor Huaizong of Song† Jia Sidao Lü Wenhuan Li Tingzhi Zhang Shijie Wen Tianxiang | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| More than 450,000 (including the Mongols, the Jurchens, the Chinese, the Alans and the Turkics) | More than 1,500,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Very heavy but much fewer than the Song | Over 10,000,000 including civilians | ||||||

| |||||

The Mongol conquest of the Southern Song dynasty under Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294) was the final step for the Mongols to rule the whole of China. It is also considered the Mongol Empire's last great military achievement.[1]

Background[]

Before the Mongol–Jin War escalated, an envoy from Song China arrived at the court of the Mongols, perhaps to negotiate a united offensive against the Jin dynasty, who the Song had previously fought during the Jin–Song Wars. Although Genghis Khan refused, on his death in 1227 he bequeathed a plan to attack the Jin capital by passing through Song territory. Subsequently, a Mongol ambassador was killed by the Song governor in uncertain circumstances.[2] Before receiving any explanation, the Mongols marched through Song territory to enter the Jin's redoubt in Henan. In 1233 the Song dynasty finally became an ally of the Mongols, who agreed to share territories south of the Yellow River with the Song. Song general Meng Gong defeated the Jin general Wu Xian and directed his troops to besiege the city of Caizhou, to which the last emperor of the Jurchen had fled. With the help of the Mongols, the Song armies were finally able to extinguish the Jin dynasty that had occupied northern China for more than a century. A year later, the Song generals fielded their armies to occupy the old capitals of the Song, but they were completely repelled by the Mongol garrisons under Tachir, a descendant of Boorchu, who was a famed companion of Genghis Khan. Thus the Mongol troops, headed by sons of the Ögedei Khan, started their slow but steady invasion of the south. The Song forces resisted fiercely, which resulted in a prolonged set of campaigns; however, the primary obstacles to the prosecution of their campaigns was unfamiliar terrain that was inhospitable to their horses, new diseases, and the need to wage naval battles, a form of warfare completely alien to the masters of the steppe. This combination resulted in one of the most difficult and prolonged wars of the Mongol conquests.[3] The Chinese offered the fiercest resistance of among all the Mongols fought, the Mongols required every single advantage they could gain and "every military artifice known at that time" in order to win.[4]

Emperor Lizong of Song

First stage (1235–48)[]

From 1235 on, the Mongol general Kuoduan Hequ started to attack the region of Sichuan through the Chengdu plain. The occupation of this region had often been an important step for the conquest of the south. The important city of Xiangyang, the gateway to the Yangtze plain, which was defended by the Song general Cao Youwen, capitulated in 1236.[5] In the east, meanwhile, Song generals like Meng Gong and Du Guo withstood the pressure of the Mongol armies under Kouwen Buhua because the main Mongol forces were at that time moving towards Europe. In Sichuan, governor Yu Jie adopted the plan of the brothers Ran Jin and Ran Pu to fortify important locations in mountainous areas, like Diaoyucheng (modern Hechuan/Sichuan). From this point, Yu Jie was able to hold Sichuan for a further ten years. In 1239, General Meng defeated the Mongols and retook Xiangyang, contesting Sichuan against the Mongols for years.[6] The only permanent gain was Chengdu for the Mongols in 1241. In the Huai River area, the Mongol Empire's commanders remained on the defensive, taking few major Song cities, although Töregene and Güyük Khan ordered their generals to attack the Song.[7]

The conflicts between the Mongols and the Song troops took place in the area of Chengdu. When Töregene sent her envoys to negotiate peace, the Song imprisoned them.[8] The Mongols captured Hangzhou and invaded Sichuan in 1242. Their commanders ordered Zhang Rou and Chagaan (Tsagaan) to attack the Song. When they pillaged Song territory, the Song court sent a delegation to negotiate a ceasefire. Chagaan and Zhang Rou returned north after the Mongols accepted the terms.[9]

An account was given of the Mongol attack on Nanjing, and of the Chinese defenders using gunpowder against the Mongols: "As the Mongols had dug themselves pits under the earth where they were sheltered from missiles, we decided to bind with iron the machines called chen-t'ien-lei. . . and lowered them into the places"[10]

Second stage (1251–60)[]

The Mongol attacks on Southern Song China intensified with the election of Möngke as Great Khan in 1251. Passing through the Chengdu Plain in Sichuan, the Mongols conquered the Kingdom of Dali in modern Yunnan in 1253. Möngke's brother Kublai and general Uriyangqadai pacified Yunnan and Tibet and invaded the Trần dynasty in Vietnam. The Mongols besieged Ho-chiou and lifted the siege very soon in 1254.

In October 1257 Möngke set out for South China and fixed his camps near the Liu-pan mountains in May. He entered Sichuan in 1258 with two-thirds of the Mongol strength. In 1259 Möngke died of cholera or dysentery during the battle of Diaoyucheng that was defended by Wang Jian. The Chinese general Jia Sidao collaborated with Kublai and took the opportunity of Möngke's death to occupy Sichuan as subject of the Mongols.

The central government of the Southern Song meanwhile was unable to cope with the challenge of the Mongols and new peasant uprisings in the region of modern Fujian led by Yan Mengbiao and Hunan. The court of Emperor Lizong was dominated by consort clans, Yan and Jia, and the eunuchs Dong Songchen and Lu Yunsheng. In 1260 Jia Sidao became chancellor who took control over the new emperor Zhao Qi (posthumous title Song Duzong) and expelled his opponents like Wen Tianxiang and Li Fu. Because the financial revenue of the late Southern Song state was very low, Jia Sidao tried to reform the regulations for the merchandise of lands with his state field law.

Gunpowder weapons like the t'u huo ch'iang were deployed by the Chinese against the Mongol forces. The weapon consisted of firing bullets from bamboo tubes.[11]

Surrender of Song China (1268–76)[]

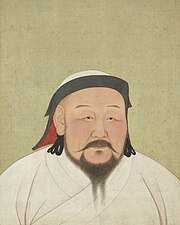

Kublai Khan, the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire and Emperor of the Yuan dynasty. Painting from 1294.

In 1260 Kublai was elected Great Khan of the Mongols and founded the Yuan dynasty in 1271. The skirmishes of the early 1260s led to a major confrontation in Diaoyu, Sichuan in 1265. The Mongols defeated the Song land and naval armies and captured more than 100 ships.[12] The Chinese utilized gunpowder weapons for defence during the conquest.[13]

Kublai did eventually conquer the south with a great deal of tribulation. First there was the Toluid Civil War with Ariq Böke, who had been left in command of the north and stationed in the Mongol capital, Karakorum; then in 1268,[14] there was the Mongol advance stopped at the city of Xiangyang situated on the Han river controlling access to the Yangtze river, the gateway to Hangzhou. This city was linked to the city of Fencheng situated on the opposite bank connected by a pontoon bridge spanning the river Han. The walls of Xiangyang were some six to seven meters thick encompassing an area of five kilometers wide,the main entrances leading out to a waterway impossible to ford in the summer, in the winter an impassable swamp and series of ponds and mud flats.

The defenders of twin-cities, Xiangyang and Fancheng, attempted to break the siege but the Mongols under Aju defeated them each time. The Mongols crushed all reinforcements from the Song, each numbering in the thousands.[15] After this defeat, Aju asked Kublai, the Emperor of the Mongol Empire, for the powerful siege machines of the Ilkhanate. Ismaildisambiguation needed and Al-aud-Din from Iraq arrived in South China to construct a new type of trebuchet which used explosive shells. These Persian engineers built mangonels and trebuchets for the siege.[16] Explosive shells had been in use in China for centuries but what was new was the counterweight type of trebuchet as opposed to the torsion type giving greater range and accuracy as it was easier to judge the weight of the counter weight than the torsion generated by repeated windings.[17] The counterweight trebutchet built by the Persians from Mosul were longer in range, and assisted in destroying Fancheng.[18] Chinese and Muslim engineers operated artillery and siege engines for the Mongol armies.[19] The design was taken from those used by Hulagu to batter down the walls of Baghdad. The Chinese were the first to invent the traction trebuchet, now they faced Muslim designed counterweight trebuchets in the Mongol army. The Chinese responded by building their own counterweight trebuchets, an account from the Chinese said "In 1273 the frontier cities had all fallen. But Muslim trebuchets were constructed with new and ingenious improvements, and different kinds became available, far better than those used before."[20]

Both the Song and Mongol forces used "thunder crash" bombs during the siege, a type of gunpowder weapon. The Mongols also utilized siege crossbows and traction trebuchets. The Song forces used fire arrows and fire lances in addition to their own "thunder crash" bombs. The Song forces also used paddle ships.[21] Siege crossbows and firebombs were also deployed on Song ships against Mongol forces, in addition to fire lances.[22] The name of the bombs in Chinese was Zhen tian lei; they were made from cast iron and filled with gunpowder. The Song forces delivered them to the enemy via trebuchets. Armor made out of iron could be penetrated by pieces of the bomb after the explosion, which had a 50 kilometer noise range.[23]

Political infighting in the Song also caused the fall of Xiangyang and Fancheng, due to the power of the Lu family. Many questioned their allegiance to the Song, and the Emperor barred Jia Sidao himself from the command. Li Tingzhi, an enemy of the Lu family, was appointed commander. Jia permitted the Lu to ignore Li's orders, resulting in a fractious command. Li was then unable to relieve Xiangyang and Fancheng, managing only temporary resupply during several breaks in the siege.[24]

Bayan of the Baarin, the Mongol commander, then sent half of his force up-river to wade to the south bank in order to build a bridge across to take the Yang lo fortress. Three thousand Song boats came up the Han river and were repulsed; fifty boats destroyed with 2,000 dead. Xiangyang's commander then surrendered to the Mongol commander. The entire force including the surrendering commander sailed down the Yangtze, and the forts along the way fell, as this commander, now allied with the Mongols, had also commanded many of the down river garrisons. In 1270, Kublai ordered the construction of five thousand ships. Three years later, an additional two thousand ships were ordered built; these would carry about 50,000 troops to give battle to the Song. In 1273, Fancheng capitulated, the Mongols putting the entire population to the sword to terrorize the inhabitants of Xiangyang. After the surrender of the city of Xiangyang, several thousand ships were deployed. The Song fleet, despite their deployment as a coastal defense fleet or coast guard more than an operational navy, was more than a match for the Mongols. Under his great general Bayan, Khublai unleashed a riverine attack upon the defended city of Xiangyang on the Han River. The Mongols prevailed, ultimately, but it would take five more years of hard combat to do so.[25]

By 1273, the Mongols emerged victorious on the Han River. The Yangtse River was opened for a large fleet that could conquer the Southern Song empire. A year later, the child-prince Zhao Xian was made emperor. Resistance continued, resulting in Bayan's massacre of the inhabitants of Changzhou in 1275 and mass suicide of the defenders at Changsha in January 1276. When the Yuan Mongol-Chinese troops and fleet advanced and one prefecture after the other submitted to the Yuan, Jia Sidao offered his own submission, but the Yuan chancellor Bayan refused. The last contingents of the Song empire were heavily defeated, the old city of Jiankang (Jiangsu) fell, and Jia Sidao was killed. The capital of Song, Lin'an (Hangzhou), was defended by Wen Tianxiang and Zhang Shijie. When Bayan and Dong Wenbing camped outside Lin'an in February 1276, the Song Grand Empress Dowager Xie and Empress Dowager Quan surrendered the underage Emperor Gong of Song along with the imperial seal. Emperor Gong abdicated, but faithful loyalists like Zhang Jue, Wen Tianxiang, Zhang Shijie and Lu Xiufu successively enthroned the emperor's younger brothers Zhao Shi and Zhao Bing. Zhao Shi was enthroned as Emperor Duanzong of Song far from the capital in the region of Fuzhou but he died soon afterwards on the flight southwards into modern Guangdong. Zhao Bing was enthroned as Emperor Huaizong of Song on Lantau Island, Hong Kong. On March 19, 1279 the Mongols defeated the last of the Song forces at the naval Battle of Yamen. After the battle, as a last defiant act against the invaders, Lu Xiufu embraced the eight-year-old emperor and the pair leapt to their deaths from Mount Ya, thus marking the extinction of the Southern Song.[26]

Last stand of the Song loyalists (1276–79)[]

Emperor Bing, the last Song emperor claimant.

Empress Dowager Xie had secretly sent the child emperor's two younger brothers to Fuzhou. The strongholds of the Song loyalists fell one by one: Yangzhou in 1276, Chongqing in 1277 and Hezhou in 1279. The loyalists fought the Mongols in the mountainous Fujian–Guangdong–Jiangxi borderland. In February 1279, Wen Tianxiang, one of the Song loyalists, was captured and executed at the Yuan capital Dadu.

The end of the Mongol-Song war occurred on 19 March 1279, when 1000 Song warships faced a fleet of 300 to 700 Yuan Mongol warships at Yamen. The Yuan fleet was commanded by Zhang Hongfan (1238–1280), a northern Chinese, and Li Heng (1236–1285), a Tangut. Catapults as a weapon system were rejected by Kublai's court, for they feared the Song fleet would break out if they used such weapons. Instead, they developed a plan for a maritime siege, in order to starve the Song into submission.

But at the outset, there was a defect in the Song tactics that would later be exploited by Yuan at the conclusion of the battle. The Song wanted a stronger defensive position, and the Song fleet "roped itself together in a solid mass[,]" in an attempt to create a nautical skirmish line. Results were disastrous for the Song: they could neither attack nor maneuver. Escape was also impossible, for the Song warships lacked any nearby base. On 12 March, a number of Song combatants defected to the Mongol side. On 13 March, a Song squadron attacked some of the Mongols' northern patrol boats. If this action was an attempted breakout, it failed. By 17 March, Li Heng and Zhang Hongfan opted for a decisive battle. Four Mongol fleets moved against the Song: Li Heng attacked from the north and northwest; Zhang would proceed from the southwest; the last two fleets attacked from the south and west. Weather favored the Mongols that morning. Heavy fog and rain obscured the approach of Li Heng's dawn attack. The movement of the tide and the southwestern similarly benefited the movement of the Mongol fleet which, in short order, appeared to the north of the Song. It was an unusual attack in that the Mongol fleet engaged the Song fleet stern first.

Prior to the battle, the Mongols constructed archery platforms for their marines. The position enabled the archers to direct a higher, more concentrated rate of missile fire against the enemy. Fire teams of seven or eight archers manned these platforms, and they proved devastatingly effective as the battle commenced at close quarter.

Li Heng's first attack cut the Song rope that held the Chinese fleet together. Fighting raged in close quarters combat. Before midday, the Song lost three of their ships to the Mongols. By forenoon, Li's ships broke through the Song's outer line, and two other Mongol squadrons destroyed the Song formation in the northwest corner. Around this time, the tide shifted; Li's ships drifted to the opposite direction, the north.

The Mongol Empire included all China. The gray area is the later Timurid empire

The Song believed that the Mongols were halting the attack and dropped their guard. Zhang Hongfan's fleet, riding the northern current, then attacked the Song ships. Zhang was determined to capture the Song admiral, Zuo Tai. The Yuan flagship was protected by shields to negate the Song missile fire. Later, when Zhang captured the Song flagship, his own vessel was riddled with arrows. Li Heng's fleet also returned to the battle. By late afternoon, the battle was over, and the last of the Song navy surrendered.

The ruling elite were unwilling to submit to Mongol rule, and opted for death by suicide. The Song councilor, who had been tasked with holding the infant child-emperor of the Song in his arms during the battle, also elected to join the Song leaders in death. It is uncertain whether he or others decided that the infant Emperor should die as well. Presumably, the councilor did not wish to see a baby trampled to death in Mongol tradition, as may have been done to the child-emperor. It was Mongol tradition that no royal blood should touch the earth; therefore many of their royal captives were executed by methods that did not break this taboo. A common method of execution was to roll the captive in a rug, and march troops on horseback over the bound victim, trampling him to death. The councilor therefore jumped into the sea, still holding the child in his arms. Tens of thousands of Song officials and women threw themselves into the sea and drowned. The last Song emperor died with his entourage, held in the arms of his councilor. With his death, the final remnants of the Song dynasty were eliminated. The victory of this naval campaign marked the completion of Kublai's conquest of China, and the onset of the consolidated Mongol Yuan dynasty.

Notes[]

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.509

- ↑ Henry Hoyle Howorth, Ernest George Ravenstein History of the Mongols, p.228

- ↑ Nicolle, David; Hook, Richard (1998). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane (illustrated ed.). Brockhampton Press. p. 57. ISBN 1-86019-407-9. http://books.google.com/books?ei=1AfUTtfIIqbf0QHY-ukW&ct=result&id=OgQXAQAAIAAJ&dq=For+his+part+Kublai+dedicated+himself+totally+to+the+task%2C+but+it+was+still+to+be+the+Mongol%27s+thoughest+war.+The+Sung+Chinese+showed+themselves+to+be+the+most+resilient+of+foes.+Southern+China+was+not+only+densely+populated+and+full+of+strongly+walled+cities.+It+was+also+a+land+of+mountain+ranges+and+wide+fast-flowing&q=+chinese+resilient+foes. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "For his part Kublai dedicated himself totally to the task, but it was still to be the Mongol's toughest war. The Sung Chinese showed themselves to be the most resilient of foes. Southern China was not only densely populated and full of strongly walled cities. It was also a land of mountain ranges and wide fast-flowing"

- ↑ L. Carrington Goodrich (2002). A Short History of the Chinese People (illustrated ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 173. ISBN 0-486-42488-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=BZf_L1V7NLUC&pg=PA173. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "Unquestionably in the Chinese the Mongols encountered more stubborn opposition and better defense than any of their other opponents in Europe and Asia had shown. They needed every military artifice known at that time, for they had to fight in terrain that was difficult for their horses, in regions infested with diseases fatal to large numbers of their forces, and in boats to which they were not accustomed."

- ↑ John Man Kublai Khan, p.158

- ↑ René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia (reprint ed.). Rutgers University Press. p. 282. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=CHzGvqRbV_IC&pg=PA282. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ C. P. Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire', p.509

- ↑ Jeremiah Curtin The Mongols A History, p.343

- ↑ J.Bor Mongol hiiged Eurasiin diplomat shastir, vol.II, p.224

- ↑ (the University of Michigan)John Merton Patrick (1961). Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Volume 8, Issue 3 of Monograph series. Utah State University Press. p. 10. http://books.google.com/books?id=6GMFAAAAMAAJ&q=A+Chinese+annalist+describes+the+use+of+these+gunpowder+weapons+at+Nanking+as+follows:+%22As+the+Mongols+had+dug+themselves+pits+under+the+earth+where+they+were+sheltered+from+missiles,+we+decided+to+bind+with+iron+the+machines+called&dq=A+Chinese+annalist+describes+the+use+of+these+gunpowder+weapons+at+Nanking+as+follows:+%22As+the+Mongols+had+dug+themselves+pits+under+the+earth+where+they+were+sheltered+from+missiles,+we+decided+to+bind+with+iron+the+machines+called&hl=en&ei=h6XVTvWIMunl0QGI4fH3AQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "A Chinese annalist describes the use of these gunpowder weapons at Nanking as follows: "As the Mongols had dug themselves pits under the earth where they were sheltered from missiles, we decided to bind with iron the machines called chen-t'ien-lei. . . and lowered them into the places"

- ↑ (the University of Michigan)John Merton Patrick (1961). Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Volume 8, Issue 3 of Monograph series. Utah State University Press. p. 14. http://books.google.com/books?ei=7GQzTv7dFNPTgAe1mdzrDA&ct=result&id=6GMFAAAAMAAJ&dq=battle+of+mohi+chinese+gunpowder&q=chinese++artillery+tubes+shot+bulets+. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "overthrown, as we shall see — since the final counter-offensive launched by the Chinese against their Mongol overlords of the Yuan dynasty is a story in which artillery features significantly. By 1259 at least, if not earlier during the first Mongol invasions, the Chinese were using tubes that shot bullets. The t'u huo ch'iang ("rushing- forth fire- gun") was a long bamboo tube into which bullets in the true sense (tzu-k'o)"

- ↑ Warren I. Cohen East Asia at the center: four thousand years of engagement with the world, p.136

- ↑ (the University of Michigan)Reader's Digest Association (1985). Reader's digest almanac and yearbook. Reader's Digest Association.. p. 288. ISBN 0-89577-201-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=UAkwAAAAMAAJ&q=1269-73+Gunpowder+explosives+first+used+in+war:+Chinese+defender?+of+cities+in+Yangtze+River+Valley+use+explosives+against+Mongol+Invaders&dq=1269-73+Gunpowder+explosives+first+used+in+war:+Chinese+defender?+of+cities+in+Yangtze+River+Valley+use+explosives+against+Mongol+Invaders&hl=en&ei=0HMzTrWbBqP50gGQh92eDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "1269-73 Gunpowder explosives first used in war: Chinese defenders of cities in Yangtze River Valley use explosives against Mongol Invaders"

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull, Wayne Reynolds (2003). Mongol Warrior 1200-1350 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 1-84176-583-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=KTTELJ9N0XUC&pg=PA64. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ John Man Kublai Khan, p.168

- ↑ Jasper Becker (2008). City of heavenly tranquility: Beijing in the history of China (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-19-530997-9. http://books.google.com/books?ei=5fLhTZSdHZTpgAel0-nHBg&ct=result&id=UOiGAAAAMAAJ&dq=These+siege+engines+could+accurately+lob+huge+missiles+capable+of+demolishing+stone+castles+and+they+quickly+knocked+down+Xianyang%27s+mud+walls&q=xianyang+foreign+engineers+persia+mangonels+catapults. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull, Steve Noon (2009). Chinese Walled Cities 221 BC-AD 1644 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 1-84603-381-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=ug_twStv-4sC&pg=PA53. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Michael E. Haskew, Christer Joregensen, Eric Niderost, Chris McNab (2008). Fighting techniques of the Oriental world, AD 1200-1860: equipment, combat skills, and tactics (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 190. ISBN 0-312-38696-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=1fb7tBwv4ZYC&pg=PA190. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Grousset 1970, p. 283.

- ↑ Stephen R. Turnbull (2003). Genghis Khan & the Mongol conquests, 1190-1400 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 1-84176-523-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=N2MMD0yfxyAC&pg=PA63. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull (2002). Siege weapons of the Far East: AD 960-1644 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 1-84176-340-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=0TjxaHltoY0C&pg=PA12. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Stephen R. Turnbull (2003). Genghis Khan & the Mongol conquests, 1190-1400 (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 1-84176-523-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=N2MMD0yfxyAC&pg=PA63. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Matthew Bennett (2008). Matthew Bennett. ed. The Hutchinson dictionary of ancient & medieval warfare. Taylor & Francis. p. 356. ISBN 1-57958-116-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=04S4YdDarD0C&pg=PA356. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Peter Allan Lorge (2005). War, politics and society in early modern China, 900-1795. Taylor & Francis. p. 84. ISBN 0-415-31690-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=t203wZyNqIwC&pg=PA84. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ Tony Jaques (2007). Tony Jaques. ed. Dictionary of battles and sieges: a guide to 8,500 battles from antiquity through the twenty-first century, Volume 3. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1115. ISBN 0-313-33539-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=tW_eEVbVxpEC&pg=PA1115. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ History of Song

Bibliography[]

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

The original article can be found at Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty and the edit history here.