| Mladen Stojanović | |

|---|---|

| File:Mladen Stojanović.jpg | |

| Nickname | Doktor Mladen |

| Born | 7 April 1896 |

| Died | 1 April 1942 (aged 45) |

| Place of birth | Prijedor, Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Place of death | Jošavka, near Banja Luka, Yugoslavia |

| Buried at | Prijedor, Yugoslavia |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1941–42 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment |

| Battles/wars | Yugoslav Front of World War II |

| Awards | Order of the People's Hero (posthumously) |

| Spouse(s) | Mira Stojanović |

| Relations | Sreten Stojanović (brother) |

| Other work |

Physician Poet |

Mladen Stojanović (Serbian Cyrillic language: Младен Стојановић

- 7 April 1896 – 1 April 1942) was a Bosnian Serb physician who led the Yugoslav Partisans in the area of Kozara, north-western Bosnia, at the beginning of World War II. His father was a Serbian Orthodox priest in the town of Prijedor. At the age of fifteen, Stojanović became an activist of Young Bosnia, a youth revolutionary movement whose goal was to destroy Austria-Hungary. In 1912, Stojanović was inducted into Narodna Odbrana, an association founded in the Kingdom of Serbia aiming to organize a guerrilla resistance to the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary. In July 1914, Stojanović was arrested by the Austrian police and later sentenced to sixteen years' imprisonment, but he was pardoned in 1917. After World War I, he graduated from the medical faculty in Zagreb as a Doctor of Medicine, and in 1929, he opened his private practice in Prijedor. He established the tennis club of Prijedor in 1932. He reportedly became a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in September 1940.

After the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers and their creation of the Independent State of Croatia, Stojanović was imprisoned in June 1941 by the Ustaše—Croatian fascists who committed brutal crimes against the Serb population. Having escaped from the prison, Stojanović went to Mount Kozara, where he joined Communists who had earlier escaped from Prijedor. He was chosen by the Communist Party to lead the uprising in the district of Prijedor, part of the area of Kozara. The uprising began on 30 July 1941 without much control by Stojanović or any other Communists. The Serb villagers of the district who rose to arms, took control of a number of villages and threatened Prijedor, which was defended by German forces, Ustaše, and Croatian Home Guards. In August 1941, Stojanović was recognized as the principal leader of the insurgents in Kozara, who were then organized into Partisan military units. The Kozara Partisans began attacking the enemy at the end of September 1941, and by the end of that year, they had conducted about forty military actions. Stojanović participated in the planning and execution of all the major operations. At the beginning of November 1941, all Partisan units in Kozara were united into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment, and Stojanović was appointed its commander. By the end of 1941, most of the area of Kozara, covering about 2,500 square kilometres, was controlled by Stojanović's detachment.

On 30 December 1941, Stojanović arrived to the area of Grmeč, which was in the zone of responsibility of the 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment. The Italian troops operating in that area presented themselves as protectors of the Serbian people. Stojanović's tasks were to counter the Italian propaganda among the population, and to mobilise the Partisans of the 1st Krajina to fight against the Italians. He stayed in the area until mid-February 1942, and the Partisan leadership of Bosnia-Herzegovina estimated that he successfully accomplished his tasks there. At the end of February 1942, Stojanović was appointed chief of staff of the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina—a unified command of all Partisan forces in the regions of Bosanska Krajina and central Bosnia. A main task of the Operational Headquarters was to counter the rising influence of Chetniks in those regions. On 5 March 1942, Stojanović was severely wounded in an ambush by the Chetniks. He was transported to the field hospital in the village of Jošavka. Members of the Jošavka Partisan Company joined the Chetnik side on the night between 31 March and 1 April, when they took Stojanović prisoner. On the next night, a group of Chetniks carried him out of the house in which he lay recovering from his wound, and they murdered him. On 7 August 1942, Stojanović was proclaimed a People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

Biography[]

Early life[]

Stojanović's home town of Prijedor around 1910

The third child and the first son of Serbian Orthodox priest Simo Stojanović and his wife Jovanka, Mladen Stojanović was born in Prijedor on 7 April 1896. Bosnia and Herzegovina was at the time occupied by Austria-Hungary. The town of Prijedor was located in the province's north-western region, known as Bosanska Krajina.[1] Stojanović's father was the third generation of his family to serve as a Serbian Orthodox priest. He graduated from a theology faculty, becoming the first in the family to attain a higher level of education. He was active in the political struggle for ecclesiastical and educational autonomy of the Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Stojanović's maternal grandfather was a Serbian Orthodox priest from Dubica.[2]

Stojanović completed his elementary education at the Serbian Elementary School in Prijedor in 1906. He finished the first grade of his secondary education at the gymnasium in Sarajevo, before he entered the gymnasium in Tuzla in 1907, where he would finish the remaining seven grades. His brother Sreten Stojanović, who would become a prominent sculptor, joined him at the Tuzla gymnasium in 1908.[1]

Activist of Young Bosnia[]

Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina on 6 October 1908, which caused the so-called Annexation Crisis in Europe. The Kingdom of Serbia protested and mobilized its army, but on 31 March 1909, the Serbian government formally accepted the annexation.[3] In 1911, Mladen Stojanović became a member of the secret association of students of the Tuzla gymnasium.[4] The association was called Narodno Jedinstvo "National Unity", and its members described it as a youth society of nationalists. It was part of a youth revolutionary movement, later named Young Bosnia,[5] which had no central organization or written programme. The common goal of all groups in this movement was a revolutionary destruction of Austria-Hungary.[6] Achieving this goal should be followed by South Slavs uniting and creating a federal state with Bosnia-Herzegovina within it—as was the prevailing opinion in Young Bosnia. Its activists were Bosnian Serbs, Muslims, and Croats, though the Serbs were in majority.[7] The movement was initiated in 1904 by Serb students of the gymnasium in Mostar.[6] Young Bosnia's activists saw literature as indispensable to revolution, and most of them tried their hand at writing poems, short stories, or critiques.[8]

The gymnasium in Tuzla, which Stojanović attended from 1907 to 1914

Stojanović wrote poems,[9] and read the works of Petar Kočić, Aleksa Šantić, Vladislav Petković Dis, Sima Pandurović, Milan Rakić, and, later, the works of Russian authors.[10] In his final years at the gymnasium, he read Plato, Aristotle, Rousseau, Bakunin, Nietzsche, Jaurès, Le Bon, Ibsen, and Marinetti, among others.[11] Stojanović's secret association, National Unity, held meetings at which its members presented lectures they prepared from books they read. They also discussed current issues concerning the Serbian people in Bosnia-Herzegovina.[10] All members of the association were Serbs.[4] Generally, Stojanović's lectures were about educating people on practical issues of health and economy. During the summer break of 1911, Stojanović travelled across Bosanska Krajina lecturing in villages.[12] One of the aims of Young Bosnia was to eliminate the backwardness of their country.[6]

In the spring of 1912, Stojanović and his closest schoolmate Todor Ilić were inducted into Narodna Odbrana "National Defence",[4] an association founded in Serbia in December 1908 on the initiative of Branislav Nušić. The aims of this association included organizing a guerrilla resistance to the Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and spreading national propaganda. In a short time, National Defence established a network of local committees throughout Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Its members from the latter territory gathered intelligence on the Austrian army, and passed it to the Serbian secret service.[13]

Stojanović and Ilić travelled illegally to Serbia during the summer break of 1912, to receive a military training that National Defence organized for its members. They stayed for several days in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, where they met Gavrilo Princip, another activist of Young Bosnia who was also a member of National Defence. Stojanović and Ilić then spent a month at army barracks in Vranje, southern Serbia, participating in the military drills under the command of Vojin Popović, a famous Chetnik guerrilla fighter. Back in school, the two friends resumed their activities in National Unity. Its members decided that Muslims should also be drawn into the association. After Trifko Grabež was expelled from the Tuzla gymnasium for slapping a teacher during a quarrel, the association organized a strike in the school. Mostly Serb students participated in the strike, while it gained little support among the students of other ethnicities. The school then took disciplinary measures against Ilić and Stojanović, who were regarded as the main organizers of the strike. Ilić also lost his scholarship.[4]

In the autumn of 1913, Stojanović entered the eighth and final year of his secondary education. National Unity was visited that year by a group of activists of Young Bosnia who were university students in Prague, Vienna, and Switzerland. These activists held a series of lectures to the members of the association, explaining them the current political situation in the world, and promoting the unity of South Slavic peoples in their struggle to liberate themselves from Austria-Hungary. These lectures influenced Stojanović to firmly adopt a Yugoslavist stance. At the beginning of 1914, Ilić and Stojanović became, respectively, the president and the vice-president of National Unity. It then numbered 34 members, including four Muslims and four Croats.[14] At that time, National Unity was one of the most active groups of Young Bosnia.[15]

According to Vid Gaković, who was a member of National Unity in 1914, Stojanović was an ambitious and talented young man. He was determined that his voice be heard, and he liked being the centre of attention. He was severe to younger members of the association, whom he sometimes sharply criticised. Still, his bearing was not at all repulsive, and younger students liked being around him. Gaković described him as tall and handsome, and as one who greatly cared about his appearance; he wore a bow tie and a broad-brimmed hat.[16]

On the morning of 28 June 1914, in Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife.[17] Princip acted as one of a group of conspirators, which also included Trifko Grabež; the whole group was arrested by the Austrian police after the assassination.[18] Blaming Serbia for the attack, Austria-Hungary would declare war on that state a month later, which marked the beginning of World War I.[19] Shortly after the assassination, Stojanović wrote in his notebook a quote from Giuseppe Mazzini: "There is no more sacred thing in the world than the duty of a conspirator, who becomes an avenger of humanity and the apostle of permanent natural laws."[6] On 29 June, Stojanović took his final exams at the Tuzla gymnasium. Soon afterwards, he and Ilić wrote a draft of their manifesto to the South Slavic youth,[14] referring to Young Bosnia in a sentence:[5]

|

Зар не осјећате, синови једне Југославије, да у крви лежи наш живот и да је атентат бог богова Нације, јер он доказује да живи Млада Босна, да живи елеменат којег притишће несносни баласт империјалистички, елеменат који је готов да гине. |

|

One of the members of National Unity was Vojislav Vasiljević, a close friend of Princip's. The Austrian police searched his notebooks and found a list of all members of the association. Vasiljević kept evidence of the payment of membership fees.[5] All on the list, including Stojanović, were arrested on 3 July 1914.[14] They were soon joined by Stojanović's younger brother Sreten, who was arrested for his anti-Austrian revolutionary correspondence with Ilić.[16] Beside the conspirators who assassinated Franz Ferdinand, six more groups of activists of Young Bosnia were arrested.[5] The group containing the members of National Unity was called the Tuzla group. The criminal investigation against them began on 9 July, and it would last for more than a year.[14] They were first kept in a prison in Tuzla, and then in Banja Luka, and finally in Bihać. In the Banja Luka prison, the whole group was kept in the same room, which enabled them to organize political and literary discussions. They issued a comic and satirical magazine, called Mala paprika [Little Paprika], the copies of which they made using carbon paper. A number of copies found their way out of the prison.[16]

In the Bihać prison, the Tuzla group created a literary magazine named Almanah [Almanac]. For its first and only issue, Stojanović wrote several poems and an essay. Its editor-in-chief was Ilić, while Sreten Stojanović and Kosta Hakman contributed to it with their illustrations. The Stojanović brothers and Ilić also learned French during their incarceration.[16] The trial against the Tuzla group was held between 13 and 30 September 1915 in Bihać. Ilić was sentenced to death, Stojanović to sixteen years' imprisonment, while the other members of the group received between ten months and fifteen years.[5] Especially aggravating for Ilić and Stojanović was their participation in the military drills in Serbia. This became known to the Austrians at the beginning of World War I, when their army temporarily took Loznica in western Serbia. There they found documents of National Defence containing records of all Bosnian attendees of the drills.[14]

Stojanović and others of the group were sent to the prison in Zenica. Three months after the sentence, they were joined by Ilić, whose death penalty was commuted to 20 years' imprisonment. In the Zenica prison, each convict had to spend the first three months in a solitary confinement. This turned out to be very hard for Stojanović, who became mentally unwell. He grew so emaciated that Ilić hardly recognized him. Stojanović later recovered and took a course in shoemaking, which was given in the prison. Afterwards, he fell seriously ill and had to undergo a surgery in the prison hospital.[20] In the autumn of 1917, the Austrian authorities pardoned all convicts of the Tuzla group, except Ilić. Stojanović went to his family in Prijedor. On a medical examination, he was declared unfit for army service due to his surgery, so he was not drafted into the Austrian army and sent to a front. He entered the School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, shortly before the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, which took place in November 1918. He participated in the disarming of Austrian troops in Sremska Mitrovica.[20]

Interwar period[]

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was created on 1 December 1918, and Bosnia-Herzegovina became part of it. Stojanović continued studying medicine in Zagreb. As a former activist of Young Bosnia, he was offered a King's scholarship, but he refused it. In Zagreb, he reunited with his former schoolmate Nikola Nikolić, who had also been a member of National Unity. After the release from the Zenica prison, Nikolić was drafted into the Austrian army and sent to the Russian front. There he surrendered to the Russians and participated in the October Revolution. Nikolić's account of the revolution influenced Stojanović to adopt a more leftist stance. In this period, Stojanović's favourite authors were Maksim Gorky and Miroslav Krleža. His professor of anatomy, Drago Perović, arranged for him to visit an anatomical institute in Vienna. Stojanović went there several times in 1921 and 1922. He befriended members of a leftist association of Yugoslav students of the Vienna University.[21] When this association held a protest against the king and government of Yugoslavia, Stojanović took part in it and delivered a speech. Behind the protest stood the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.[22]

Stojanović graduated from the medical faculty as a Doctor of Medicine in 1926, and he worked for two years as a trainee physician in Zagreb and Sarajevo. He then opened his private practise in Pučišća on the Adriatic island of Brač. In 1929, he returned to his home town of Prijedor, where he opened his practice on the first floor of the Stojanović family house.[23] His mother had lived alone in the house since his father's death in 1926.[24] Stojanović soon became a popular figure in the area of Prijedor. His patients asserted that just talking with him was by itself curative. He treated poor people for free; he once sent a homeless man to a hospital in Zagreb and paid for the man's surgery there.[23] Stojanović earned well and lived at a rather high standard.[25] People from other areas of Bosanska Krajina were also coming to him for a medical treatment. In villages of the district of Prijedor, where brawls were not uncommon, rowdies sang about him:[23]

Udri baja nek palija ječi, |

Hit [me], buddy, let the club resound, |

In 1931, Stojanović was contracted with the Prijedor branch of the state railway company to provide health care for its employees.[26] In 1936, he was contracted with the iron ore mining company in Ljubija, a townlet near Prijedor. He would visit the mining company's clinic twice a week.[27] He also taught hygiene at the gymnasium in Prijedor.[28] Together with other intellectuals from this town, he gave lectures to the miners at the their club in Ljubija. In his lectures, usually on medical issues, he also described the economic and social position of workers in more advanced countries. He socialized with the miners, and treated their family members for free.[27] He was very active socially, and participated in sports. He established the tennis club of Prijedor in 1932;[23] he once bought new kit for all players of the football club Rudar Ljubija.[29] His contracts with the railway company and the mining company were both terminated in 1939. This caused a protest of the railway employees in Prijedor, and Stojanović's contract with that company was renewed.[26]

The Ljubija miners were on strike between 2 August and 8 September 1940.[27] Some of the leaders of the strike were members of the secret Communist cell in Ljubija, which was formed in January 1940. The Communist Party had been outlawed in Yugoslavia since 1921. The Communist organization of Banja Luka sent its experienced member Branko Babič to help the strike leaders.[30] According to Babič, a Communist from Prijedor introduced him to Stojanović at the beginning of September 1940. Babič then stayed for several days at the doctor's house, conducting the strike. Seeing Stojanović as a Communist sympathizer, Babič proposed to him to join the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Stojanović at first declined, saying that he still had bourgeois habits, though he had read much of the Marxist literature. After further conversations with Babič, Stojanović agreed to become a member of the party.[25]

At the end of September 1940, Babič and all five members of the Ljubija cell held a meeting at which they unanimously decided to admit Stojanović into the Communist Party. When Babič informed Stojanović of the decision, the doctor reportedly declared that he had felt like a Communist since 1922. As an activist of Young Bosnia, he believed that the destruction of Austria-Hungary would bring freedom to the South Slavs, but the Kingdom of Yugoslavia disappointed him sorely soon after its creation. He then saw that the struggle for the people's writes and dignity had to go on.[30] Babič held Stojanović in high esteem, and regarded him as ardently devoted to the Communist cause.[25] Some Communists, however, continued to refer to Stojanović as a Communist sympathizer,[31] and some regarded him as a "salon Communist".[25]

Onset of World War II[]

Partition of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers

On 6 April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded from all sides by the Axis powers, primarily by Nazi German forces.[32] Stojanović was assigned as a physician to an infantry battalion based in Banja Luka. During the invasion, this battalion moved for several days toward Dalmatia, before it completely disintegrated without firing a bullet at the enemy. That was the end of the April War for Stojanović, and he returned to Prijedor.[33] The invasion ended with the capitulation of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April, and the Axis powers then proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Almost all of modern-day Croatia, all of modern-day Bosnia-Herzegovina, and parts of modern-day Serbia were combined into the Independent State of Croatia (often called the NDH, from the Croatian language: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska ).[32] It was a puppet state described as an "Italian-German quasi-protectorate",[34] which was under the brutal regime of the Ustaše, Croatian fascists. The organizer of the Ustaše, Ante Pavelić, headed the government of the NDH. Its objective was to eliminate the ethnic Serb population through mass killings and forced assimilation, and many Serbs fled from the NDH to the German-occupied part of Serbia.[32]

The NDH's repressive measures also included taking prominent Serbs as hostages to be executed in case of a Serb attack against the Ustaše or Germans. To avoid being taken hostage, Stojanović paid 100,000 dinars to the Ustaše in Prijedor.[33] Resistance movements began emerging in the occupied Yugoslavia. Yugoslav royalists and Serbian nationalists under the leadership of then-Colonel Draža Mihailović founded the Ravna Gora Movement, whose members were called Chetniks. Their sporadic forays on the German occupiers began in May 1941.[35][36] The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY), led by Josip Broz Tito, made preparations to rise to arms at a favourable moment.[37] In the view of the Communists, the fight against the Axis and its domestic collaborators was to be a common fight of all Yugoslav peoples.[38]

Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, began on 22 June 1941.[39] On the same day, the Ustaše began arresting Communists and their known sympathizers in the towns of Bosanska Krajina, including Prijedor. As this was predicted by the Communists, most of them avoided capture by escaping to the villages or hiding in the towns. One of the few Communists who were arrested in Prijedor was Stojanović.[40] He was added to the hostages who were imprisoned on the second floor of a school in the town. They were subject to forced labour, being led each morning through the town to repair the road to Kozarac. The column of the hostages was usually headed by Stojanović carrying a shovel on his shoulder.[33] The Croatian Home Guards guarding the prison treated the doctor well. While detained, Stojanović lectured Marxism to a group of hostages.[41]

Flag of the Yugoslav Partisans

On the day of the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, the Executive Committee of the Communist International, head-quartered in Moscow, telegraphed the Central Committee of the CPY to take all measures to support and alleviate the struggle of the Soviet people, and to organize partisan detachments to fight the Axis in Yugoslavia. The Executive Committee stressed that the fight, at the current stage, should not be about socialist revolution, but about the liberation from the Axis occupiers.[39] On 27 June 1941, in Belgrade, the Central Committee of the CPY established the Chief Headquarters of the National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia, under the supreme command of Tito. On 4 July, the Central Committee decided to launch the nation-wide armed uprising. This marked the beginning of the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia, whose members were called Partisans.[42] On 13 July, in Sarajevo, the CPY Provincial Committee for Bosnia-Herzegovina, headed by Svetozar Vukmanović, organized the province into four military regions: Bosanska Krajina, Herzegovina, Tuzla, and Sarajevo.[43][44]

The Prijedor Communists were keen to rescue Stojanović from his imprisonment, but their attempts to bribe Ustaše into releasing him, failed. They also considered storming the school in which he was kept.[41] On 17 July, just after midnight, Stojanović asked a guard to let him go to the toilet, which was located on the first floor of the school. The guard let him go and followed closely behind him. When they were half way down the stairs, Stojanović shouted "Fire!" as smoke came from a room on the second floor. During the commotion of the guards and hostages extinguishing the fire, Stojanović entered the toilet, through whose window he escaped out of the school.[45] He went to the village of Orlovci several kilometres from Prijedor, where he was accompanied by Rade Bašić, a young Communist who had earlier escaped from the town. Bašić escorted Stojanović toward Mount Kozara,[41] which rises north of the Prijedor Plain reaching the altitude of 978 metres.[46]

Yugoslav Partisan[]

Area of Kozara[]

July–August 1941[]

Mount Kozara, near the site of the first Partisan camp in the area

On the morning of 19 July 1941, Stojanović and Bašić arrived at the camp of the Communists and their sympathizers who escaped from Prijedor. The camp was situated at the locality called Rajlića Kosa, above the village of Malo Palančište.[45] The news of Stojanović's escape soon spread throughout the district of Prijedor. Now that a well-known and respected doctor joined the men in the camp, most of whom were in their early twenties, this whole group gained in credibility and esteem.[40] People from surrounding Serb villages, coming in groups, brought food and other useful stuff to Stojanović and his young comrades. Stojanović held speeches to the villagers, telling them to be prepared for an uprising soon. He urged them to bring him rifles they were hiding at their homes.[45] The camp at Rajlića Kosa was the first Partisan camp in the area of Kozara.[47]

This area, located in northern Bosanska Krajina and centred around Mount Kozara, covers about 2500 square kilometres. In 1941 the area had a population of nearly 200,000 people, mostly Serbs, who predominated in the villages. The towns in the area, the biggest of which was Prijedor, had a mixed Bosnian Muslim, Serb, and Croat population. Several villages were inhabited by ethnic Germans or Volksdeutsche. The economy of Kozara was dominated by agriculture, but there were also about 6000 workers, employed in a coal mine and several plants. The first Communist cells in the area were established shortly before the Axis invasion, mostly in the towns. Kozara had seen four uprisings against the Ottomans during the 19th century.[46]

On the night between 25 and 26 July 1941, at Orlovci, Stojanović and seven other leading Communists of Kozara had a meeting with Đuro Pucar, the head of the CPY Regional Committee for Bosanska Krajina. Pucar told the assembled Communists that military actions against the enemy should start as soon as possible. The actions should be of a guerrilla type, for which purpose partisan detachments should be formed in the area. Stojanović and Osman Karabegović were appointed to lead the uprising in the district of Prijedor.[48] On 27 July, in western Bosanska Krajina, Partisans took the town of Drvar and thus marked the beginning of the uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina. At that time, the insurgents in Kozara were still not organized into military units.[48] In the district of Prijedor, Stojanović and Karabegović had little control over the men from the district's villages who rose to arms.[45] Pucar referred to the district's insurgents as the "Prijedor Company", the bulk of which was composed of the villagers, numbering several hundred men.[49] Many of them had no firearms.[45]

According to Pucar, the "Prijedor Company" was planned to attack Ljubija.[49] On 30 July, however, the insurgents attacked Palančište and rescued fifteen hostages whom Ustaše held in that village. This was carried out contrary to Stojanović's direct order not to attack Palančište.[48] The insurgents then advanced toward Prijedor and developed a front-line facing the town, which was defended by Croatian Home Guards, Ustaše, and German forces. The front-line stabilized after three days of fighting, leaving the "Prijedor Company" in control of seven villages.[49] The railway traffic between Ljubija and Zagreb was disrupted, which stopped the export of iron ore from Ljubija to Germany. Beside the district of Prijedor, the uprising in Kozara also involved the districts of Dubica and Novi. By mid-August, five detachments of Partisans were formed within the territory held by the Kozara insurgents. These detachments, including the Prijedor Detachment commanded by Stojanović, together kept a front-line facing Kozarac, Prijedor, Lješljani, Dobrljin, Kostajnica, and Dubica.[50]

The leaders of the uprising in Kozara assembled on 15 August 1941 in the village of Knežica to confer on the current situation in the area. At the conference, Stojanović was recognized as the principal leader in Kozara; this recognition mostly resulted from his pre-war social status and high repute among the people. It was concluded that making the front-line was a mistake, as the Partisans should rather be oriented toward guerrilla warfare.[51] At some point during the conference, Stojanović stressed the importance of binding as many enemy troops to the area as possible, so that they could not be sent to the Russian front to fight against the Red Army.[52] As the five detachments in the area were bound to their specific territories, it was decided that yet another detachment should be formed, which could operate anywhere in Kozara. Stojanović and Karabegović were chosen to be, respectively, the commander and the political commissar of that detachment, called the Kozara Detachment. This unit was promptly formed, numbering about forty men. With a red banner at its head, the Kozara Detachment paraded for a couple of days through villages in the Partisan-held territory. The villagers would gather, and Stojanović would hold speeches to them.[51]

Croatian Home Guards, Ustaše, and a German battalion from Banja Luka, about 10,000 soldiers altogether, attacked on 18 August 1941 the Partisan-held territory in Kozara. The enemy troops broke the front-line of the Partisans, and penetrated the territory. There they burned houses and looted cattle and grain in the villages.[50] Some of the villagers became demoralized, and they blamed Partisans for their losses; some placed white flags on their houses. The Partisan units retreated deeper into the mountain, to its forested areas. Stojanović led the Kozara Detachment toward Lisina, the highest peak of Kozara. In the evening, he assembled his men in line. He explained them that they were in the army of the Communist Party and all peoples of Yugoslavia, so they could not allow themselves to be attached to any specific village or area. He advised those who could not detach themselves from their homes, to lay down their weapons and leave. Several men thus left the detachment, which then proceeded toward Lisina. There they organized a camp, and spent some time in military training and political indoctrination.[52] The attack of 18 August was the first counter-insurgency operation in Kozara, and the Partisans emerged from it without significant losses.[50]

September–December 1941[]

Lisina, the highest peak of Kozara

The leaders of the uprising in Kozara assembled again on 10 September 1941, below Lisina. The five detachments of the Kozara Partisans were rearranged into three companies,[53] possessing 217 rifles altogether. At the end of September, the Kozara Partisans began attacking the enemy in the area. At first they attacked only its weaker forces, but soon they directed their actions against its stronger forces too. They gradually accumulated military experience, and obtained more weapons and ammunition by taking them from the enemy. More men joined the Partisans, and two more companies were formed in Kozara by the end of October. The Partisans gained control over a number of villages in the area.[54] After a general reorganization of the Yugoslav Partisan units, those in Kozara were united into the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment, which was established at the beginning of November 1941. Stojanović was appointed commander of this major detachment.[55] By mid-November, Stojanović's detachment had 670 men organized in six companies and armed with 510 rifles, 5 light machine guns, and 1 heavy machine gun.[54]

Between the end of September and the end of December 1941, the Kozara Partisans performed around forty military actions against the enemy. Stojanović participated in the preparation and performance of all bigger actions, most notable of which are the battles of Podgradci, Mrakovica, and Turjak. Regarding Podgradci, Stojanović argued that this village should be taken for two reasons: it was situated deep within Kozara, and from it, the enemy could easily disrupt the advance of the Partisans toward other villages of the district of Gradiška; and there was a sawmill in Podgradci, which worked for the Ustaše and Germans.[56] On 23 October 1941, Partisans under Stojanović's command took Podgradci after five hours of fighting.[54] The sawmill and its stored products were burned down. Among these products was a large quantity of rail-road ties, which the Germans allegedly planned for the repair of rail roads that the Soviet partisans destroyed in the occupied Ukraine. Stojanović therefore saw this action as a symbolic collaboration with the Red Army. A number of Ustaše and Croatian Home Guards were captured in Podgradci. The Ustaše were promptly executed. The Home Guards were given a speech by Stojanović, before the Partisans gave them to eat and escorted them to the Una River, across which they were boated to Croatia.[56]

The third counter-insurgency operation in Kozara was undertaken at the end of November 1941 by about 19,000 Croatian Home Guards, Ustaše, and Germans.[57] The Partisans emerged from the operation without significant losses, though the NDH's propaganda claimed that the "rebels" in Kozara were destroyed and that Stojanović was killed.[58] The Partisans never repeated the mistake of frontal resistance.[54] When stronger enemy forces advanced toward them, the Partisan units manoeuvred so as to position themselves behind the attackers, thus avoiding the fights which they could not win. The Partisans therefore did not defend villages. Hundreds of Serb civilians were killed in the villages by the Ustaše and Germans during the third counter-insurgency operation. This led to a loss of support for the Partisans among the population. Stojanović regarded that a significant victory over the enemy would be the best way to restore the lost support.[58]

After the third counter-insurgency operation, a battalion of the Croatian Home Guard was stationed at Mrakovica, a peak of Kozara.[57] By Stojanović's order, this battalion was attacked by five companies of the 2nd Krajina Detachment on 5 December 1941 at 5:30 am. The battle ended by 9:30 am with a smashing victory of the Partisans.[59] They lost five men, while 78 Home Guards were killed, and around 200 were captured. The Partisans also seized 155 rifles, 12 light and 6 heavy machine guns, 4 mortars, 120 mortar rounds, and 19000 cartridges.[57] The last action of the 2nd Krajina Detachment under Stojanović's command was the battle of Turjak.[60] Four companies of the detachment attacked and took this village on 16 December 1941. The Partisans captured 134 Home Guards;[61] letters found with them, which they wrote to their families, revealed their extremely low morale. The capture of Turjak opened up the district of Gradiška to the Kozara Partisans. The Home Guards retreated from Podgradci without much fighting. Soon a great part of the district was under Partisan control. In this way, Stojanović's detachment controlled most of Mount Kozara, as well as the rolling region around it, known as Potkozarje.[60]

More and more men joined Stojanović's detachment, and at the end of 1941, it had over one thousand well armed soldiers organized in three battalions of three companies each.[60] The detachment established good relations with the Muslim population of the area; a number of Muslims from Kozarac joined the ranks of the Partisans.[62] On 21 December, at Lisina, Pucar held a meeting with Communists of Kozara. At the meeting, Stojanović presented a short history of the uprising in Kozara.[60] Pucar then stated that the 2nd Krajina was the best organized detachment in Bosanska Krajina, in the military, political, financial, and all other respects.[63]

On 24 December, the Banja Luka headquarters of the Croatian Home Guard offered a reward for Stojanović. A document of the headquarters described Stojanović as the most intelligent and dangerous rebel leader, who planned and carried out attacks in a highly systematic manner. The headquarters was especially concerned about Stojanović's treatment of the captured Croatian soldiers—his giving them a Communist propaganda speech, offering them food and cigarettes, dressing their wounds, and then letting them go home. According to the headquarters, Stojanović and his men thus exerted such an influence on the morale of the soldiers as to make them useless in future fights with the Partisans.[63] The courage and fighting spirit of the Kozara Partisans became famous in Bosanska Krajina, but also in other parts of Bosnia and in the areas of Croatia bordering on Bosnia.[57] In the villages of Kozara, people sang about Stojanović:[60]

Ide Mladen vodi partizane |

There goes Mladen, leading the Partisans |

Area of Grmeč[]

On 29 or 30 December 1941, Stojanović arrived to the area of Grmeč, which was in the zone of responsibility of the 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment.[64] This zone, located in western Bosanska Krajina, also contained the area of Drvar, where the uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina began. The military activities of the Partisans in those areas had become diminished since the capture of Drvar by Italian troops on 25 September 1941. The Italians spread their propaganda, presenting themselves as protectors of the Serbian people against the Ustaše, and in fact providing this protection.[62] There were groups of Serbs who collaborated with the Italians. According to Karabegović, the Partisans of the 1st Krajina became more active after Pucar held a conference with their commanders on 15 December 1941, but this activity was still weak in northern parts of the area of Grmeč. Stojanović came there to counter the Italian propaganda, and to mobilise the Partisans to fight against the Italians and their collaborators;[62] he was accompanied by Karabegović.[64]

Serbian epic hero Miloš Obilić, with whom Stojanović was compared by villagers in Grmeč

According to writer Branko Ćopić, who was a Partisan in the area of Grmeč, Stojanović was greeted by a mass of villagers when he crossed the Sana River and entered the area. They welcomed him with the traditional bread and salt ceremony. Prominent villagers shook hands with him, and they compared him with Miloš Obilić, a famous Serbian epic hero from the medieval Battle of Kosovo. When several women approached him to kiss his hands, he gently declined this mark of respect, saying that he was not a priest, but a Communist.[65]

Stojanović travelled throughout the area, visiting the villages and inspecting individual companies and platoons of the 1st Krajina. His visits were accompanied by parades of the Partisan units, and by mass gatherings of people, including youth and children. At the gatherings, Partisan songs were sung, slogans were shouted, and banners were waved. Stojanović held speeches to the villagers and soldiers. He emphasised that the Italian troops present in the area were not protectors of the Serbs, but occupiers and enemies. He branded those who collaborated with the Italians, as traitors to the Serbian people.[64][66] Stojanović's speeches were not well received by some persons. They spread rumours that he was not Mladen Stojanović, but a "Turk" (Muslim) who just looked like him. According to them, Stojanović had been killed by Ustaše in August 1941, and his impostor was engaged by the Communists to deceive the people. Hardly anyone gave credence to these rumours.[65]

On 22 January 1942, at the headquarters of the 1st Krajina in the village of Majkić Japra, Stojanović presided over a conference of the commanding staff of the detachment and the political activists of the area of Grmeč. He criticised the headquarters of the detachment, enumerating the flaws he found in it, such as: there was no division of functions and no personal accountability among its members; the headquarters had no communication with the companies of the detachment, and it did not act as a military-political leadership; and there were no designated couriers at the constant disposal of the headquarters. Stojanović was generally pleased with the Grmeč Partisans, describing them as courageous, enthusiastic, firm, and trustworthy, though somewhat raw. However, he noted that the platoons of the detachment were dispersed in villages, and had no contacts with each other. In this way, according to Stojanović, the Partisans were losing their soldierly characteristics, and becoming more like peasants. Stojanović criticized the opinion, present among some of the Partisans, that the political commissars should be abolished. He warned that the Partisans who wore emblems other than the red star, would be punished for indiscipline.[67]

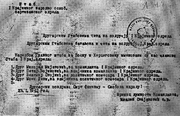

Document dated 23 January 1942 in which Stojanović informs the companies of the 1st Krajina about the appointment of Milorad Mijatović as commander of the detachment

At the conference, Stojanović installed Milorad Mijatović, a Partisan from Kozara, as the new commander of the 1st Krajina. He also installed Petar Vojnović as deputy commander, while Velimir Stojnić and Salamon "Moni" Levi remained in their capacities as commissar and deputy commissar, respectively.[67] Levi was an acquaintance of Stojanović's from his visits to Vienna in 1921 and 1922.[68] During his sojourn in the area of Grmeč, Stojanović met young writer Branko Ćopić, whom he encouraged to write the fight of the Partisans into poetry. Stojanović regarded that poetry was much more acceptable for the Partisans than prose. "Poetry and revolution always go hand in hand," said Stojanović.[65] He stayed in the area until mid-February 1942.[69] The Partisan leadership of Bosnia-Herzegovina estimated that Stojanović was successful in countering the Italian propaganda and improving the condition of the 1st Krajina Detachment.[62]

North-west central Bosnia[]

Stojanović left the area of Grmeč and went to Skender Vakuf in north-west central Bosnia to participate in the first regional conference of Communists of Bosanska Krajina,[65] which was held from 21 to 23 February 1942.[70] In the Partisan terminology, the military-political region of Bosanska Krajina also included central Bosnia.[43] At the Skender Vakuf conference, presided by Pucar, Stojanović, and Karabegović,[71] the participants analysed the military and political situation in the region. A big problem for the Communists was the increase of Chetnik influence, which was strongest in south-eastern Bosanska Krajina and the adjacent north-west central Bosnia, in the zones of responsibility of the 3rd and 4th Krajina Detachments. A number of Partisans of these detachments joined the Chetnik side.[72][73] Only in the area of Kozara was Chetnik influence thwarted in its inception.[54][62] At the conference, Stojanović was appointed commander of a unified command of the Partisan forces in Bosanska Krajina,[70] but on 24 February, he was replaced with Kosta Nađ.[74][75] The unified command was named as the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina,[76] and Stojanović became its chief of staff,[72][77] as well as its deputy commander.[78]

According to Nađ, the split between the Partisans and the Chetniks in Bosanska Krajina and central Bosnia, had begun on 14 December 1941 in the village of Javorani: Lazar Tešanović, the schoolteacher in Javorani, influenced members of the local Partisan unit to join the Chetnik side.[79] Tešanović then organized a Chetnik unit of about 70 to 80 men,[73] and at the beginning of March 1942, he and his men were in the village of Lipovac. On 5 March, Stojanović, Nađ, and Danko Mitrov, the commander of the 4th Krajina, set out for Lipovac with the Kozara Proletarian Company,[75] an assault unit formed in February 1942.[80] According to some sources, the Partisans went to Lipovac for prearranged negotiations with Tešanović,[72] while other sources state that they intended to disarm Tešanović and his Chetniks.[75] When the column of the Partisans approached the school in Lipovac, they were showered with bullets by the Chetniks. Stojanović was severely wounded in the forehead.[81] The Partisans remained pinned down by the enemy fire until evening; thirteen of them were killed and eight were wounded, beside Stojanović. At the nightfall, he and the other wounded were transported to the Partisan field hospital in the village of Jošavka.[75]

For about ten days Stojanović lay in the field hospital, before he was moved to a house some 700 to 800 metres away.[81] At the end of March 1942, the Operational Headquarters for Bosanska Krajina and the headquarters of the 4th Krajina were both located in Jošavka. The two headquarters and the field hospital were attacked on the night between 31 March and 1 April by members of the Jošavka Partisan Company. They joined the Chetnik side under the influence and leadership of Radoslav "Rade" Radić, the deputy commissar of the 4th Krajina. That night the Chetniks killed 15 Partisans in Jošavka.[73][82] According to Danica Perović, the physician who attended Stojanović, the Chetniks posted a watch before the house in which he lay, after they seized his firearms. Through a messenger, Radić told Stojanović to write a letter in which he would order Danko Mitrov to remove all Partisan units from the area around Jošavka. Stojanović, however, wrote a letter in which he encouraged Mitrov to keep on the Partisan fight. Next night, a group of Chetniks came to Stojanović and placed him on a blanket, with which they carried him out of the house. When they approached a nearby stream, one of them fired two shots at Stojanović and killed him.[81]

On 2 April, villagers of Jošavka buried Stojanović on a steep, wooded hillside.[80] By the end of April 1942, most of the companies of the 4th Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment joined the Chetnik side or disintegrated.[83] Rade Radić became the commander of the Chetnik detachments in Bosnia. After the war, he was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of Yugoslavia; he was executed by firing squad in 1945.[72] Stojanović's remains were transported to Prijedor in November 1961.[84]

Legacy[]

Mladen Stojanović park in Banja Luka.

On 19 April 1942, the headquarters of the 2nd Krajina decided to rename the detachment as the 2nd Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment "Mladen Stojanović". The Kozara Partisans vowed to avenge his death on all the "enemies of the people". The 2nd Krajina and four companies of the 1st Krajina liberated Prijedor on 16 May 1942.[85] On 7 August 1942, the supreme headquarters of the Yugoslav Partisans proclaimed Stojanović a People's Hero of Yugoslavia. After World War Two, a monument to him was erected in Prijedor, a work of his brother Sreten. Streets, firms, schools, hospitals, pharmacies, and associations were named after him in cities, towns, and villages throughout the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Many songs were composed about Stojanović, celebrating him as a hero.[84]

Each year in April, Stojanović is ceremonially commemorated in Prijedor, with wreaths being laid at his monument. At the 2012 commemoration, the president of the Partisan War Veterans' Association of Republika Srpska declared:[86]

|

Mladen je bio čovjek za primjer, revolucionar od najranije mladosti pa do kraja života, najpopularnija ličnost ustanka na Kozari, Krajini i mnogo šire i jedan od najhrabrijih boraca i rukovodilaca Narodnooslobodilačke borbe. Zato je njegov je lik ostao da živi u sjećanju zajedno sa slavom herojske Kozare. |

|

Poetry[]

In his youth, Stojanović wrote poems, but he published only one of them, in the literary magazine Književni jug,[9] in its issue of 16 September 1918;[87] an editor of Književni jug was Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić. A number of Stojanović's poems are preserved in a notebook that belonged to his closest schoolmate Todor Ilić. According to poet Dragan Kolundžija, Stojanović's poems are lyrical miniatures composed in free verse, focused on man and nature, and filled with melancholy. Kolundžija finds that what inspired Stojanović to write poetry is reflected in his verse Krvav je bol "Bloody is pain".[9] According to poet Miroslav Feldman, who first met Stojanović in 1919 in Zagreb, his poems were sad and permeated with a yearning for a brighter, more joyous life.[22]

Stojanović wrote an essay which is published as the foreword to a 1920 book of poetry by Feldman, titled Iza Sunca [Behind the Sun]. In 1925, Stojanović initiated the creation of an anthology of Yugoslav lyric poetry. On this project, he worked together with Feldman and Gustav Krklec. The three poets completed the anthology, but for an unclear reason it was never published.[88]

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 9–12

- ↑ Adamović 2010, para. 2–5

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, p. 626

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bašić 1969, pp. 20–25

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Dedijer 1966, pp. 580–83

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Dedijer 1966, pp. 293–98

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, p. 353

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, pp. 386–88

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bašić 1969, pp. 180–82

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Calic 2010, p. 64

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 26–30

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, pp. 636–39

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Bašić 1969, pp. 36–40

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, p. 512

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Bašić 1969, pp. 49–52

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, p. 593

- ↑ Dedijer 1966, pp. 35–37

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 61–65

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 87–89

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 101–2

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Bašić 1969, pp. 107–12

- ↑ Adamović 2010, para. 6

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Bašić 1969, pp. 93–95

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 115–18

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Bašić 1969, pp. 67–74

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 13

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 82

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 76–80

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 7

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Vucinich 1949, pp. 355–358

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Bašić 1969, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 272

- ↑ Vucinich 1949, pp. 362–365

- ↑ Roberts 1987, pp. 20–22, 26

- ↑ Roberts 1987, p. 23

- ↑ Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, p. 157

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, p. 152

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Marjanović 1980, pp. 85–87

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Bašić 1969, pp. 53–57

- ↑ Terzić 1957, pp. 41–44

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Anić, Joksimović, & Gutić 1982, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, p. 179

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Bašić 1969, pp. 17–20

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 9–15

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 66

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Marjanović 1980, pp. 89–93

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Vukmanović 1982, v. 1, pp. 211–214

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Karasijević 1980, pp. 134–36

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Marjanović 1980, pp. 94–95

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 32–35

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 42

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 Terzić 1957, pp. 136–38

- ↑ Terzić 1957, pp. 134–35

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 84–86

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Karasijević 1980, pp. 137–39

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 96–100

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 120–21

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Bašić 1969, pp. 122–27

- ↑ Karasijević 1980, p. 140

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 Vukmanović 1982, v. 2, pp. 150–54

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 129–30

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Bokan 1988, pp. 299–303

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Bašić 1969, pp. 136–40

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 131–35

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Bokan 1988, pp. 305–307

- ↑ Bašić 1969, p. 92

- ↑ Bokan 1988, p. 329

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Vukmanović 1982, v. 2, p. 36

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 141–42

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Samardžija, pp. 7–9

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Trikić & Rapajić, pp. 22–25 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "tri22" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Bokan 1988, p. 332

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Trikić & Rapajić, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Anić, Joksimović, & Gutić 1982, p. 101

- ↑ Hoare 2006, p. 257

- ↑ Trikić & Rapajić, pp. 51–52

- ↑ Nađ 1979, pp. 85–86

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Trikić & Rapajić, p. 27

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Bašić 1969, pp. 163–171

- ↑ Hoare 2006, p. 261

- ↑ Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 91–92

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Bašić 1969, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Borojević, Samardžija, & Bašić 1973, pp. 22–23

- ↑ "Pavić – Ideale heroja Mladena Stojanovića prenijeti na omladinu" (in Serbian). Pavić – The Ideals of the Hero Mladen Stojanović to Be Passed on to the Youth. City of Prijedor. 2 April 2012. http://www.gradprijedor.com/drustvo/pavic-ideale-heroja-mladena-stojanovica-prenijeti-na-omladinu.

- ↑ Stojanović 1918, p. 222

- ↑ Bašić 1969, pp. 103–6

References[]

- Adamović, Vedrana (2010). "O porodici Stojanović" (in Serbian). On the Stojanović Family. Museum of Kozara, Prijedor. http://www.muzejkozareprijedor.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=80:o-porodici-stojanovi&catid=63:o-porodici-stojanovi&Itemid=74.

- Anić, Nikola; Joksimović, Sekula; Gutić, Mirko (1982). "Narodnooslobodilačka vojska Jugoslavije" (in Serbian). National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia. Vojnoistorijski institut. http://books.google.com/books?id=xTErAAAAMAAJ.

- Bašić, Rade (1969). "Doktor Mladen" (in Serbian). Doctor Mladen. Narodna armija. http://books.google.com/books?id=EvWPAAAAIAAJ.

- Bokan, Branko J. (1988). "Prvi krajiški narodnooslobodilački partizanski odred" (in Serbian). The 1st Krajina National Liberation Partisan Detachment. Vojnoizdavački i novinski centar. http://books.google.com/books?id=7AkMHQAACAAJ.

- Borojević, Ljubomir; Samardžija, Dušan; Bašić, Rade (1973). "Peta kozaračka brigada" (in Serbian). The 5th Kozara Brigade. Narodna knjiga.

- Calic, Marie-Janine (2010). "Geschichte Jugoslawiens im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert" (in German). History of Yugoslavia in the 20th Century. C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-60645-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=cTjtGDNaViMC.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). "Сарајево 1914" (in Serbian). Sarajevo 1914. Prosveta. http://books.google.com/books?id=nYDRAAAAMAAJ.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2006). "Genocide and Resistance in Hitler's Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941–1943". New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726380-8.

- Karasijević, Drago (1980). "Kozara u Narodnooslobodilačkoj borbi i socijalističkoj revoluciji (1941-1945)" (in Serbian). Kozara in the National Liberation War and Socialist Revolution (1941-1945). Nacionalni park „Kozara“. OCLC 10076276.

- Marjanović, Joco (1980). "Kozara u Narodnooslobodilačkoj borbi i socijalističkoj revoluciji (1941-1945)" (in Serbian). Kozara in the National Liberation War and Socialist Revolution (1941-1945). Nacionalni park „Kozara“. OCLC 10076276.

- Nađ, Kosta (1979). "Ratne uspomene: Četrdesetdruga". In Jovo Popović (in Serbian). War Memories: 1942. Centar za kulturnu djelatnost Saveza socijalističke omladine Jugoslavije. http://books.google.com/books?id=KzuBAAAAIAAJ.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1987). "Tito, Mihailovic and the Allies,1941-1945". Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0773-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=43CbLU8FgFsC.

- Samardžija, Dušan D. (1987). "Jedanaesta krajiška NOU divizija" (in Serbian). The 11th Krajina National Liberation Assault Division. Vojnoizdavački i novinski centar. http://books.google.com/books?id=Cnt0mgEACAAJ.

- Stojanović, Mladen (1918). "Болни Дојчин" (in Serbian). The Ailing Dojčin. Niko Bartulović. http://scc.digital.bkp.nb.rs/view/P-0261-1918&p=393.

- Terzić, Velimir, ed (1957). "Oslobodilački rat naroda Jugoslavije 1941–1945" (in Serbian). Liberation War of the Peoples of Yugoslavia 1941–1945. Vojnoistorijski institut Jugoslovenske narodne armije. http://books.google.com/books?id=HF3jtgAACAAJ.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). "War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration". Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=fqUSGevFe5MC.

- Trikić, Savo; Rapajić, Dušan (1982). "Proleterski bataljon Bosanske Krajine" (in Serbian). Proletarian Battalion of Bosanska Krajina. Vojnoizdavački zavod. http://books.google.com/books?id=I8GSNAAACAAJ.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1949). "Yugoslavia". In Robert Joseph Kerner. University of California Press – via Questia (subscription required). http://www.questia.com/read/95013772/yugoslavia.

- Vukmanović, Svetozar (1982). "Revolucija koja teče: Memoari" (in Serbian). The Unfolding Revolution: Memoirs. Globus.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mladen Stojanović. |

- Gallery of photographs of Mladen Stojanović

- Ide Mladen vodi partizane. Song about Mladen Stojanović composed in Kozara in World War II

| |||||

The original article can be found at Mladen Stojanović and the edit history here.