| Internal Conflict in Peru | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

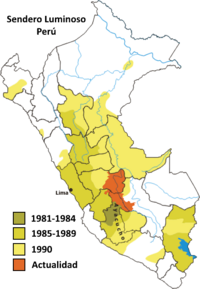

Areas where Shining Path was active in Peru. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000 (peak) >500 (2012)[2] | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 70,000 | |||||||

It has been estimated that nearly 70,000 people have died in the internal conflict in Peru that started in 1980, an ongoing conflict that is thought to have wound down by 2000. The principal actors in the war were the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) and the government of Peru.

A great many of the victims of the conflict were ordinary civilians. All of the armed actors in the war deliberately targeted and killed civilians, making the conflict more bloody than any other war in Peruvian history since the European colonization of the country. It is the third longest internal conflict in Latin America with the Colombian armed conflict being the first and the Guatemalan Civil War being the second.

National situation before the war[]

Notwithstanding its long historical stability, Peru has had a succession of authoritarian and democratic governments. General Juan Velasco Alvarado staged a military coup in 1968 and led a left-leaning government until 1975. Francisco Morales Bermúdez was installed as the new President of Peru in 1975, and allowed elections to be held in 1980.

Rise of Shining Path[]

During the governments of Velasco and Morales, Shining Path had organized as a Maoist political group based at the San Cristóbal of Huamanga University in the Ayacucho Region. The group was led by Abimael Guzmán, a communist professor of philosophy at the San Cristóbal of Huamanga University. Guzmán had been inspired by the Cultural Revolution, which he had witnessed firsthand during a trip to China. Shining Path members engaged in street fights with members of other political groups and painted graffiti exhorting "armed struggle" against the Peruvian state.

Outbreak of hostilities[]

When Peru's military government allowed elections for the first time in a dozen years in 1980, Shining Path was one of the few leftist political groups that declined to take part, instead opting to launch a guerrilla war against the state in the highlands of the province of Ayacucho. On May 17, 1980, the eve of the presidential elections, it burned ballot boxes in the town of Chuschi, Ayacucho. It was the first "act of terrorism" by Shining Path. Nonetheless, the perpetrators were quickly caught, additional ballots were brought in to replace the burned ballots, the elections proceeded without further incident, and the act received very little attention in the Peruvian press.[3]

Shining Path opted to fight their war in the style taught by Mao Zedong. They would open up "guerrilla zones" in which their guerrillas could operate, drive government forces out of these zones to create "liberated zones", then use these zones to support new guerrilla zones until the entire country was essentially one big "liberated zone." Shining Path also adhered to Mao's teaching that guerrilla war should be fought primarily in the countryside and gradually choke off the cities.

On December 3, 1982, the Shining Path officially formed the "People's Guerrilla Army", its armed wing.

Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement[]

The flag of the MRTA

In 1982, the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) launched its own guerrilla war against the Peruvian state. The group had been formed by remnants of the Movement of the Revolutionary Left in Peru and identified with Castroite guerrilla movements in other parts of Latin America. The MRTA used techniques that were more traditional to Latin American leftist organizations than those used by Shining Path. For example, the MRTA wore uniforms, claimed to be fighting for true democracy, and complained of human rights abuses by the state, while Shining Path did not wear uniforms, and had little regard for the democratic process and human rights.[4]

During the internal conflict, the MRTA and Shining Path engaged in combat with each other. The MRTA played a small part in the overall internal conflict, being declared by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to have been responsible for 1.5% of deaths accumulated throughout the war. At its height the MRTA was believed to consist of only a few hundred members.[4]

Government response[]

Gradually the Shining Path committed more and more violent attacks on the National Police of Peru, and the Lima-based government could no longer ignore the growing crisis in the Andes.[citation needed] In 1981, Fernando Belaúnde Terry declared a State of Emergency and ordered that the Peruvian Armed Forces fight the Shining Path.[citation needed] Constitutional rights were suspended for 60 days in Huamanga Province, Huanta Province, Cangallo Province, La Mar Province and Víctor Fajardo Province.[citation needed] Later, the Armed Forces created the Ayacucho Emergency Zone, in which military power was superior to civilian power, and many constitutional rights were suspended.[citation needed] The military committed many human rights violations in the area where it had political control, including the infamous Accomarca massacre. Scores of peasants were massacred by the armed forces.[5] A special US-trained "counterterrorist" police battalion known as the "Sinchis" were particularly notorious in the '80s for their human rights violations.[6]

Escalation of the war[]

The reaction of the Shining Path to the Peruvian government's use of the military in the war was not to back down, but instead to ramp up the level of violence in the countryside. Shining Path attacked police, military, and civilians that it considered to be "class enemies", often using particularly gruesome methods of killing their victims. These killings, along with Shining Path's disrespect for the culture of indigenous peasants it claimed to represent, turned many people in the sierra away from the Shining Path.

Faced with a hostile population, the Shining Path's guerrilla war began to falter. In some areas, peasants formed anti-Shining Path patrols, called rondas. They were generally poorly equipped despite donations of guns from the armed forces. Nevertheless, Shining Path guerrillas were militarily attacked by the rondas. The first such reported attack was in January 1983 near Huata, when some rondas killed 13 senderistas; in February in Sacsamarca, rondas stabbed and killed the Shining Path commanders of that area. In March 1983, rondas brutally killed Olegario Curitomay, one of the commanders of the town of Lucanamarca. They took him to the town square, stoned him, stabbed him, set him on fire, and finally shot him.[7] As a response, in April, Shining Path entered the province of Huancasancos and the towns of Yanaccollpa, Ataccara, Llacchua, Muylacruz and Lucanamarca, and killed 69 people, many of whom were children, including one who was only six months old.[7] Also killed were several women, some of them pregnant.[7] Most of them died by machete hacks, and some were shot at close range in the head.[7] This was the first massacre by Shining Path of the peasant community. Other incidents followed, such as the one in Hauyllo, Tambo District, La Mar Province, Ayacucho Department. In that community, Shining Path killed 47 peasants, including 14 children aged four to fifteen.[8]

Additional massacres by Shining Path occurred, such as one in Marcas on August 29, 1985.[9][10]

The Shining Path, like the government, filled its ranks by conscription. The Shining Path also kidnapped children and forced them to fight as child soldiers in their war.

The administration of Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000) and decline[]

Under the administration of Alberto Fujimori the state began the widespread use of intelligence agencies in its fight against Shining Path. Some atrocities were allegedly committed by the National Intelligence Service, notably the La Cantuta massacre, the Barrios Altos massacre, and the Santa massacre.

On April 5, 1992, Alberto Fujimori dissolved the Congress of Peru and abolished the Constitution, initiating the Peruvian Constitutional Crisis of 1992. The pretext for these actions was that the Congress was slow to pass anti-terrorism legislation. Fujimori set up military courts to try suspected members of the Shining Path and MRTA, and ordered that an "iron fist" approach be used. Fujimori also announced that Peru would no longer accept the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

As Shining Path began to lose ground in the Andes to the Peruvian state and the rondas, it decided to speed up its overall strategic plan. Shining Path declared that, in Maoist terminology, it had reached "strategic equilibrium" and was ready to begin its final assault on the cities of Peru. In 1992, Shining Path set off a powerful bomb in the Miraflores District of Lima in what became known as the Tarata bombing. This was part of a larger bombing campaign in Lima.

On September 12, 1992, Peruvian police captured Guzmán and several Shining Path leaders in an apartment above a dance studio in the Surquillo district of Lima. The police had been monitoring the apartment, as a number of suspected Shining Path militants had visited it. An inspection of the garbage of the apartment produced empty tubes of a skin cream used to treat psoriasis, a condition that Guzmán was known to have. Shortly after the raid that captured Guzmán, most of the remaining Shining Path leadership fell as well.[11] At the same time, Shining Path suffered embarrassing military defeats to campesino self-defense organizations – supposedly its social base – and the organization fractured into splinter groups.[citation needed] Guzmán's role as the leader of Shining Path was taken over by Óscar Ramírez, who himself was captured by Peruvian authorities in 1999. After Ramírez's capture, the group splintered, guerrilla activity diminished sharply, and previous conditions returned to the areas where the Shining Path had been active.[12]

Shining Path confined to their former headquarters in the Peruvian jungle and continued smaller attacks against the state, like the one occurred on October 2, 1999 when a Peruvian Army helicopter was shot down by SP guerrillas near Satipo (killing 5) and stealing a PKM machine gun which was reportedly used in another attack against an Mi-17 in July 2003.[13]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission[]

Alberto Fujimori resigned the Presidency in 2000, but Congress declared him "morally unfit", installing to oppositor congressmember Valentín Paniagua into office. He rescinded Fujimori's announcement that Peru would leave the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate the war. The Commission found in its 2003 Final Report that 69,280 people died or disappeared between 1980 and 2000 as a result of the armed conflict.[14] A statistical analysis of the available data led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to estimate that the Shining Path was responsible for the death or disappearance of 31,331 people, 46% of the total deaths and disappearances.[14] According to a summary of the report by Human Rights Watch, "Shining Path... killed about half the victims, and roughly one-third died at the hands of government security forces... The commission attributed some of the other slayings to a smaller guerrilla group and local militias. The rest remain unattributed."[15] According to its final report, 75% of the people who were either killed or disappeared spoke Quechua as their native language, despite the fact that the 1993 census found that only 20% of Peruvians speak Quechua or another indigenous language as their native language.[16]

Nevertheless, the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was surrounded by controversy. It was criticized by almost all political parties[17][18] (including former Presidents Fujimori,[19] García[20] and Paniagua[21]), the military and the Catholic Church,[22] which claimed that many of the Commission members were former members of extreme leftists movements and that the final report wrongfully portrayed Shining Path and the MRTA as "political parties" rather than as terrorist organizations,[23] even though, for example, Shining Path has been clearly designated as a terrorist organization by the United States, the European Union, and Canada.[24]

21st century reemergence (2002–present)[]

Comrade Artemio makes demands of the Peruvian government

On March 20, 2002, a car bomb exploded at "El Polo", a mall on an upper scale district of Lima near the US embassy.[25]

On June 9, 2003 a Shining Path group attacked a camp in Ayacucho, and took 68 employees of the Argentine company Techint and three police guards as hostages. They had been working in the Camisea gas pipeline project that would take natural gas from Cuzco to Lima.[26] According to sources from Peru's Interior Ministry, the hostage-takers asked for a sizable ransom to free the hostages. Two days later, after a rapid military response, the hostage-takers abandoned the hostages. According to rumor, the company paid the ransom.[27]

On October 13, 2006, Guzmán was sentenced to life in prison for terrorism.[28]

On May 27, 2007, the 27th anniversary of the Shining Path's first attack against the Peruvian state, a homemade bomb in a backpack was set off in a market in the southern Peruvian city of Juliaca, killing six and wounding 48. Because of the timing of the attack the Shining Path is suspected by the Peruvian authorities of holding responsibility.[29]

In October 2008, in Huancavelica province, the senderistas engaged a military and civil convoy with explosives and firearms, demonstrating their continued ability to strike and inflict casualties on easy targets. The clash resulted in the death of 12 soldiers and two to seven civilians.[30][31]

On April 9, 2009, Shining Path ambushed and killed 13 Peruvian soldiers in the Apurímac and Ene river valleys in Ayacucho, said Peruvian minister of Defense, Antero Flores-Aráoz.[32]

The group was, until recently, led by a man known as Comrade Artemio. Rather than attempt to destroy the Peruvian state and replace it with a communist state, Artemio pledged to carry out attacks until the Peruvian government releases Shining Path 'prisoners' and negotiates an end to the 'war'. These demands were made in various video statements made by Artemio. The vast majority of Peruvians continue to hold the Shining Path in low regard.[citation needed]

On February 12, 2012, Artemio was captured by a combined force of the Peruvian Army and the Police. President Ollanta Humala said that he would now step up the fight against the other remaining band of Shining Path rebels in the Ene-Apurimac valley.[33]

In May 2012 it was reported that, since 2008, 71 security forces personnel had been killed and 59 wounded by Shining Path ambushes in the VRAE region.[34]

See also[]

- 2009 Peruvian political crisis

- Shining Path

- Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement

- List of designated terrorist organizations

References[]

- ↑ "Americas | Profile: Peru's Shining Path". BBC News. 2004-11-05. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/3985659.stm. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=39249

- ↑ The Shining Path: A History of the Millenarian War in Peru. p. 17. Gorriti, Gustavo trans. Robin Kirk, The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill and London, 1999 (ISBN 0-8078-4676-7).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Final Report. "General Conclusions." Available online. Accessed February 3, 2007.

- ↑ BBC News. "Peruvians seek relatives in mass grave." June 12, 2008. Available online. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Palmer, David Scott (2007). The revolutionary terrorism of Peru's Shining Path. In Martha Crenshaw, Ed. Terrorism in Context. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. "La Masacre de Lucanamarca (1983)." August 28, 2003. Available online in Spanish Accessed February 1, 2006.

- ↑ Amnesty International. "Peru: Human rights in a time of impunity." February 2006. Available online. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ↑ La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. "Ataque del PCP-SL a la Localidad de Marcas (1985)." Available online in Spanish Accessed February 1, 2006.

- ↑ La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. "Press Release 170." Available online Accessed February 1, 2006.

- ↑ Rochlin, James F. Vanguard Revolutionaries in Latin America: Peru, Colombia, Mexico. p. 71. Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder and London, 2003. (ISBN 1-58826-106-9).

- ↑ Rochlin, James F. Vanguard Revolutionaries in Latin America: Peru, Colombia, Mexico. pp. 71–72. Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder and London, 2003. (ISBN 1-58826-106-9).

- ↑ "INVESTIGACIÓN | Sendero atacó helicóptero en el que viajaba general EP". agenciaperu.com. http://agenciaperu.com/investigacion/2003/jul/helicoptero.htm. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Annex 2 Page 17. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch. August 28, 2003. "Peru – Prosecutions Should Follow Truth Commission Report". Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- ↑ CVR. Tomo VIII. Chapter 2. "El impacto diferenciado de la violencia" "2.1 VIOLENCIA Y DESIGUALDAD RACIAL Y ÉTNICA" pp. 131–132 [1]

- ↑ Agencia Perú – Reactions to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- ↑ Frecuencia Latina – Xavier Barrón

- ↑ BBC Mundo – Fujimori: "Sería ingenuo participar en este circo que la Comisión de la Verdad está montando"

- ↑ Agencia Perú – Alan García: "Cifras obedecen a un juego de probabilidades"

- ↑ Agencia Perú – Former President Valentín Paniagua: Shining Path and Political Parties are not the same

- ↑ Agencia Perú – Cipriani: "No acepto informe de la CVR por no ser la verdad"

- ↑ Agencia Perú – Macher: Shining Path is a political party

- ↑ List of designated terrorist organizations

- ↑ http://www.lacuarta.cl/diario/2002/03/21/21.10.4a.VUE.LIMA.html

- ↑ The New York Times. "Pipeline Workers Kidnapped." June 10, 2003. nytimes.com. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ↑ Americas.org "Gas Workers Kidnapped, Freed." americas.org.

- ↑ Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. October 13, 2006. Shining Path militant leaders given life sentences in Peru. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Blast kills six in southern Peru" May 20, 2007 BBC

- ↑ BBC Peru rebels launch deadly ambush. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ↑ Associated Press Peru says 14 killed in Shining Path attack. Retrieved October 10, 2008.[dead link]

- ↑ BBC Rebels kill 13 soldiers in Peru. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- ↑ "BBC News – Peru Shining Path leader Comrade Artemio captured". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-02-13. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-17005739. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ http://www.rpp.com.pe/2012-05-12-sendero-mato-a-71-militares-y-policias-en-el-vrae-desde-2008-informan-noticia_481181.html

External links[]

The original article can be found at Internal conflict in Peru and the edit history here.