The Hungarian invasions of Europe took place in the 9th and 10th centuries, at a time when three groups were attacking Europe: the Vikings, the Muslims and the Hungarians.[1][2] In the short run, the Hungarians wreaked havoc on land and people; in the long run, they were absorbed into the European population and became constituents of European civilization.[1]

History[]

Before the conquest of Hungary (9th century)[]

The Hungarians at Kiev (Pál Vágó, 1896-99)

The first supposed reference to the Hungarians in war is in the 9th century: in 811, the Hungarians (Magyars) were in alliance with Krum of Bulgaria against Emperor Nikephoros I possibly at Battle of Pliska in the Haemus Mountains (Balkan Mountains).[3] Georgius Monachus' work mentions that around 837 the Bulgarian Empire sought an alliance with the Hungarians.[3][4] Constantine Porphyrogenitus wrote in his work On Administering the Empire that the Khagan and the Bek of the Khazars asked the Emperor Teophilos to have the fortress of Sarkel built for them.[4] This record is thought to refer to the Hungarians on the basis that the new fortress must have become necessary because of the appearance of a new enemy of the Khazars, and no other people could have been the Khazars’ enemy at that time.[4] In the 10th century, Ahmad ibn Rustah wrote that "earlier, the Khazars entrenched themselves against the attacks of the Magyars and other peoples".[4]

In 860–861, Hungarian soldiers attacked Saint Cyril's convoy but the meeting is said to have ended peacefully.[3] Saint Cyril was traveling to the Khagan at (or near) Chersonesos Taurica, which had been captured by the Khazars. Muslim geographers recorded that the Magyars regularly attacked the neighboring East Slavic tribes, and took captives to sell to the Byzantine Empire at Kerch.[5][6] There is some information about Hungarian raids into the eastern Carolingian Empire in 862.[7]

In 881, the Hungarians and the Kabars invaded East Francia and fought two battles, the first (Ungari) at Wenia (probably Vienna)[7] and the second (Cowari) at Culmite (possibly Kulmberg or Kollmitz in Austria).[8] In 892, according to the Annales Fuldenses, King Arnulf of East Francia invaded Great Moravia and the Magyars joined his troops.[4][7] After 893, Magyar troops were conveyed across the Danube by the Byzantine fleet and defeated the Bulgarians in three battles (at the Danube, Silistra and Preslav).[6] In 894, the Magyars invaded Pannonia in alliance with King Svatopluk I of Moravia.[4][7]

After the conquest of Hungary (10th century)[]

Fresco about a Hungarian warrior (Italy)

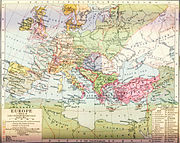

Europe around 900

Grand Prince Árpád's sculpture in Budapest

Around 896,[9] probably under the leadership of Árpád, the Hungarians (Magyars) crossed the Carpathians and entered the Carpathian Basin (the plains of Hungary, approximately). In 899, these Magyars invaded the northern regions of Italy and pillaged the countryside around Treviso, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, Bergamo and Milan.[6] They also defeated Knez (Prince) Braslav of Pannonian Croatia. In 901, they attacked Italy again.[10] In 902, they led a campaign against northern Moravia and defeated the Moravians whose country was annihilated.[6] Almost every year after 900 they conducted raids against the Catholic west and Byzantine east. In 905, the Magyars and King Berengar formed an amicitia, and fifteen years passed without Hungarian troops entering Italy.[11]

The Magyars defeated no fewer than three major East Frankish armies between 907 and 910 in fast and devastating raids, as follows.[12] In 907 they defeated the invading Bavarians near Brezalauspurc, destroying their army, successfully defending Hungary and laying Great Moravia, Germany, France and Italy open to Magyar raids. On 3 August 908 the Hungarians won the battle of Eisenach, Thuringia.[8] Egino, Duke of Thuringia was killed, along with Burchard, Duke of Thuringia and Rudolf I, Bishop of Würzburg.[13] The Magyars defeated Louis the Child's united Frankish Imperial Army near Augsburg in 910.

Smaller units penetrated as far as Bremen in 915.[14] In 919, after the death of Conrad I of Germany, the Magyars raided Saxony, Lotharingia and West Francia. In 921, they defeated King Berengar's enemies at Verona and reached Apulia in 922.[11] Between 917 and 925, the Magyars raided through Basle, Alsace, Burgundy, Provence and the Pyrenees.[14] Around 925, according to the Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea from the late 12th century, Tomislav of Croatia defeated the Magyars in battle,[15] however others question the reliability of this account, because there is no proof for this interpretation in other records.[15]

In 926, they ravaged Swabia and Alsace, campaigned through present-day Luxembourg and reached as far as the Atlantic Ocean.[11] In 927, Peter, brother of Pope John X, called on the Magyars to rule Italy.[11] They marched into Rome and imposed large tribute payments on Tuscany and Tarento.[11][14] In 933, a substantial Magyar army appeared in Saxony (the pact with the Saxons having expired) but was defeated by Henry I at Merseburg.[11] Magyar attacks continued against Upper Burgundy (in 935) and against Saxony (in 936).[11] In 937, they raided France as far west as Reims, Lotharingia, Swabia, Franconia, the Duchy of Burgundy[16] and Italy as far as Otranto in the south.[11] They attacked Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire, reaching the walls of Constantinople. The Byzantines paid them a “tax” for 15 years.[17] In 938, the Magyars repeatedly attacked Saxony.[11] In 940, they ravaged the region of Rome.[11] In 942, Hungarian raids on Spain, particularly in Catalonia,[18] took place, according to Ibn Hayyan's work.[19] In 947, Taksony led a raid into Italy as far as Apulia, and King Berengar II of Italy had to buy peace by paying a large amount of money to him and his followers. Magyar expansion was finally checked at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, although raids on the Byzantine Empire continued until 970.

Tactics[]

Hungarian warriors (oil on canvas)

Their army had mostly light cavalry and were highly mobile.[20] Attacking without warning, they quickly plundered the countryside and departed before any defensive force could be organized.[20] If forced to fight, they would harass their enemies with arrows then sudden retreat, tempting their opponents to break ranks and pursue, after which the Hungarians would turn to fight them singly.[20]

Aftermath[]

The Hungarians were the last invading people to establish a permanent presence in Central Europe.[20] In the following centuries, the Hungarians settled down in Hungary and adopted western European forms of feudal military organization, including the predominant use of heavily armored cavalry.[20]

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Barbara H. Rosenwein, A short history of the Middle Ages, University of Toronto Press, 2009, p. 152 [1]

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Duroselle, Europe: a history of its peoples, Viking, 1990, p. 124 [2]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Király, Péter. Gondolatok a kalandozásokról M. G. Kellner "Ungarneinfälle..." könyve kapcsán . http://www.c3.hu/~magyarnyelv/00-1/kiraly.htm.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levediától a Kárpát-medencéig (From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 963-482-175-8.

- ↑ Kevin Alan Brook, The Jews of Khazaria, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, p. 142.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kristó, Gyula (1993). A Kárpát-medence és a magyarság régmultja (1301-ig) (The ancient history of the Carpathian Basin and the Hungarians - till 1301). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 299. ISBN 963-04-2914-4. http://www.antikvarium.hu/ant/book.php?ID=39250.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Victor Spinei, Text to be displayedThe Romanians and the Turkic nomads north of the Danube Delta from the tenth to the mid-thirteenth century, BRILL, 2009, p. 69

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Csorba, Csaba (1997). Árpád népe (Árpád’s people). Budapest: Kulturtrade. p. 193. ISBN 963-9069-20-5. http://openlibrary.org/works/OL982521W/Árpád_népe.

- ↑ Gyula Kristó, Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History - 9-14th centuries[3]

- ↑ Lajos Gubcsi, Hungary in the Carpathian Basin, MoD Zrínyi Media Ltd, 2011

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Timothy Reuter, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900-c. 1024, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 543, ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8

- ↑ Peter Heather, Empires and Barbarians, Pan Macmillan, 2011

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991., p. 129

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 13

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Florin Curta, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 193, ISBN 978-0521815390

- ↑ Karl Leyser, Medieval Germany and its neighbours, 900-1250, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1982, p. 50 [4]

- ↑ The Magyars of Hungary

- ↑ Various authors, Santa Coloma de Farners a l'alta edat mitjana: La vila, l'ermita, el castell in Catalan

- ↑ Elter, I. (1981) Remarks on Ibn Hayyan's report on the Magyar raids on Spain, Magyar Nyelv 77, p. 413-419

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Stanley Sandler, Ground warfare: an international encyclopedia, Volume 1, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 527

External links[]

The original article can be found at Hungarian invasions of Europe and the edit history here.