| George Maxwell Robeson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 26th United States Secretary of the Navy | |

In office June 25, 1869 – March 12, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | Adolph E. Borie |

| Succeeded by | Richard W. Thompson |

| New Jersey Attorney General | |

In office 1867–1869 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick T. Frelinghuysen |

| New Jersey's 1st congressional district | |

In office March 4, 1879 – March 3, 1883 | |

| Preceded by | Clement Hall Sinnickson |

| Succeeded by | Thomas M. Ferrell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16, 1829 Oxford Furnace, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | September 27, 1897 (aged 68) Trenton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | New Jersey Militia |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

George Maxwell Robeson (March 16, 1829 – September 27, 1897) was an American Republican Party politician and lawyer from New Jersey who served as a Union army general during the American Civil War, and then as Secretary of the Navy during the Grant Administration. During the 19th Century, Sec. Robeson's seven years in office as Secretary of Navy was second in time length only to Sec. Gideon Welles's tenure. Robeson, as Secretary of Navy, was an industrious administrator and through his strong departmental leadership was able to contain the established Naval officer hierarchy. Sec. Robeson supported and developed the early stages of submarine and torpedo technology in keeping U.S. harbors safe from foreign attack. Sec. Robeson secured $50,000 in Congressional funding for the 1871 Polaris expedition led by Capt. C. F. Hall. Secretary Robeson investigated the death of Capt. Hall after the return of the Polaris crew in 1873. During Reconstruction, Sec. Robeson was a scholarly and forceful advocate of President Grant and the Radical Republican agenda to end the Southern vestiges of slavery having supported the citizenship and voting rights for the African American freedmen. In 1874, Sec. Robeson responded to the naval threat imposed by Spain during the Virginius Affair; having implemented U.S. Naval resurgence; however Congress refused to pay for the completion of the five new ships. Robeson was the subject of two Congressional investigations in 1876 and 1878 concerning profiting and bribery charges from ship building contracts. No paper trail could be adequately established and Robeson was exhonerated. Robeson served briefly as both Secretary of Navy and as ad interim Secretary of War after Secretary of War William W. Belknap abruptly resigned in 1876.

Robeson, a native of New Jersey, graduated from Princeton University at the young age of 18. Robeson studied law and passed the bar in 1850. Practicing law, Robeson diligently worked his way through the legal profession and in 1858 he was appointed public prosecutor for Camden County. During the American Civil War Robeson associated with the Republican Party and was a member of the New Jersey Sanitary Commission . Appointed Brigadier General by Governor Charles S. Olden, Robeson worked to recruit enlistments to fight for the Union. After the war in 1867, Robeson was appointed New Jersey Attorney General by Gov. Marcus L. Ward. Robeson, as Attorney General, gained national attention after successfully prosecuting Bridget Durgan for the brutal murder of Mrs. Coriell. Supported by New Jersey Senator A.G. Cattell, Robeson was appointed Secretary of Navy by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869 after Sec. Adolph E. Borie had resigned office.

After Robeson resigned as Secretary of the Navy in 1877, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in both 1878 and 1880. Robeson's grandfather was George C. Maxwell and he was nephew of John Patterson Bryan Maxwell, both of whom also represented New Jersey in the House of Representatives. As U.S. Representative for New Jersey, Congressman Robeson served as minority leader of the Republican Party. Robeson was defeated from office by Thomas M. Ferrell in a bitter election campaign held in 1882. The highly contested election loss left the embittered Robeson $60,000 in debt and he was forced to sell his Washington property. As a result of Robeson's financial trouble, his wife and family left him and traveled abroad. Robeson moved to Trenton and resumed his law practice until his death in 1897. Due to his strikingly distinguished personal traits and size, Robeson was one of the most caricatured individuals during the 19th Century by cartoonists.[1]

Early life[]

George M. Robeson was born on March 16, 1829 in Oxford Furnace, New Jersey, near Belvidere in Warren County.[2][3] His father was Philadelphia Judge William P. Robeson and his mother was the daughter of U.S. Congressman George C. Maxwell, who served in the 12th U.S. Congress from 1811 to 1813 representing Hunterdon, New Jersey.[2] Robeson's family was of Scotch origin and he was a descendant of Andrew Robeson, the surveyor-general of New Jersey in 1668.[4] Robeson was the nephew of U.S. Congressman John Patterson Bryan Maxwell.[5] Robeson gained a scholarly reputation by having graduated from Princeton University at the early age of 18 in 1847.[2] Upon graduation, Robeson studied law in Newark in Chief Justice Hornblower's law office.[2][6] Robeson graduated and was admitted to the bar in 1850.[2] Robeson was admitted as a legal counselor in 1854.[2] Robeson initially set up his law practice in Newark, but then moved his practice to Jersey City.[2] In 1858, Robeson was appointed public prosecutor for Camden County.[3]

Civil War[]

During the Civil War, he was appointed a brigadier general in the New Jersey Militia by the Governor of New Jersey.[3]

Attorney General New Jersey[]

Robeson served as the Attorney General of New Jersey from 1867 to 1869.[3] Robeson resigned as Attorney General on June 22, 1869 to become United States Secretary of the Navy.[6]

Coriell murder trial[]

In May, 1867 Robeson gained national attention after successfully prosecuting Bridget Durgan of brutally murdering Mrs. Mary Ellen Coriell, Dr. Coriell's wife.[7] Robeson was able to gain a conviction of Durgan on circumstantial evidence. Durgan, having a previous criminal record, had murdered Mrs. Coriell by stabbing her several times with a kitchen knife, believing that she would take over as wife of Dr. Coriell and would raise Mrs. Coriell's child.[7] Robeson had stated that blood on Durgan's dress was the blood of Mrs. Coriell after a violent struggle to save her life had taken place. Robeson told the jury not to take into consideration the sex of Durgan when making a verdict. Throughout Robeson's closing arguments, Durgan held her head low and constantly had a handkerchief to her eyes. Robeson was applauded by the courtroom audience after he finished giving his closing arguments. The jury only took one hour to deliberate before reaching a verdict. Durgan was convicted by the jury of murder, sentenced to death, and hanged on August 30, 1867.[7]

[]

President Ulysses S. Grant appointed George M. Robeson Secretary of Navy on June 25, 1869, having replaced Sec. Adolph E. Borie, who resigned on same day[8] Robeson would become one of the longest held cabinet Naval secretary positions, with the exception of Sec. Gideon Welles, and would serve until March 12, 1877 at the end of President Grant's second term in office and at the beginning of President Hayes's Administration.[8] This was Robeson's first position on being given national federal authority and he had no previous affiliation with Naval ships.[8] Robeson, however, was familiar with ocean lifestyle having grown up in New Jersey.[8] Robeson's appointment to the Secretary of Navy was influenced by Sen. A. G. Cattell of New Jersey.[8] Robeson, a young man around 40 upon assuming office, was considered an impatient administrator, high strung, and strong in physical prowess.[8]

Established department control (1869)[]

Robeson's predecessor Sec. Borie, Grant's first appointment, had let the Navy Department be run by Rear Admiral David D. Porter.[9] Borie, apparently did not have any interest in running the Navy Department, and let Porter have unprecedented authority.[9] All orders from the Naval Department had to go through Porter's office to be approved.[9] Porter ran the Naval Department autocratically making as many as 45 "arbitrary and extravagant" changes in the Naval Department in only two months.[9] Robeson, however, after his appointment in June 1869, assumed strong leadership of the Naval Department and Porter's dogmatic control immediately ended.[10] Sec. Robeson was not willing to be Porter's subordinate, as Borie had been.[10] Porter was virtually barred from the Navy Department Office building; only visiting 4 times during Robeson's tenure.[10] On November 16, 1870, Robeson wrote Porter a letter specifically stating Porter's limited authority and Porter was told to report regularly to Robeson's Naval Office in writing.[10]

Norfolk riot (1870)[]

During the Reconstruction Era, Secretary of the Navy Robeson arrived in Norfolk, Virginia on November 1, 1870 and he was saluted by naval warships in the harbor.[11] Robeson's purpose was to speak for and support Republican Rep. James H. Platt's reelection to the U.S. Congress.[11] During the stump speech ceremony in honor of Republican Congressman Platt, Robeson forcefully advocated Republican Radical Reconstruction.[11] Robeson in his scholarly manner on the steps of the Norfolk City Hall spoke on the Republican Party's achievements in successfully defeating the Southern Rebellion, ending the "barbarism of slavery", elevating millions of African American freedmen by giving them citizenship, full suffrage and education, having completed the Pacific Railroad, reducing taxes and paying off the Civil War debt.[11] Robeson, however, was abruptly interrupted by a Conservative who asked Robeson "If the Republicans have done so much for the slaves, what have they done for their masters?"[11] Robeson quickly replied that the Republican Party, after the War, had been very gracious to the South by limiting the punishment of hanging, "having destroyed the cause of the crime, to let the crime itself go unpunished".[11] Following Robeson, a riot broke out, eggs were thrown, and guns were fired. Several persons were wounded as the meeting broke up, however, Robeson was kept from harm.[11]

Polaris expedition (1871)[]

Harper's Weekly 1873

The Polaris expedition, commissioned by Secretary of Navy Robeson, was the United States first serious attempt at arctic exploration to be the first nation to reach the North Pole. On June 29, 1871, at 7 PM, the USS Polaris, sailed from the New York Naval Yard, under the authority of Captain Charles Francis Hall.[12] Sec. of Navy Robeson and Hall, who was on his third arctic expedition, had lobbied Congress successfully to fund the Polaris expedition. Robeson had written specific instructions on the objective of the mission and implemented a hierarchy of command in case Capt. Hall was injured or killed.[13] Robeson directed the course of the expedition, outfitted for two and one half years, giving extensive written instructions. According to Robeson, anything that was found on the expedition would be property of the U.S. Government. Robeson ordered that monuments would be erected on the journey, records and general conditions of the expedition be kept, and to establish food caches. The USS Polaris was supplied with every scientific instruments needed for such a dangerous and ambitious expedition.[14]

Polaris Expedition Route 1871-1873

While traveling west of Greenland under good weather, the Polaris broke a sailing record to the highest point northward at 82°29'N. In October 1871, the Polaris expedition established a winter camp on Thank God Bay in order to prepare reaching the North Pole by dog sled. On October 24, upon his return from an exploratory dog sled party, Captain Hall fell sick after drinking a cup of coffee. Historians now believe Hall was probably murdered by crewmember Dr. Emil Bessel, having been poisoned with arsenic.[15] Two weeks later, Captain Hall died, and Sidney O. Buddington was put in charge of the expedition, according to Robeson's instructions. Under Buddington's authority, discipline on the expedition declined as the crew was allowed to carry weapons and stay up all night. Buddington, himself, had raided the ships medical supply of alcohol and was known to have been drunk.[16] On June 2, 1872, after an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole, the Polaris expedition turned south to head back to the New York Navy Yard.[17] Having been caught in an ice pack, 19 crewmembers got separated from the ship on an ice flow and floated 1,800 miles before being rescued.[18] The remaining crew on board ship was forced to winter off Greenland in October 1872, with the USS Polaris being broken down into two ships. Setting out on the ocean, the remaining Polaris expedition crew was rescued by a whaling ship on June 3, 1873.

Upon the Polaris crews return, Robeson immediately opened a naval investigation on June 5, 1873 inquiring into Hall's death and Buddington's lack of leadership and crew discipline.[19] Captain Hall's journals and letters had been tampered with and destroyed that may have contained information that was detrimental to both Buddington and Dr. Bessel. The investigation under Robeson, however, did not charge Dr. Bessel with Hall's murder, although there was circumstantial evidence Dr. Bessel did murder Hall; however, the entire Polaris expedition crew was exonerated. In 1968, Captain Hall's body was exhumed and modern scientific testing revealed he had been poisoned by arsenic prior to his sudden sickness and death.[20] Dr. Bessel, who was in charge of Hall's medical care, is now believed to have most likely murdered Hall, since Dr. Bessel had patriotic ties with his mother country Germany rather than the U.S.[15][21] Robeson's final report stated Hall had died a "natural" death, however, certain information may have been suppressed to prevent scandal. Capt. Hall named Robeson Channel in honor of Sec. Robeson.

Submarine and torpedo testing (1872)[]

The Intelligent Whale currently on display at the Washington Navy Yard.

During Sec. Robeson's tenure, submarine and torpedo technology were tested by the U.S. Navy.[22] The Intelligent Whale, an experimental hand-cranked submarine, owned by Oliver Halstead, had been semi-officially successfully tested in 1866 by Thomas W. Sweeney, however, the U.S. Navy did nothing with the ship until October, 1869 when the ship was examined and recommended to Robeson by Cmdrs. C. Melancthon Smith, Augustus L. Case, and Edmund O. Matthews. Robeson appointed another committee to report on the boat's merit. After the second committee gave a favorable review, Robeson and Halstead signed a contract on October 29, 1869 to purchase the submarine for $50,000.Halstead, who contracted to test the submarine, was murdered and the testing of the Intelligent Whale was stalled for over a year. Because of lax security in 1872 a British officer Rear Adm. Edward Augustus Inglefield sneaked into the New York Navy Yard and inspected the secluded vessel mored on a wharf.[22] On September 18, 1872, the ship was officially tested by the U.S. Navy; it took on water due to a defective hatch seal. Although deemed a failure, the "Intelligent Whale" represented the U.S. Navy's interest and experimentation in "improving weapons systems" during the 1870s.[22] The first submarine to have been purchased and tested by the U.S. Navy was the Alligator in 1863 during the American Civil War.[23]

The testing of torpedoes proved to be more successful.[22] The Navy in 1869 established a torpedo station off of Newport, Rhode Island. The goal was to find inexpensive and effective underwater defense weapons. In the summer of 1872, inventor entrepreneur, John L. Lay's self-propelled remote control torpedo test proved a success for the Bureau of Ordnance. The torpedo testing during the 1870s was the foundation for modern American underwater warfare.[22] In 1873 and 1874 respectively the USS Alarm and the USS Intrepid were launched that deployed offensive projectile topedoes by steam. By 1875 all U.S. naval cruisers were outfitted with spar and towing torpedoes and naval officers were trained in their deployment.[24]

Virginius incident (1873)[]

The Spanish Butchery

Illustrations of U.S. naval response over the Virginius Incident.

Harper's Weekly 1873

On October 31, 1873 a Spanish warship, the Toronado, ran down and captured the Virginius, a U.S. merchant ship, that was smuggling in weapons and soldiers to aid Cuba's revolt from the mother country Spain.[25] The American public demanded war with Spain, as shocking news poured into the country that 53 British and American citizens who had joined up to aid the Cuban Insurrection were captured on the Virginius and shot to death by Spanish Naval authority. In addition to this incident, a state of the art Spanish warship was in port in New York Harbor, that excelled in lethal military technology compared to American warships. Robeson immediately responded by sending a flotilla of warships to Key West, Florida. However they were no match for any modern Spanish warships.[26] One U.S. officer had stated that two Spanish warships could have decimated the U.S. flotilla, the best ships the U.S. Navy could offer at the time.

During the Virginius crisis, Sec. Robeson decided that the primary goal for the Navy was a naval resurgence program to make monitor warships that could compete with foreign navies. Congress however refused to make new ships believing that the technology revolutionary ironclads made ten years ago somehow remained modern and were good enough for the U.S. Navy.[25] In a compromise, Robeson and Congress chose to "rebuild" five of the biggest U.S. warships including an unfinished USS Puritan and four USS Miantonomahs. The ships were contracted out, torn down and scrapped, to be "rebuilt" as new warships by various contractors approved by Sec. Robeson. Work began in 1874, however, Congress refused to give Robeson 2.3 million dollars to complete the ships. The almost complete USS Miantonomah, however, was launched on December 6, 1876. Robeson was criticized for scrapping other monitors to pay for the new monitors.[27] Secretary of State Hamilton Fish successfully and coolly arbitrated reparations with Spain over the Virginius Incident and war was prevented.[28] The Virginius Incident brought home the realities of having a weak navy and the need for naval resurgence.

Ordered warships (1874)[]

The USS Puritan, ordered in 1874 by Sec. Robeson, actively served during the Spanish American War bombarding Matanzas, Cuba on April 27, 1898.

In response to the Virginius Incident Sec. Robeson ordered five warships on June 23, 1874 to implement U.S. naval resurgence; all participated in the Spanish American War that started in 1898.[29] The "rebuilding" of the USS Puritan and four Miantonomohs were under the direction of Sec. Robeson where each ship was redesigned, scrapped, and rebuilt from almost all new iron works material.[30]

- USS Puritan (BM-1)

- USS Amphitrite (BM-2)

- USS Monadnock (BM-3)

- USS Terror (BM-4)

- USS Miantonomoh (BM-5)

House investigation (1876)[]

In his last year in office Robeson was investigated by Congress; while no charges were made at the time, the House report was negative[31] and historians argue that he was exceedingly careless and partisan in his role as Secretary.[32]

In July 1876, the House Committee on Naval Affairs, controlled by Democrats, launched an investigation.;[33] it found the Robeson had made deposits totaling $320,000 to his bank account between 1872 and 1876. Robeson, while Secretary of Navy, allegedly took $320,000 in bribes from a grain company to pay for a new vacation home.[34] Robeson was also suspected by a House committee to have squandered $15,000,000 of missing Naval construction funds to purchase real estate in Washington. Robeson was so adept at hiding his financial tracks that he was known as "the cuttle fish" of the Navy.[35] The Naval Committee's, all Democratic majority report stated Sec. Robeson had run a "system of corruption" and recommended that he either be impeached to the House Judiciary Committee or that reform laws be made by Congress. No articles of impeachment were drawn up for Robeson, apparently due to Grant's second term was ending. Grant did not ask Robeson to resign and the Naval Committees minority Republican report exonerated Robeson.[33]

Legal and Congressional career[]

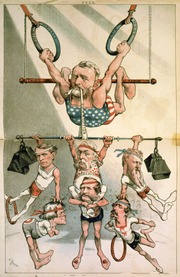

Robeson was lampooned by Democratic magazine Puck, due to his distinguished facial features.

Keppler 1880

After leaving the Navy Department in 1877 Robeson returned to his law practice in Camden County.[36] In 1878, Robeson ran for and was elected to the U.S. Congress and served as U.S. Congressman representing New Jersey's 1st congressional district starting on March 4, 1879 until March 4, 1881.[36] Robeson was elected a second term in 1880 serving from March 4, 1881 to March 3, 1883.[36] During the 1882 election Robeson was defeated by Democrat Thomas M. Ferrell in a bitter campaign that left Robeson financially in debt $60,000 and he was forced to sell his Washington D.C. property.[37] Robeson's political enemy, New Jersey U.S. Senator William J. Sewell, a Republican, was behind Democratic Party Ferrel's successful campaign; as a result of the election loss Robeson moved from Camden to Trenton and established a law practice having been induced to represent the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[37] The election loss caused contention between his wife and family and everyone in New Jersey who knew the intellectual Robeson, called him "Poor Roby". His family having left him, a friend, James L. Hayes, selected a small house near the State House in Trenton where Robeson lived and practiced law. Robeson lived a modest bachelor lifestyle in stark contrast to his luxurious home while he was Secretary of the Navy in the Grant Administration. In 1891, Robeson became interested in running for U.S. Congressman for a fourth time, however, the Trenton district was content with the Democratic ticket, and nothing became of Robeson's inquiry into public office.[37]

In 1885, Robeson was sued for $297 by John Cambell, a livery man, who had aided Robeson during his 1882 First Congressional District election campaign.[38] Cambell had organized horses, the Sixth Regiment Band, and security for Robeson in support of the Republican ticket. Robeson at the time was Treasurer of the Camden County Republican Executive Committee, and Cambell claimed that Robeson did not pay him for his services.[38] Robeson stated that he had paid $75 to the leader of the band and that he paid $258 to 11 constables who were hired for security. Robeson stated he did not believe that the hire of security and the band was necessary. Robeson also stated he had paid Cambell a check for $500 in addition to $300 for "political purposes". Robeson admitted he owed Cambell $42 for the hire of carriages. The jury returned a verdict that agreed with Robeson and Cambell was awarded $42 plus three years interest. Justice Park on the Camden County Circuit Court presided over Robeson's lawsuit trial.[38]

Death[]

Robeson continued practicing law until his death at the age of 68 on November 27, 1897. Robeson is buried at Belvidere Cemetery in Belvidere, New Jersey.

Marriage and family[]

On January 23, 1872 Robeson married Mary Isabella (Ogston) Aulick, a widow with a son, Richmond Aulick.[39] Robeson and Mary had a daughter named Ethel Maxwell, who married William Sterling, the son of British Maj. John Barton Sterling, on November 22, 1910 in Christ Church, Mayfair, England.[39][40] Mary's son, Richmond, graduated from Princeton University in 1889.[39] After Robeson lost an embittered 1882 Congressional election, his wife and family left him and the United States having went abroad, since Robeson had become financially in debt due to the hard fought unsuccessful campaign.[37]

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, p. 31

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Chicago Daily Tribune (Sep 28, 1897), George M. Robeson Dies

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Robeson, George Maxwell (1829–1897)

- ↑ The Biographical Dictionary of American Biography (1906), p. 38

- ↑ The Political Graveyard, Robeson, George Maxwell (1829–1897)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Biographical Dictionary of America, 138

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 New York Times (June 1, 1867), The Coriell Murder, Accessed on 02-22-2013

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Paullin (1913), Naval Institute proceedings, Volume 39, p. 751

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Paullin (1913), Naval Institute proceedings, Volume 39, pp. 748-749

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Paullin (1913), Naval Institute proceedings, Volume 39, p. 750

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 New York Times (November 7, 1870), The Riot at Norfolk, Va.; Washington Chronicle (November 2, 1870)

- ↑ Tyson (1874), pp. 107, 108

- ↑ Tyson (1874), p. 108

- ↑ Tyson (1874), pp. 108-109

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Parry (2001), p. 415

- ↑ Parry (2001), pp. 269, 285

- ↑ Parry (2001), p. 155

- ↑ Mowat (1967), p. 162

- ↑ Parry (2001), p. 265

- ↑ Berton (1988), p. 390

- ↑ Berton (1988), p. 392

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Undersea Warfare (Summer 2008), Issue 38

- ↑ The Navy and Marine Living History Association, The story of the Alligator

- ↑ Robeson (1875), Report of the Secretary of Navy

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Friedman (1985), p. 406

- ↑ O'Toole (1984), p. 44

- ↑ Friedman (1985), p. 405

- ↑ Schwartz (October 1998), 1873 One Hundred And Twenty-five Years Ago

- ↑ Friedman (1985), pp. 405-406

- ↑ Dictionary of American Fighting Ships, Puritan

- ↑ Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-second congress. 1872. pp. 1–. http://books.google.com/books?id=5qMFAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PA2.

- ↑ United States Naval Institute (1913). Naval Institute proceedings. pp. 1230–2. http://books.google.com/books?id=MilKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1230.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 McFeely (1974), p. 153

- ↑ Muench, James F. (2006). Five stars: Missouri's most famous generals. p. 74. http://books.google.com/books?id=PKvpsMbH5goC&pg=PA74.

- ↑ Grant, Ulysses S.; Simon, John Y. (2005). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. 27. pp. 63–4. http://books.google.com/books?id=nQstPeWppxsC&pg=PA63.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Dictionary of American Biography

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 New York Times (November 29, 1891), Mr. Robeson's Ambition

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 New York Times (July 9, 1885), Ex-Secretary Robeson Sued, Accessed on February 21, 2013

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans (1904), Robeson, George Maxwell

- ↑ An historical and genealogical account of Andrew Robeson (1916)

Sources[]

Books[]

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- O'Toole, G.J.A. (1984). The Spanish War: An American Epic--1898. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.. ISBN 0-393-30304-7.

Biographical Dictionaries[]

- "George Maxwell Robeson (1829 - 1897)". New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936.

- Rossiter Johnson, ed (1906). The Biographical Dictionary of America Robeson, George Maxwell. IX. p. 138. http://archive.org/stream/biographicaldict09johnuoft#page/n137/mode/1up.

- Rossiter Johnson and John Howard, ed (1904). "Robeson, George Maxwell". Boston, Massachusetts: The Biographical Society.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George M. Robeson. |

- George M. Robeson at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on 2008-02-12

- George Maxwell Robeson at The Political Graveyard

- "George M. Robeson". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/memorial/4868. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

The original article can be found at George M. Robeson and the edit history here.