The Genoese fleet at anchor in 1481.

The Genoese Navy (Italian language: Marineria genovese ), also known as the Genoese Fleet, was the naval contingent of the Republic of Genoa's military. From the 11th century onward the Genoese navy protected the interests of the republic and projected its power throughout the Mediterranean Sea.[1] The navy declined in power after the 16th century, periodically coming under the control of foreign powers, and was finally disbanded following the annexation of Genoa by the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in 1815.

History[]

Establishment[]

A center of trade since antiquity, the city of Genoa relied heavily on income from merchant shipping. Piracy posed a massive threat to the city's merchants, who were forced to pay soldiers to defend their ships. The city was likewise vulnerable to attack, a fact made apparent when in 935 a fleet led by Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Tamimi of the Fatimid sacked the city.[2] The Muslim incursion spurred the city to build up strong harbor defenses and renewed interest in an armed merchant marine. In 1005 the Republic of Genoa was established and the city was granted the status of Imperial City by the Holy Roman Empire. The new government was headed by a consul who would be elected every few years by the wealthiest merchant and landowners in the city. The young republic was as such dominated by the needs and desires of the merchant houses, and the navy was given a place of high importance in the new Thalassocracy. A High Admiral was appointed, and with the government coordinating the navy, Genoese traders and merchants came to dominate the Ligurian Sea in the 11th century. The city-state was considered one of the four Repubbliche Marinare in Italy alongside Venice, Pisa, and Amalfi. However, the early fleet lacked dedicated warships and was relegated to guarding the trade of the great merchant houses of Genoa, who continued to dominate the republic. In an effort to suppress piracy, the fleet was occasionally deployed to fight against Muslim corsairs from Aghlabid in North Africa.[3] After decades of disorder caused by the Norman conquest of southern Italy, the Genoese navy briefly captured the city of Mahdia in 1087.[4][5]

The beginning of the Crusades in 1095 resulted in a great period of profitability for Genoa. As new crusaders were constantly needed to secure the Holy Land (and later to reinforce the Crusader states), Genoa was able profit by assisting in the transport of military forces from Europe.[6] To better support the crusaders, a squadron of 12 Genoese galleys were deployed to the Holy Land during the First Crusade. The ships served to counter the threat posed by the Fatimid navy and saw some successes, with the fleet succeeding in trapping a Fatimid fleet in Beirut Harbor during the First Crusade. The Genoese Embriaco family became famous for their exploits in the Holy Land during this time, most notably for their leading of a Genoese seaborne attack during the Siege of Tripoli. In addition to receiving large amounts of loot from the crusader commanders, the republic established a number of Genoese trading colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Seas during the Crusades.[6] The Lebanese town of Byblos came completely under Genoese control, and the republic was entitled to 1/3 of the crusader-controlled city of Acre's income.[1] The Genonese fleet sheltered in these ports and defended them from pirates.[1] In the early 12th century the Genoese navy participated in the Pisan-led 1113–15 Balearic Islands expedition to suppress Majorcan piracy.[7]

At this time the fleet relied principally on two types of galleys, heavy Byzantine-style dromon (dromone), and lighter Italian-style galleys. This fleet was supplemented by armed merchant cogs.[8][9]

Mercantile conflicts[]

The Battle of Meloria (1284) established Genoese naval domination in the Western Mediterranean for nearly a century.

In addition to supporting the wars in the Holy Land, the navy played a vital role in the Genonese rivalry with the nearby Republic of Pisa, which competed with Genoa for influence in Corsica and Sardinia.[10] It was common for the Italian maritime states to prey on their rival's merchant shipping, and the Genoese navy was known to both suppress and participate in this practice.[11] In 1119 a Genoese squadron raided a Pisan merchant convoy, beginning the first of the Genoese-Pisan Wars. The first of the wars ended indecisively, but resulted in a century of raids and piracy as both cities fought over Corsica and Sardinia. In the 1230s a second, undeclared war erupted between Genoa and Pisa as part of the wider Guelphs-Ghibellines Conflict. The Holy Roman Emperor sided with Pisa when the war broke out, forcing Genoa to find allies abroad. The republic sided with the Pope (who was at the time in a dispute with the Holy Roman Emperor), and sent a fleet to transport a Guelph army to Rome in a show of support for the papal cause. The Ghibellines discovered the plan and, along with a Pisan fleet, intercepted the Genoese navy at the Battle of Giglio in 1241. Weighted down with passengers and baggage, the Genoese navy lost 3 galleys sunk and 27 captured.[12] The second war with Pisa ended in a white peace in 1243.

In the eastern Mediterranean, conflicts between Genoese and Venetian merchants in Acre resulted in the War of Saint Sabas being fought from 1256 to 1270.[13] During the conflict the Genoese navy was defeated in a series of pitched battles with Venice, and so it resorted to attacking merchant convoys instead of warships.[13][14] The disastrous defeats at the hands of Pisa and Venice hindered Genoese ambitions, but also led to the creation of a dedicated naval force in Genoa.[12] Larger galleys were built, the office of High Admiral was granted more powers, and the formidable Genoese crossbowmen were added to the crews of Genoese warships. When a third war broke out between Pisa and Genoa, the rebuilt Genoese fleet won a major victory at the 1284 Battle of Meloria, in which the Genoese captured 37 Pisan galleys and 9000 sailors.[15] The battle left Genoa the strongest naval power in the Western Mediterranean.[13]

Stern of a 17th century Genoese war-galley emblazoned with the white and red cross of Genoa.

With Pisa in a state of decline, Genoa expanded into Corsica and northern Sardinia. In 1266 Genoese merchants purchased the city of Kaffa from the Golden Horde and went on to establish further trading colonies in the Black Sea and Byzantine Empire. This expansion brought Genoa into further conflict with the powerful city-state of Venice, which also had trade relations in the area.[13] The bitter rivalry escalated into the first of the Venetian–Genoese wars in 1296, at which point Genoa's fleet consisted of 125 war-galleys. Despite outnumbering the Venetian navy, the Genoese fleet was unable to catch them, and the Republic's merchants suffered greatly during the war. A change came in 1298 when a major engagement was fought in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Korčula. In the Battle of Curzola a fleet of 75 Genoese galleys decisively defeated a force of 95 Venetian galleys, destroying or capturing 83 of the enemy ships. However, Genoese casualties were heavy and the city's shipyards were unable to quickly replace the ships lost at Curzola. The conflict ended in a relative stalemate in 1299. Following the war, Genoa dominated the Mediterranean slave trade and the Genoese navy employed thousands of galley slaves as oarsmen. This new policy decreased the cost of maintaining the navy, as rowers no longer had to be paid (as opposed to Venice, which only employed paid rowers), but also decreased the number of men available for boarding parties, as Genoese captains did not trust armed slaves.[16][17]

As Genoa continued to expand its trade network during the 14th century, the navy was increasingly employed to defend trade routes. While these naval trade routes greatly benefited the city, they also left it vulnerable to disease. In 1347 the Black Death was introduced to Kaffa during a Mongol siege and soon spread aboard fleeing Genoese ships.[18] A Genoese merchant fleet sailing from Kaffa spread the disease to Messina, from which city the plague spread to the rest of Europe.[19] Over 40,000 people in the city of Genoa died in the pandemic, a disaster that reduced the amount of money available to finance the fleet. Many sailors were also killed by the Black Death, leaving the navy undermanned.[20]

Genoese and Venetian fleets battling in the straits of Messina.

A third conflict with Venice began over trading disputes in the Black Sea in 1350. Venice allied itself with the Kingdom of Aragon and the Byzantine Empire, and in doing so mustered a large force that outnumbered the Genoese navy. Genoa won a costly victory at a battle in the Bosporus Straits in February 1352 that forced Byzantium to withdraw from the war. The tide of the war reversed when in 1353 the Genoese navy suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Alghero. The loss of the fleet sparked civil unrest in Genoa, further hampering the Republic's war effort.[21] To combat this discord, the republic was temporarily dissolved and Genoa came under the rule of the Duke of Milan. In November 1354 a Genoese fleet commanded by Admiral Paganino Doria surprised a Venetian fleet off the coast of Pylos. At the ensuing Battle of Sapienza Genoa sank or captured 35 Venetian galleys. A peace treaty was signed between Venice and Milan in 1355, bringing an end to the conflict. While the status quo in the east was maintained, the Kingdom of Aragon was able to establish itself as a major rival to Genoese domination of the Western Mediterranean.[22] Genoa broke free from Milanese control following the conclusion of the war, and the republic was reestablished.[23]

In 1378 the War of Chioggia broke out between Genoa and Venice, a conflict Genoa initiated to counter Venetian threats to the Republic's trade routes in the Black Sea. During the war, a large percentage of the navy was relegated to escorting transport ships from Genoa to Crimea. The Venetians took advantage of the absence of Genonese warships and raided coastal settlements under Genoese control. The Genoese navy suffered a defeat in 1378 when a squadron was destroyed by the Venetians off of the Cape d'Anzio. Genoa won a victory in May 1379, after which the fleet sailed to the port of Chioggia in the Adriatic and captured the city. The Genoese intended to use their new position at Choioggia to blockade the city of Venice, but on June 24, 1380 the navy was defeated and driven from the city by a Venetian relief force. 17 Genoese warships were captured in the ensuing rout, and the Genoese army was left stranded in Chioggia without supplies.[22] The Genoese garrison later surrendered the town, and the War of Chioggia soon ended in a status quo, having exhausted both Genoa and Venice. The Genoese navy lost vital sailors, ships, and was supplanted as the leading naval power in the Western Mediterranean by Aragon.[22]

Decline[]

The costly wars against Venice and the devastating impact of the Black Death greatly reduced the Genoese navy's strength. The rise of larger nation states also sapped the ability of the relativity small city-state to compete militarily. Genoa (with French support) launched a crusade against Tunisia in 1390, with the intent to protect Genoese trade colonies from Muslim pirates. During the war the Genoese navy provided ships while French knights laid siege to the fortress of Mahdi. The war was a success for the christian forces, but also resulted in the French gaining political influence in Genoa, which was pressured to declare itself a French fiefdom in 1396. The Genoese navy was brought under French control, and on 7 October 1403 was decisively defeated by Venice at the Battle of Modon after the Genoese fleet raided Venetian trade colonies. The Republic gained independence from France in 1409, but the prestige of the military had been severely damaged and the city remained of vital interest to both France and Aragon.[24] In 1435 a Genoese fleet was dispatched on the request of Milan to the town of Gaeta, which was besieged by Aragon. At the time the Duke of Milan and the King of Aragon were fighting as to who would control the Kingdom of Sicily. The Genoese fleet arrived at Gaeta and defeated the numerically superior Aragonese fleet at the Battle of Ponza. The Aragonese flagship was forced to surrender and King Alfonso V of Aragon was captured. Despite this setback, Aragon prevailed in the conflict and the Sicily came under Aragonese control, making passage through the Strait of Messina difficult and further disrupting Genoese naval activities.[24][25]

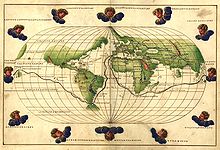

A map of the world in 1544 created by Genoese cartographer Battista Agnese.

Starting in the 15th century the Ottoman Empire began to expand at the expense of the Byzantine Empire and other countries friendly to Genoese merchants. The gradual loss of Imperial territory, coupled with the destruction of smaller Christian states such as Trebizond, Cyprus, and Amasra chipped away at Genoese mercantile interests in the Black Sea. The Ottomans constructed a massive fleet, and in doing so became the domiant naval power in the Eastern Mediterranean.[26] In 1453 Constantinople fell, and the Ottomans closed the Dardanelles and Hellespont to Christian shipping. This act cut the Genoese navy off from its bases in the Black Sea, and Genoa found itself isolated from the colonies that had for centuries provided the republic access to Russia and Central Asia.[27] With no way to return home and having had their lines of communication disrupted, the Genoese squadron in the Black Sea dispersed. Now indefensible, warehouses, fortresses, and ships built by the republic were lost. The former Genonese colonies were eventual annexed by regional powers, with Kaffa falling to the Ottomans in 1475.[28][29]

Despite the decline of the Genoese Navy and the Republic, Genoa's sailors remained in high regard. Cartographers and navigators such as Christopher Columbus, Battista Agnese, and Pietro Vesconte all hailed from the city state.[30]

Resurgence under Doria[]

Portrait of Admiral Andrea Doria, who advocated for a strong Genoese navy in the 16th century.

The Genoese navy saw a period of revival under the leadership of admiral and statesman Andrea Doria, who renewed interest in the navy. Doria was born in Genoa and served as a mercenary for various nations during his early life. He returned from service as a mercenary captain in 1503 to encourage Genoa to resist French encroachment, but failed and was forced to flee the city. From 1503 to 1522 Doria commanded a Genoese squadron in the Mediterranean against the Ottomans and the Barbary states. He fought against the Holy Roman Empire on behalf of France in 1522 before leading the Genoese fleet into Genoa and expelling the French in 1528. Doria then came into the service of the Holy Roman Empire and was granted the office of Imperial Admiral. Doria incorporated the Genoese navy into the Imperial navy and went on to defend the fortress of Koroni from the Ottomans and capture the city of Patras. A major victory over the Ottomans in the Battle of Girolata by the Genoese navy resulted in the capture of 11 galleys and Admiral Dragut. After retiring from military service, Doria worked to establish the Republic of Genoa as an autonomous state within the Holy Roman Empire, and in doing so gained the protection of the Emperor's army in return for providing the naval expertise of the Genoese. The Genoese economy began to shift from trade to banking and manufacturing as Portugal and Spain established their overseas empires, and Doria advocated that the Genoese navy should shift its doctrine from competition with other Christian nations to that of cooperation with other Europeans against Muslim piracy.

The revival period ended in the mid-16th century due to a series of military failures. The Imperial fleet was decisively defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Preveza in 1538, a Genoese fleet was damaged by a series of storms during the 1541 Algiers expedition, a Genoese-Spanish fleet was defeated at Ponza in 1552, and the navy failed to stop a French force from capturing Corsica in 1553. Genoa sent a contingent of her fleet to a christian alliance that was defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Djerba in 1560.[23] However, in 1571 the Genoese navy contributed 29 galleys (53 ships in total) to the Holy League fleet at the pivotal Battle of Lepanto, during which the Genoese admiral Giovanni Andrea Doria smashed the right flank of the Ottoman fleet. The decisive Christian victory ended Ottoman domination of the Mediterranean.[31]

1556 saw the republic create the Magistrato delle galee (magistrate of the galleys) to combat small-scale piracy.[32][33] looking to provide its sailors with durable clothing that could be worn wet or dry, the navy began to equip sailors with Genoese-produced denim jeans, and in doing so became one of the driving forces behind the adoption of the clothing.[34][35][36] During the 15th century competition between Genoa, Venice, Spain, and Portugal resulted in the creation of the Carrack. Genoa built a number of carracks during the 16th century and incorporated them into the navy.[37]

Coat of arms of the modern Italian Navy, the Marina Militare, which incorporates the Genoese flag (seen on the top right)

Further decline and disbandment[]

The decline of the Genoese navy and fleet continued through the 17th and 18th centuries. Changes in the economy of Genoa ensured that bankers, not merchants, became the strongest economic force in the city. The need to protect trade routes declined as a consequence, shrinking the need for a large navy.[38]

At the start of the Thirty Years' War the Genoese navy consisted of only 10 galleys. Genoa allied itself with Spain during the war, leading to France laying siege to the city in 1625. Spain launched an expedition to relieve Genoa, known as the Relief of Genoa. In 1684 the French navy bombarded the city, an act that devastated parts of Genoa and razed the Republic's shipyards.[39]

In 1742 the last possession of the Genoese in the Mediterranean, the island fortress of Tabarka, was lost to Tunis.[40]

On 14 March the last naval battle involving the Genoese navy took place. During the Battle of Genoa a French fleet with Genoese support was defeated by the British Royal navy off the coast of the city. Following the Napoleonic Wars, the city was granted to the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Genoese navy was officially disbanded on 3 January 1815, the day the city was annexed.[41][ISBN missing]

Legacy[]

The flags of the great Italian naval powers are incorporated into the ensign of the modern day Italian Navy. The cities represented include Genoa, Venice, Pisa, and Almafi.

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Giustiniani, Enrico. "STORIA DELLA CITTA’ DI GENOVA DALLE SUE ORIGINI ALLA FINE DELLA REPUBBLICA MARINARA". http://www.giustiniani.info/genova.html.

- ↑ Lev, Yaacov (1984). "The Fatimid Navy, Byzantium and the Mediterranean Sea, 909–1036 CE/297–427 AH". Byzantion. 54: 220–252. OCLC 1188035. pg. 232

- ↑ H. E. J. Cowdrey (1977), "The Mahdia campaign of 1087" The English Historical Review 92, pp. 1–29.

- ↑ Erdmann, Carl. The Origin of the Idea of Crusade, tr. Marshall W. Baldwin and Walter Goffart. Princeton University Press, 1977.

- ↑ Cowdrey, H. E. J. "The Mahdia Campaign of 1087." The English Historical Review, 92:362 (January, 1977), 1–29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Housley 2006, pp. 152–154

- ↑ Pirenne, Henri (2010-10-04) (in en). A History of Europe (Routledge Revivals): From the Invasions to the XVI Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781136879340. https://books.google.com/books?id=mp_HBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT193&lpg=PT193&dq=merger+of+genoese+and+venetian+fleets&source=bl&ots=lJUkX1y4Mh&sig=sV-1hx4XQS3V7EOA-UsrDXX79xw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjhwuLMqZjWAhXELyYKHQPwC-8Q6AEINTAE#v=onepage&q=merger%20of%20genoese%20and%20venetian%20fleets&f=false.

- ↑ "Genoa: The Cog in the New Medieval Economy - Medievalists.net" (in en-US). Medievalists.net. 2015-08-18. http://www.medievalists.net/2015/08/genoa-the-cog-in-the-new-medieval-economy/.

- ↑ "VENETIANS, GENOESE AND TURKS: THE MEDITERRANEAN 1300–1500". http://www.cogandgalley.com/2009/02/venetians-genoese-and-turks.html.

- ↑ David Abulafia, Rosamond McKitterick (1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1198-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 439. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- ↑ "Merchants and marauders : Genoese maritime predation in the twelfth-century Mediterranean - Alexandria Digital Research Library | Alexandria Digital Research Library" (in en). https://alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f3st7pnn.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Milman, Henry (1857). History of Latin Christianity Vol.IV. London.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Lane (1973), p. 73-78

- ↑ "Fleet Operations in the First Genoese-Venetian War, 1264-1266 » De Re Militari" (in en-US). http://deremilitari.org/2013/12/fleet-operations-in-the-first-genoese-venetian-war-1264-1266/.

- ↑ David Abulafia, Rosamond McKitterick (1999). p. 439.

- ↑ William Ledyard Rodgers (1967). Naval warfare under oars, 4th to 16th centuries: a study of strategy, tactics and ship design. Naval Institute Press. pp. 132–34. ISBN 0-87021-487-X.

- ↑ Steven A. Epstein, Speaking of Slavery: Color, Ethnicity, and Human Bondage in Italy (Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past.

- ↑ "Channel 4 – History – The Black Death". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ↑ "At the beginning of October, in the year of the incarnation of the Son of God 1347, twelve Genoese galleys were fleeing from the vengeance which our Lord was taking on account of their nefarious deeds and entered the harbour of Messina. In their bones they bore so virulent a disease that anyone who only spoke to them was seized by a mortal illness and in no manner could evade death. ...Not only all those who had speech with them died, but also those who had touched or used any of their things. When the inhabitants of Messina discovered that this sudden death emanated from the Genoese ships they hurriedly ordered them out of the harbor and town. But the evil remained and caused a fearful outbreak of death." Michael Platiensis (1357), quoted in Johannes Nohl (1926). The Black Death, trans. C.H. Clarke. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Michael of Piazza (Platiensis) Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas retulere Vol 1, p. 562, cited in Ziegler, 1998, p. 40.

- ↑ Thompson, William R. (1999) (in en). Great Power Rivalries. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570032790. https://books.google.com/books?id=qAZ4I-8tQIsC&pg=PA142&lpg=PA142&dq=Alghero+Genoese+defeat&source=bl&ots=VD8gi81wcG&sig=n-3g-ihazjiZ9NWfLWzw20qePaM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjMydmFnrfUAhUCdD4KHfOXCUEQ6AEIPjAF#v=onepage&q=Alghero%20Genoese%20defeat&f=false.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Sanderson, Michael W. B. Sea Battles: a Reference Guide. 1st American ed. Middletown, Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1975, p. 51.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Walton, Nicholas (2015-01-09) (in en). Genoa, 'La Superba': The Rise and Fall of a Merchant Pirate Superpower. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849046145. https://books.google.com/books?id=dXteCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT78&lpg=PT78&dq=war+galley+Genoa+museum&source=bl&ots=XRkiY0G2_H&sig=Oy3p8M-adsdwdA9p6zt0hxWYSFQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjfkeH9-b3UAhXC7YMKHSA5AZUQ6AEIVDAN#v=onepage&q=war%20galley%20Genoa%20museum&f=false.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 von Meerheimb, Richard (1865). Von Palermo bis Gaëta. Dresden.

- ↑ Simonde de Sismondi, Jean-Charles-Léonard (1832). A History of the Italian Republics. Philadelphia.

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500-1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p.23

- ↑ Ossian De Negri, Teofilo. Storia di Genova.

- ↑ Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton: University Press, 1978), pp. 343ff.

- ↑ The unknown holocaust of the Crimean Italians Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine. (in Italian) (in Russian) (in Ukrainian)

- ↑ Parry, John Horace (1981) (in en). The Age of Reconnaissance. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520042353. https://books.google.com/books?id=6l5rXRkpkFgC&pg=PA102&lpg=PA102&dq=genoese+cartographers&source=bl&ots=uImV6jv6cX&sig=CFfMPcx6I2iLGTDPHmbf99xYz1g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiAjMzFhtfVAhUG3IMKHZ0CBZ0Q6AEIPzAD#v=onepage&q=genoese%20cartographers&f=false.

- ↑ ISBN 1861899467, p. 70

- ↑ Genoese archives. https://www.archivesportaleurope.net/ead-display/-/ead/pl/aicode/IT-GE0429/type/fa/id/IT-ASGE-F90110376

- ↑ "Magistrato delle galee". http://dati.san.beniculturali.it/SAN/produttore_GGASI_san.cat.sogP.18376.

- ↑ "Genova - Heddels" (in en-US). Heddels. https://www.heddels.com/dictionary/genova/.

- ↑ Howard, Michael C. (2011-02-17) (in en). Transnationalism and Society: An Introduction. McFarland. ISBN 9780786486250. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qy4YtuIHsQcC&pg=PA235&lpg=PA235&dq=genoese+navy+jeans&source=bl&ots=HiAWDuCtEh&sig=F7yx5SQ-vpvMMmTkW9bp5yzsWAk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwju3aL8gdfVAhVsw4MKHVXGAfwQ6AEIVTAI#v=onepage&q=genoese%20navy%20jeans&f=false.

- ↑ "Jeans". http://facweb.cs.depaul.edu/sgrais/jeans.htm.

- ↑ Ancient and Modern Ships, Part 1: Wooden Sailing Ships by Holmes. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33098?msg=welcome_stranger.

- ↑ Bent, James Theodore (1881) (in en). Genoa: how the Republic Rose and Fell. C. K. Paul & Company. https://books.google.com/books?id=iJb2R-cY0fkC&pg=PA96&lpg=PA96&dq=balearic+expedition+genoa&source=bl&ots=81159t-aNI&sig=U1NV5nJj88fhFZx1p11FBiVb6AY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjBsNaJhMDUAhWF7oMKHWMcC9EQ6AEIPzAG#v=onepage&q=balearic%20expedition%20genoa&f=false.

- ↑ Genoa 1684, World History at KMLA

- ↑ Alberti Russell, Janice. The Italian community in Tunisia, 1861–1961: a viable minority. pag. 142.

- ↑ Wells, H. G., Raymond Postgate, and G. P. Wells. The Outline of History, Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956. p. 753

Bibliography[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Genoese Navy. |

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1189-5.

- Milman, Henry (1857). History of Latin Christianity Vol.IV. London. ISBN 9781115185141

- David Abulafia, Rosamond McKitterick (1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1198-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 439. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- Lane, Frederic Chapin (1973), Venice, a Maritime Republic, Johns Hopkins University, ISBN 0-8018-1445-6

- Ossian De Negri, Teofilo. Storia di Genova: Mediterraneo, Europa, Atlantico (2003). Florence: Giunti Editore. ISBN 978-88-09-02932-3.

- Steven A. Epstein (2002). Genoa and the Genoese, 958–1528. UNC Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 0-8078-4992-8.

- Campodonico, Pierangelo (1991) (in Italian). Marineria genovese dal Medioevo all'Unità d'Italia. Fabbri Ed.. ISBN 9788845041273.

The original article can be found at Genoese Navy and the edit history here.