| T | |

|---|---|

|

Location of T in

[[file:Template:Location map data|240px|Terracotta Army is located in Template:Location map data]]<div style="position: absolute; top: Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[".%; left: Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[".%; height: 0; width: 0; margin: 0; padding: 0;"><div style="position: relative; text-align: center; left: -Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[".px; top: -Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[".px; width: Template:Location map datapx; font-size: Template:Location map datapx; line-height: 0;" title="">[[File:Template:Location map data|Template:Location map dataxTemplate:Location map datapx|Terracotta Army|link=|alt=]] <div style="font-size: 90%; line-height: 110%; position: relative; top: -1.5em; width: 6em; Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[".">Terracotta Army (Template:Location map data)

| |

| Coordinates | 34°23′06″N 109°16′23″E / 34.384919°N 109.273108°ECoordinates: 34°23′06″N 109°16′23″E / 34.384919°N 109.273108°E |

| T | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 兵馬俑 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 兵马俑 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | soldier and horse funerary statues | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Terracotta Army or the "Terracotta Warriors and Horses", is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BC and whose purpose was to protect the emperor in his afterlife.

The figures, dating from around the late third century BC,[1] were discovered in 1974 by local farmers in Lintong District, Xi'an, Shaanxi province. The figures vary in height according to their roles, with the tallest being the generals. The figures include warriors, chariots and horses. Current estimates are that in the three pits containing the Terracotta Army there were over 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which are still buried in the pits near by Qin Shi Huang's mausoleum.[2] Other terracotta non-military figures were also found in other pits and they include officials, acrobats, strongmen and musicians.

Background[]

The Terracotta Army was discovered on 29 March 1974[3] to the east of Xi'an in Shaanxi province by a group of farmers when they were digging a water well around 1.6 km (1 mile) east of the Qin Emperor's tomb mound at Mount Li (Lishan),[4][5] a region riddled with underground springs and watercourses. For centuries, there had been occasional reports of pieces of terracotta figures and fragments of the Qin necropolis – roofing tiles, bricks, and chunks of masonry – having been dug up in the area.[6] This most recent discovery prompted Chinese archaeologists to investigate, and they unearthed the largest pottery figurine group ever found in China.

View of the Terracotta Army.

In addition to the warriors, an entire man-made necropolis for the Emperor has also been found around the first Emperor's tomb mound. The tomb mound is located at the foot of Mount Li as an earthen pyramid,[7] and Qin Shi Huangdi’s necropolis complex was constructed as a microcosm of his imperial palace or compound. It consists of several offices, halls, stables and other structures placed around the tomb mound which is surrounded by two solidly built rammed earth walls with gateway entrances. Up to 5 metres (16 feet) of reddish, sandy soil had accumulated over the site in the two millennia following its construction, but archaeologists found evidence of earlier disturbances at the site. During the digs near the Mount Li burial mound, archaeologists found several graves dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where diggers had apparently struck terracotta fragments which were then discarded as worthless back into the back-filled soil.[6]

According to historian Sima Qian (145–90 BC), work on this mausoleum began in 246 BC soon after Emperor Qin ascended the throne (then aged 13), and the full construction later involved 700,000 workers.[8] Geographer Li Daoyuan, six centuries after the death of the First Emperor, recorded in Shui Jing Zhu that Mount Li was a favoured location due to its auspicious geology: "... famed for its jade mines, its northern side was rich in gold, and its southern side rich in beautiful jade; the First Emperor, covetous of its fine reputation, therefore chose to be buried there".[6][9] Sima Qian, in his most famous work, Shiji, completed a century after the mausoleum completion, wrote that the First Emperor was buried with palaces, towers, officials, valuable artefacts and wonderful objects. According to this account, there were 100 rivers simulated with flowing mercury, and above them the ceiling was decorated with heavenly bodies below which were the features of the land. Some translations of this passage refer to "models" or "imitations," those words however weren't used in the original text with no mention of the terracotta army.[8][10]

The mound where the tomb is located.

Recent scientific work at the site has found high levels of mercury in the soil of the tomb mound,[11] giving some credence to Sima Qian's account of the emperor's tomb. The tomb of Shi Huangdi appears to be a hermetically sealed space that is as big as a football pitch and located underneath the pyramidal tomb mound.[12][13] The tomb remains unopened, one possible reason may be concerns about the preservation of valuable artifacts once the tomb is opened.[12] For example, after their excavation, the painted surface present on some figures of the terracotta army began to flake and fade.[14] In fact, the lacquer covering the paint can curl in 15 seconds once exposed to the dry air of Xi'an and can flake off in just four minutes.[15] Later historical accounts suggested that the tomb had been looted by Xiang Yu, a contender for the throne after the death of the Emperor,[16][17][18] however there are indications that the tomb may not have been plundered.[19]

Only a section of the site is presently excavated, and photos and video recordings are prohibited in some viewing areas. Only a few foreign dignitaries, such as Queen Elizabeth II, have been permitted to walk through the pits to observe the army at close quarters.

Construction of figures[]

A terracotta soldier with his horse.

The terracotta army figures were manufactured in workshops by government laborers and by local craftsmen, and the material used to make the terracotta warriors originated on Mount Li. The head, arms, legs and torsos were created separately and then assembled.[20] Studies show that eight face moulds were most likely used, and then clay was added to provide individual facial features.[21] Once assembled, intricate features such as facial expressions were added. It is believed that their legs were made in much the same way that terracotta drainage pipes were manufactured at the time. This would make it an assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, as opposed to crafting one solid piece and subsequently firing it. In those times of tight imperial control, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on items produced to ensure quality control. This has aided modern historians in verifying that workshops that once made tiles and other mundane items were commandeered to work on the terracotta army. Upon completion, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits in precise military formation according to rank and duty.

The terracotta figures are life-sized. They vary in height, uniform and hairstyle in accordance with rank. Most originally held real weapons such as spears, swords, or crossbows. The figures were also originally painted with bright pigments, variously coloured in pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white and lilac.[22][23] The coloured lacquer finish, individual facial features, and actual weapons used in producing these figures created a realistic appearance. Most of the original weapons were thought to have been looted shortly after the creation of the army, or have rotted away, and the colour coating has flaked off or greatly faded.

Pits[]

View of Pit 1, the largest excavation pit of the Terracotta Army.

There are four main pits associated with the terracotta army.[24][25] These pits are located about 1.5 km east of the burial mound and are about 7 metres deep. The army is placed as if to protect the tomb from the east, where all the Qin Emperor's conquered states lay. Pit one, which is 230 metres long and 62 metres wide,[25] contains the main army of more than 6,000 figures.[26] Pit one has 11 corridors, most of which are over 3 metres wide, and paved with small bricks with a wooden ceiling supported by large beams and posts. This design was also used for the tombs of noblemen and would have resembled palace hallways. The wooden ceilings were covered with reed mats and layers of clay for waterproofing, and then mounded with more soil making them, when built, about 2 to 3 metres higher than ground level.[27] Pit two has cavalry and infantry units as well as war chariots and is thought to represent a military guard. Pit three is the command post, with high-ranking officers and a war chariot. Pit four is empty, seemingly left unfinished by its builders.

Some of the figures in pit one and two showed fire damage and remains of burnt ceiling rafters have also been found;[28][29] these, together with the missing weapons, have been taken as evidence of the reported looting by Xiang Yu and its subsequent burning. The burning is thought to have caused the collapse of the roof which crushed the army figures below, and the terracotta figures presently displayed have been reconstructed from fragments of the crushed figures.

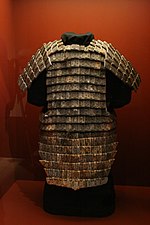

A large number of other pits which formed the necropolis have also been excavated.[30] These pits may lie within or outside the walls surrounding the tomb mound. These accessory pits variously contain bronze carriages, terracotta figures of entertainers such as acrobats and strongmen, officials, stone armour suits, burials sites of horses, rare animals and labourers, as well as bronze cranes and ducks in an underground park.[31]

Weaponry[]

<div class="thumb tright" style="width: Expression error: Unexpected < operator.px; ">

Weapons such as swords, spears, battle-axe, scimitars, shields, crossbows and arrowheads were found at the pits of the terracotta warriors.[24][32] Some of these weapons such as the swords are still very sharp and found to be coated with chromium oxide. This layer of chromium oxide is 10–15 micrometre thick and has kept the swords rust-free and in pristine condition after 2,000 years.[33][34][35] Many swords contain an alloy of copper, tin and other elements including nickel, magnesium, and cobalt.[36] Some carry inscriptions giving dates of manufacture between 245 and 228 BC, indicating they were actual weapons used in warfare before their burials.[37]

An important element of the army is the chariot, and four types of chariots were found. In battle the fighting chariots form pairs at the head of a unit of infantry. The principal weapon of the charioteers was the ge or dagger-axe, an L-shaped bronze blade mounted on a long shaft used for sweeping and hooking at the enemy. Infantrymen also carried ge on shorter shafts, ji or halberds, and spears and lances. For close fighting and defence, both charioteers and infantrymen carried double-edged straight swords. The archers carried crossbows with sophisticated trigger mechanisms capable of firing arrows over 800 meters.[37]

Exhibitions[]

Terracotta Warriors exhibition in San Francisco

A collection of 120 objects from the mausoleum and 20 terracotta warriors were displayed at the British Museum in London as its special exhibition "The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army" from 13 September 2007 to April 2008.[38] This Terracotta Army exhibition made 2008 the British Museum's most successful year, and made the British Museum the United Kingdom's top cultural attraction between 2007 and 2008.[39][40] The exhibition also brought in the most visitors to the British Museum since the King Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972.[39] It was reported that the initial batch of pre-bookable tickets to the Terracotta Army exhibition sold out so fast that the museum extended the exhibition until midnight on Thursdays to Sundays.[41] According to The Times, many people had to be turned away from the exhibition, despite viewings until midnight.[42] During the day of events to mark the Chinese New Year, the crush was so intense that the gates to the museum had to be shut.[42] The Terracotta Army has been described as the only other set of historic artifacts (along with the remnants of wreck of the RMS Titanic) which can draw a crowd by the name alone.[41]

A number of terracotta warriors and other artifacts were exhibited to the public at the Forum de Barcelona in Barcelona between 9 May and 26 September 2004, and it was their most successful exhibition ever.[43] The same exhibition was then presented at the Fundación Canal de Isabel II in Madrid between October 2004 and January 2005 and it was also their most successful ever by number of visitors.[44] From December 2009 to May 2010 the exhibition was shown in the Centro Cultural La Moneda in Santiago de Chile.[45]

The exhibition has travelled to North America and visited museums such as the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California, Houston Museum of Natural Science, High Museum of Art in Atlanta,[46] National Geographic Society Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.[47] Subsequently the exhibition travelled to Sweden and was hosted in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities between 28 August 2010 and 20 January 2011.[48][49] An exhibition entitled 'The First Emperor – China's Entombed Warriors', presenting 120 artefacts from the First Emperor's burial site, was hosted at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, between 2 December 2010 and 13 March 2011.[50] An exhibition entitled "L'Empereur guerrier de Chine et son armée de terre cuite" ("The Warrior-Emperor of China and his terracotta army"), featuring artifacts including statues from the First Emperor's mausoleum, was hosted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from 11 February 2011 to 26 June 2011.[51]

Gallery[]

See also[]

- List of World Heritage Sites in China

- Qin bronze chariot

Notes[]

- ↑ Lu Yanchou, Zhang Jingzhao, Xie Jun (1988). "TL dating of pottery sherds and baked soil from the Xian Terracotta Army Site, Shaanxi Province, China". pp. 283–286. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/1359018988900775.

- ↑ Jane Portal and Qingbo Duan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army, British Museum Press, 2007, p. 167

- ↑ Agnew, Neville (2010-08-03). Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Publications. p. 214. ISBN 9781606060131. http://books.google.com/books?id=n8YAyXzJE2IC&pg=PA214. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ O. Louis Mazzatenta. "Emperor Qin's Terracotta Army". National Geographic. http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/archaeology/emperor-qin/.

- ↑ The precise coordinates are 34°23′5.71″N 109°16′23.19″E / 34.3849194°N 109.2731083°ECoordinates: 34°23′5.71″N 109°16′23.19″E / 34.3849194°N 109.2731083°E)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3959-1. pp. 155, 157, 158, 160–161, 166. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Clements" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Clements" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 73号 Qin Ling Bei Lu (1970-01-01). "Google maps". Maps.google.co.uk. http://maps.google.co.uk/maps?f=q&source=embed&hl=en&geocode=&q=34.38130,+109.25365&aq=&sll=53.800651,-4.064941&sspn=14.588871,37.265625&ie=UTF8&t=h&ll=34.381864,109.254398&spn=0.004967,0.009098&z=16. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 6 《史记·秦始皇本纪》 Original text: 始皇初即位,穿治郦山,及并天下,天下徒送诣七十余万人,穿三泉,下铜而致椁,宫观百官奇器珍怪徙臧满之。令匠作机驽矢,有所穿近者辄射之。以水银为百川江河大海,机相灌输,上具天文,下具地理。以人鱼膏为烛,度不灭者久之。二世曰:"先帝后宫非有子者,出焉不宜。" 皆令从死,死者甚众。葬既已下,或言工匠为机,臧皆知之,臧重即泄。大事毕,已臧,闭中羡,下外羡门,尽闭工匠臧者,无复出者。树草木以象山。Translation: When the First Emperor ascended the throne, the digging and preparation at Mount Li began. After he unified his empire, 700,000 men were sent there from all over his empire. They dug down deep to underground springs, pouring copper to place the outer casing of the coffin. Palaces and viewing towers housing a hundred officials were built and filled with treasures and rare artifacts. Workmen were instructed to make automatic crossbows primed to shoot at intruders. Mercury was used to simulate the hundred rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, and the great sea, and set to flow mechanically. Above, the heaven is depicted, below, the geographical features of the land. Candles were made of "mermaid"'s fat which is calculated to burn and not extinguish for a long time. The Second Emperor said: "It is inappropriate for the wives of the late emperor who have no sons to be free", ordered that they should accompany the dead, and a great many died. After the burial, it was suggested that it would be a serious breach if the craftsmen who constructed the tomb and knew of its treasure were to divulge those secrets. Therefore after the funeral ceremonies had completed, the inner passages and doorways were blocked, and the exit sealed, immediately trapping the workers and craftsmen inside. None could escape. Trees and vegetations were then planted on the tomb mound such that it resembled a hill.

- ↑ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 《水经注·渭水》Original text: 秦始皇大兴厚葬,营建冢圹于骊戎之山,一名蓝田,其阴多金,其阳多美玉,始皇贪其美名,因而葬焉。

- ↑ Jane Portal and Qingbo Duan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army, British Museum Press, 2007, p. 17

- ↑ The first emperor: China's Terracotta Army Scientific Studies of High Level of Mercury in Qin Shihuangdi's tomb, by Duan Qingbo

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The First Emperor". Channel4.com. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/e-h/firstemperor4a.html. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Application of geographical methods to explore the underground palace of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum". Google. http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:DP-039QAig8J:ftp://124.42.15.59/ck/2011-01/165/096/062/464/On%2520the%2520Prediction%2520of%2520Heat%2520Transfer%2520Across%2520Turbulent%2520Liquid%2520Films.pdf+3d+reconstruction+of+underground+palace+of+qin+tomb&hl=en&gl=uk&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEESg0Uyt9EYlzOcxA4XPYGfq7TW0LnYcEIcuIYTgZmhVOmZ8iZAf5H9R-1IJN0SrEck4vRM60ZDAv0XbQ4dbqoASdO7bbLhZzYEGTKa607_9Sh6bCIFkEX_pirIG1BthOknVjKOe0&sig=AHIEtbQA1PhVFoMbOjCMjxcO_CUt_rYkDg. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Nature. "Terracotta Army saved from crack up". Nature.com. http://www.nature.com/news/2003/031127/full/news031124-7.html. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Larmer, Brook. "Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color." National Geographic June 2012: 86. Print

- ↑ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 《水经注·渭水》 Original text: 项羽入关,发之,以三十万人,三十日运物不能穷。关东盗贼,销椁取铜。牧人寻羊,烧之,火延九十日,不能灭。Translation Xiang Yu entered the gate, sent forth 300,000 men, but they could not finish carrying away his loot in 30 days. Thieves from northeast melted the coffin and took its copper. A shepherd looking for his lost sheep burned the place, the fire lasted 90 days and could not be extinguished.

- ↑ Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 8 《史记·高祖本纪》 Original text: 项羽烧秦宫室,掘始皇帝冢,私收其财物 Translation Xiang Yu burned the Qin palaces, dug up the First Emperor's tomb, and expropriated his possessions.

- ↑ Han Shu《汉书·楚元王传》:Original text: "项籍焚其宫室营宇,往者咸见发掘,其后牧儿亡羊,羊入其凿,牧者持火照球羊,失火烧其藏椁。" Translation: Xiang burned the palaces and buildings. Later observers witnessed the excavated site. Afterwards a shepherd lost his sheep which went into the dug tunnel; the shepherd held a torch to look for his sheep, and accidentally set fire to the place and burned the coffin.

- ↑ "Royal Chinese treasure discovered". BBC News. 2005-10-20. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/4359774.stm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Upf.edu. 1979-10-01. http://www.upf.edu/materials/huma/central/abast/ledder.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Jane Portal and Qingdao Dan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Arm, British Museum Press, 2007, p. 170

- ↑ John Simpson, Greg Hurst 3 December 2011 12:01 am. "Terracotta soldier – in full colour". The Times. UK. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article2414695.ece. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Terracotta army emerges in its true colors". China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-09/09/content_11278335.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "The Necropolis of First Emperor of Qin". History.ucsb.edu. http://www.history.ucsb.edu/faculty/barbierilow/Courses/fall%20of%20qin%20and%20tomb/player.html. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 A Magic Army for the Emperor Lothar Ledderose

- ↑ "The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty and Terracotta Warriors and Horses". China.org.cn. 2003-09-12. http://www.china.org.cn/english/kuaixun/74862.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Jane Portal and Qingdao Dyan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Arm, British Museum Press, 2007, pp. 260–167

- ↑ "China unearths 114 new Terracotta Warriors". BBC News. 2010-05-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8676886.stm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Terra Cotta Warriors[dead link]

- ↑ "Terracotta Accessory Pits". Travelchinaguide.com. 2009-10-10. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/cityguides/xian/terracotta/pits.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Decoding the Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shihuang". China Daily. 2010-05-13-. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/m/daminggong/2010-05/13/content_9845517_3.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Exquisite Weaponry of Terra Cotta Army". Travelchinaguide.com. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/shaanxi/xian/terra_cotta_army/weapon_1.htm. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Bronze Weapons "Terracotta Warriors (Terracotta Army)". China Tour Guide. http://www.chinatourguide.com/xian/terracotta_warriors_details.html#Unearthed Bronze Weapons. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ Cotterell, Maurice. (2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Rochester: Bear and Company. ISBN 1-59143-033-X. Page 102.

- ↑ Zhewen Luo (1993). China's imperial tombs and mausoleums. Foreign Languages Press. p. 216. ISBN 7-119-01619-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=K5PpAAAAMAAJ&dq=qin+shi+huang+tomb+sword+chromium&q=swords+chromium. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Terracotta Warriors". National Geographic. 2009. http://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/terracottawarriors/assets/tcw-exhibition-eguide.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "The First Emperor - China's Terracotta Army". British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/PDF/Teachers_resource_pack_30_8a.pdf.

- ↑ The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army. The British Museum

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Higgins, Charlotte (2008-07-02). "Terracotta army makes British Museum favourite attraction". The Guardian. London. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/jul/02/design.heritage. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ "British Museum sees its most successful year ever". Best Western. 2008-07-03. Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20081011084803/http://www.bestwestern.co.uk/Editorial-News/Article/British-Museum-sees-its-most-successful-year-ever-401.aspx.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army (British Museum)". Great Exhibitions. 2008-02-09. Archived from the original on 2008-06-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20080622032035/http://www.greatexhibitions.co.uk/blog/the-first-emperor-chinas-terracotta-army-british-museum/.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Whitworth, Damian (2008-07-09). "Is the British Museum the greatest museum on earth?". The Times. London. http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/visual_arts/article4296037.ece. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ DesarrolloWeb (2007-04-19). "Los guerreros de Xian, en el Forum de Barcelona". Guiarte.com. http://www.guiarte.com/noticias/los-guerreros-de-xian-en-el-forum-de-barcelona.html. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Guerreros de Xian". Futuropasado.com. http://www.futuropasado.com/?p=198. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Llegan a Chile los legendarios Guerreros de Terracota de China". Latercera.com. http://latercera.com/contenido/727_202192_9.shtml. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "Record-Breaking Terracotta Army Exhibition at Atlanta museum". http://www.guangzhouhotel.com/news/Terracotta_Army_Exhibition.shtml. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ↑ "ROM's terracotta warriors show a blockbuster". CBC. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. http://web.archive.org/web/20110108141021/http://www.cbc.ca/arts/artdesign/story/2011/01/06/terracotta-warriors-rom-attendance.html.

- ↑ "China's Terracotta Army, Stockholm, Sweden, Reviews". http://www.nileguide.com/destination/stockholm/local-events/china-s-terracotta-army/14617. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "World Famous Terracotta Army Arrives in Stockholm for Exhibition at Ostasiatiska Museum". http://www.artdaily.com/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=40000. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Terracotta warriors, Picassos heading to Sydney". ABC News. 14 October 2010. http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/10/14/3038261.htm. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ↑ "Empereur Guerrier De Chine Et Son Armee De Terre Cuite". Mbam.qc.ca. http://www.mbam.qc.ca/empereurdechine/index.html. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

Bibliography[]

- Debainne-Francfort, Corrine (1999). The Search for Ancient China. Discoveries. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-2850-3.

- Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Durham East Asia series. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0439-2.

- Kinoshita, Hiromi (2007). Jane Portal. ed. The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army. London: British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-2447-6.

- Ledderose, Lothar (2000). "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00957-5. http://www.scribd.com/doc/6694321/LedderoseA-Magic-Army-for-the-Emperor.

- Perkins, Dorothy (1999). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4374-3.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terracotta Army. |

- UNESCO description of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor

- Official Website of the Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shihuang

- People's Daily article on the Terracotta Army

- Microsoft Photosynth Experience of the Terra Cotta Warriors

- OSGFilms Video Article : Terracotta Warriors at Discovery Times Square

- The Necropolis of the First Emperor of Qin Excerpt from lecture

- China's Terracotta Warriors Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

The original article can be found at Terracotta Army and the edit history here.