| Millard Fillmore | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 13th President of the United States | |||

In office July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853 | |||

| Vice President | None | ||

| Preceded by | Zachary Taylor | ||

| Succeeded by | Franklin Pierce | ||

| 12th Vice President of the United States | |||

In office March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850 | |||

| President | Zachary Taylor | ||

| Preceded by | George Dallas | ||

| Succeeded by | William King | ||

| 14th Comptroller of New York | |||

In office January 1, 1848 – February 20, 1849 | |||

| Governor | John Young Hamilton Fish | ||

| Preceded by | Azariah Flagg | ||

| Succeeded by | Washington Hunt | ||

| Member of the United States House of Representatives | In office March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1843 | ||

| Preceded by | Thomas C. Love | ||

| Succeeded by | William Moseley | ||

In office March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1835 | |||

| Preceded by | Constituency established | ||

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Love | ||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | January 7, 1800 Summerhill, New York, U.S. | ||

| Died | March 8, 1874 (aged 74) Buffalo, New York, U.S. | ||

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery Buffalo, New York | ||

| Political party | Know Nothing (1856–1860) | ||

| Other political affiliations |

Anti-Masonic (Before 1832) Whig (1832–1856) | ||

| Spouse(s) | Abigail Powers (1826–1853) Caroline Carmichael (1858–1874) | ||

| Children | Millard Mary | ||

| Profession | Lawyer | ||

| Religion | Unitarian[1] | ||

| Signature | |||

| Military service | |||

| Service/branch | New York Guard | ||

| Battles/wars | Mexican-American War American Civil War | ||

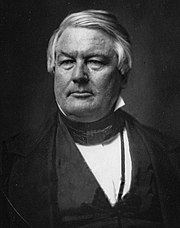

A younger Fillmore at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th President of the United States (1850–1853), and the last Whig President. As Zachary Taylor's Vice President, he assumed the presidency after Taylor's death.

He was a lawyer from western New York state, and an early member of the Whig Party. He served in the state legislature (1829-1831), as a U.S. Representative (1833-1835, 1837-1843), and as New York State Comptroller (1848-1849).

He was elected Vice President of the United States in 1848 as Taylor's running mate, and served from 1849 until Taylor's death in 1850, at the height of the "Crisis of 1850" over slavery.

Fillmore was an anti-slavery moderate; he opposed Abolitionist demands to exclude slavery from all of the territory gained in the Mexican War. Instead he supported the Compromise of 1850, which ended the crisis. In foreign policy, Fillmore supported U.S. Navy expeditions to "open" Japan, opposed French designs on Hawaii, and was embarrassed by Narciso López's filibuster expeditions to Cuba. He sought re-election in 1852, but was passed over for the nomination by the Whigs.

When the Whig Party broke up in 1854-1856, Fillmore and other conservative Whigs joined the American Party, the political arm of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic "Know-Nothing" movement, though he himself was not anti-Catholic. He was the American Party candidate for President in 1856, but finished third.

During the American Civil War, Fillmore denounced secession and agreed that the Union must be maintained by force if necessary, but was very critical of the war policies of President Abraham Lincoln. After the war he supported the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson.

He is consistently included in the bottom 10 of historical rankings of Presidents of the United States.

Fillmore co-founded the University at Buffalo[2] and helped found the Buffalo Historical Society, and Buffalo General Hospital.

Early life and career[]

Fillmore was born in a log cabin[3] in Moravia, Cayuga County, in the Finger Lakes region of New York State, on January 7, 1800, to Nathaniel Fillmore and Phoebe Millard, as the second of nine children and the eldest son.[4] He later lived in East Aurora, New York in the southtowns region, south of Buffalo.[5][6] Though Fillmore's ancestors were Scottish Presbyterians on his father's side and English dissenters on his mother's, he became a Unitarian in later life.[7] His father apprenticed him to cloth maker Benjamin Hungerford in Sparta, New York,[8] at age fourteen to learn the cloth-making trade. He left after four months, but subsequently took another apprenticeship in the same trade at New Hope, New York. He struggled to obtain an education living on the frontier and attended New Hope Academy for six months in 1819. There he fell in love with his future wife Abigail Powers.[9] Later that year, he began to clerk and study law under Judge Walter Wood of Montville.

Fillmore bought out his cloth-making apprenticeship, left Judge Wood, and moved to Buffalo, where he continued his studies in the law office of Asa Rice and Joseph Clary. He was admitted to the bar in 1823 and began his law practice in East Aurora, New York. In 1825, he built a house there for himself and Abigail. They were married on February 5, 1826. They had two children, Millard Powers Fillmore and Mary Abigail Fillmore.

In 1834, he formed a law partnership, Fillmore and Hall (becoming Fillmore, Hall and Haven in 1836), with close friend Nathan K. Hall (who would later serve in his cabinet as Postmaster General).[10] It would become one of western New York's most prestigious firms,[11] and exists to this day as Hodgson Russ LLP.

Fillmore was also a member of the New York Militia in the 1820s and 1830s, and served as Inspector of New York's 47th Brigade with the rank of Major.[12][13]

In 1846, he helped found the private University of Buffalo, which today is the public University at Buffalo, the largest school in the New York state university system.

Politics[]

Millard Fillmore helped build this house in East Aurora, New York, and lived here 1826–1830.

In 1828, Fillmore was elected to the New York State Assembly on the Anti-Masonic ticket, serving three one-year terms, from 1829 to 1831. In his final term he chaired a special legislative committee to enact a new bankruptcy law that eliminated debtors' prison. As the measure had support among some Democrats, he maneuvered the law into place by taking a nonpartisan approach and allowing the Democrats to take credit for the bill. This kind of inconspicuousness and avoiding the limelight would later characterize Fillmore's approach to politics on the national stage.

He was a follower and associate of Thurlow Weed, who had been a leading Anti-Mason. When Weed left the Anti-Masons in 1832, Fillmore did too; when Weed became the leading Whig organizer in New York, Fillmore also joined the Whigs. In 1832, he was elected U.S. Representative from New York's 32nd congressional district a "National Republican", serving in the 23rd Congress from 1833 to 1835. He was succeeded in 1834 by "Anti-Jacksonian" Thomas C. Love. Love declined renomination in 1836, and Fillmore was elected as a Whig (having followed his mentor Thurlow Weed into the party). He was re-elected twice, serving from 1837 to 1843, in the 25th, 26th, and 27th Congresses. He declined re-nomination in 1842.

In Congress, he opposed admitting Texas as a slave territory, he advocated internal improvements and a protective tariff, he supported John Quincy Adams by voting to receive anti-slavery petitions, he advocated the prohibition by Congress of the slave trade between the states, and he favored the exclusion of slavery from the District of Columbia.[14][15] He came in second place in the vote for Speaker of the House in 1841. He served as chair of the House Ways and Means Committee from 1841 to 1843 and was an author of the Tariff of 1842, as well as two other bills that President John Tyler vetoed.

After leaving Congress, Fillmore was the unsuccessful Whig candidate for Governor of New York in 1844. He was the first New York State Comptroller elected by general ballot, defeating Orville Hungerford 174,756 to 136,027 votes,[16] and was in office from 1848 to 1849. As Comptroller, he revised New York's banking system, making it a model for the future National Banking System.

Vice Presidency 1849–1850[]

Fillmore in 1849

The 1848 Whig National Convention nominated General Zachary Taylor (a slaveholder from Louisiana for President. This upset supporters of Henry Clay and "Consscience Whigs" opposed to slavery in territories gained in the Mexican–American War. A group of Whig pragmatists sought to balance the ticket, and the convention nominated Fillmore for Vice President. Fillmore came from a free state, had moderate anti-slavery views, and could help carry the populous state of New York.

Engraving of Millard Fillmore

Fillmore was also selected in part to prevent the nomination of the anti-slavery William H. Seward, and prevent Seward from receiving a position in Taylor's cabinet. (In an era where the President, Vice President and cabinet were expected to reflect geographic balance, Fillmore would "represent" New York, meaning another New Yorker (Seward) could not be in the cabinet.)[17][18][19]

The Taylor-Fillmore ticket won handily, but soon the nation was roiled by the "Crisis of 1850". Pro-slavery Southerners demanded that all of the new territories should be open to slavery. Anti-slavery Northerners demanded complete exclusion. The recently admitted state of Texas claimed a large part of New Mexico, and wanted the U.S. to assume the "national debt" of the former Republic of Texas. California settlers were petitioning for immediate admission as a free state, with no territorial stage. There were also disputes about slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia, about the apprehension of slaves who escaped to the free states, and about the territorial status of Utah, newly settled by the Mormons.

Fillmore presided over the Senate during the months of nerve-wracking debates over these issues. During one debate, enraged Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri stalked toward Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi, who brandished a pistol at Bentian.[20]

Taylor stunned his fellow Southerners by urging the immediate admission of California and New Mexico as free states. Ironically, it was Fillmore, the Northerner, who supported slavery in at least part of the territory to avoid an open break with the South. He wrote: "God knows that I detest slavery, but it is an existing evil ... and we must endure it and give it such protection as is guaranteed by the Constitution."

Clay constructed a compromise bill, which included provisions desired by both sides. Fillmore did not comment publicly on the merits of the compromise proposals. A few days before President Taylor's death, however, Fillmore suggested to the President that if the vote on Clay's bill was tied, he as President of the Senate would cast his tie-breakng vote in favor.[21]

Presidency 1850–1853[]

Domestic Affairs[]

Official White House portrait of Millard Fillmore

Taylor died suddenly on July 9, 1850, and Fillmore became President. The change in leadership also signaled an abrupt political shift. Taylor, it was thought, would have vetoed the Compromise bill (though some historians now doubt this). When Fillmore took office, the entire cabinet offered their resignations. Fillmore accepted them all and appointed men who, except for Treasury Secretary Thomas Corwin, favored the Compromise of 1850.[21] When the compromise finally came before both Houses of Congress, it was very watered down. As a result, Fillmore urged Congress to pass the original bill. This move only provoked an enormous battle where "forces for and against slavery fought over every word of the bill."[21] To Fillmore's disappointment the bitter battle over the bill crushed public support.[21] Clay, exhausted, left Washington to recuperate, passing leadership to Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. At this critical juncture, President Fillmore announced his support of the Compromise of 1850.[21]

On August 6, 1850, he sent a message to Congress recommending that Texas' debts be paid provided Texas abandoned its claims in New Mexico. This, and his deployment of 750 Federal troops to New Mexico, helped shift a critical number of northern Whigs in Congress away from their insistence upon the Wilmot Proviso—the stipulation that all the Mexican lands must be closed to slavery.

Douglas modified Clay's bill accordingly, and then split it into five separate Senate bills. These bills were:

- Admission of California as a free state.

- Settlement of the Texas boundary and debts.

- Creation of New Mexico Territory, which would be open to slavery.

- The Fugitive Slave Act.

- Abolition of the slave trade (but not slavery), in the District of Columbia.

Portrait of Millard Fillmore

Each measure obtained a majority, and, by September 20, President Fillmore had signed them into law. Daniel Webster wrote, "I can now sleep of nights." Only a few extremists on both sides denounced the Compromise. A slave-state convention called to discuss secession drew only a few delegates. Northerners were happy with the admission of California.

Nonetheless, the Compromise disrupted the Whig party, which did badly in the fall 1850 elections in the north. Northern Whigs were heard to say "God save us from Whig Vice Presidents." Fillmore's greatest difficulty was the Fugitive Slave Law: southerners complained bitterly about any slackness, but enforcement was highly offensive to northerners. Fillmore's solution was to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law, but also enforce the Neutrality Act of 1818 against filibustering Southerners who were trying ta make Cuba a slave state).

Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as the first governor of the Utah Territory in 1850.[22] In gratitude for creating the Utah Territory in 1850 and appointing Young as governor, Young named the territorial capital "Fillmore" and the surrounding county "Millard".[23]

Foreign affairs[]

In foreign affairs, Fillmore was particularly active in the Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at this time still prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American merchants and shipowners wanted Japan "opened up" for trade, and so that American ships could call there for food and water on voyages to Asia, and could put in there in emergencies without being punished. They were also concerned that American sailors cast away on the Japanese coast were imprisoned as crimimnals.[24]

American merchants saw in the British opening of China to trade an example of the "benefits of new trade markets."[24] Fillmore and Secretary of State Daniel Webster dispatched Commodore Matthew C. Perry to open Japan to relations with the outside world.[24] Though Perry did not reach Japan until after the end of Fillmore's term, Fillmore ordered the mission, and its success is to his credit.[24] Fillmore was also a staunch opponent of European meddling in Hawaii. France under Napoleon III attempted to annex Hawaii, but backed down after Fillmore issued strongly worded message suggesting that "the United States would not stand for any such action."[24]

Though President Taylor had signed the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty preventing Britain and the U.S. from acquiring new possessions in the Americas, Great Britain and the United States were still attempting to gain ground in the region.[24] The situation became tense enough that Fillmore ordered several warships to guard American merchants in an attempt to prevent British interference.[24]

Fillmore had difficulties regarding Cuba. Many southerners wanted to expand slave territory in the U.S. But the Missouri Compromise and other laws prevented that. Cuba was a colony of Spain where slavery was practiced. So some of these southerners tried to get Cuba annexed to the U,S. as a slave state.[24]

Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López recruited Americans for three "filibustering" expeditions to Cuba, in the hope of overthrowing Spanish rule there. His first attempt in 1849 was suppressed by U.S. officials by orders of President Taylor. López tried again a year later; he reached Cuba but was chased away by Spanish troops and disbanded his force in Key West. López and several of his followers were indicted for breach of the Neutrality Act, but were quickly acquitted by friendly Southern juries.[24]

Many southerners felt Fillmore should have supported the invasion, while some northern Democrats were upset at his apology to Spain. Framce and Britain dispatched warships to the region in response. Fillmore sent a stern warning saying that under certain conditions control of Cuba "might be almost essential to our [America's] safety."[24]

López tried a third time in 1851. This time his force was nearly all captured by the Spanish. He and many of his American followers were executed, provoking outrage among American sympathizers and further embarrassment for Fillmore.

Another issue that came up during Fillmore's presidency was the arrival of Lajos Kossuth, the exiled leader of a failed Hungarian revolution. Kossuth wanted the U.S. to recognize Hungary's independence. Many Americans were sympathetic to the Hungarian rebels, especially recent German immigrants, who were now coming to the U.S. in large numbers and had become a major political force. But this would require the U.S. to abandon its policy of nonintervention in European affairs. Despite the political pressure, Fillmore refused to change American policy, and decided to remain neutral.

Election of 1852 and completion of term[]

The election of 1852 came up, and Fillmore was unsure for a long time whether to run for a full term as President. He decided in early 1852 to run. The Whigs held their National Convention in June of that year. Fillmore at this time was unpopular with northern Whigs for signing and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. Fillmore led narrowly on the first few ballots, but was short of a majority and could gain no votes. Eventually General Winfield Scott went slightly ahead of Fillmore, and on the 52nd ballot, Daniel Webster's delegates switched to Scott, who was nominated.

Administration and cabinet[]

Statue of Fillmore outside City Hall in downtown Buffalo, New York

Judicial appointments[]

Presidential Dollar of Millard Fillmore

Supreme Court[]

Fillmore appointed the following Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States:

| Judge | Seat | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Benjamin Robbins Curtis | Seat 2 | September 22, 1851[25] | September 30, 1857 |

Other courts[]

Fillmore was able to appoint only four other federal judges, all to United States district courts:

| Judge | Court | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| John Glenn | D. Md. | March 19, 1852 | July 8, 1853 |

| Nathan K. Hall | N.D.N.Y. | August 31, 1852 | March 2, 1874 |

| Ogden Hoffman, Jr. | N.D. Cal. S.D. Cal. |

February 27, 1851 | July 23, 1866 January 18, 1854[26] |

| James McHall Jones | S.D. Cal. | December 26, 1850 | December 15, 1851 |

States admitted to the Union[]

- California – September 9, 1850

Later life[]

Fillmore/Donelson campaign poster

Fillmore's wife Abigail, who had been unwell for years, died March 30, 1853, less than month after he left office.

Fillmore was one of the founders of the University at Buffalo. The school was chartered by an act of the New York State Legislature on May 11, 1846, and at first was only a medical school.[27] Fillmore was the first Chancellor, a position he held as Vice President and as President. After leaving office, Fillmore returned to Buffalo and continued to serve as chancellor of the school.

In August 1854, Fillmore's daughter Mary died suddenly of cholera. Now left alone, Fillmore went abroad. While touring Europe in 1855, Fillmore was offered an honorary Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) degree by the University of Oxford. Fillmore turned down the honor, explaining that he had neither the "literary nor scientific attainment" to justify the degree.[28] He is also quoted as having explained that he "lacked the benefit of a classical education" and could not, therefore, understand the Latin text of the diploma, adding that he believed "no man should accept a degree he cannot read."[9]

Results by county explicitly indicating the percentage for Fillmore in each county.

When Fillmore returned to the U.S., the Whig Party had broken up over slavery issues and especially the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. Most former northern Whigs, including Fillmore's old mentor Weed, joined the new Republican Party.

Fillmore instead followed conservative and southern Whigs by joining the American Party, the political organ of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing movement.

Millard Fillmore during the Civil War.

Fillmore was not himself anti-Catholic – his daughter Mary had attended a girls' Catholic boarding school for a year.[29] But at this time, the American Party was the only alternative for non-Democrats who were not militantly anti-slavery.

The American Party chose Fillmore as its presidential nominee for the election of 1856. He thus sought a nonconsecutive second term as president (a feat accomplished only once, by Grover Cleveland). His running mate was Andrew Jackson Donelson, nephew of former president Andrew Jackson. Fillmore and Donelson finished third, carrying only the state of Maryland and its eight electoral votes; but he won 21.6% of the popular vote, one of the best showings ever by a third-party presidential candidate.

On February 10, 1858, Fillmore married Caroline McIntosh, a wealthy widow. Their combined wealth allowed them to purchase a big house in Buffalo, New York. They were noted for lavish hospitality in their home, until Mrs. Fillmore's health began to decline in the 1860s.

Fillmore helped found the Buffalo Historical Society (now the Buffalo History Museum) in 1862 and served as its first president.

In the election of 1860, Fillmore supported Constitutional Union Party candidate John Bell. He denounced secession, and supported the Union war effort. But Fillmore also became a constant critic of the war policies of President Lincoln, such as the Emancipation Proclamation.

He commanded the Union Continentals, a corps of home guards of males over the age of 45 from the upstate New York area. The Continentals trained to defend the Buffalo area in the event of a Confederate attack (such as the St. Albans Raid). They performed military drill and ceremonial functions at parades, funerals, and other events. The Union Continentals guarded Lincoln's funeral train in Buffalo. They continued operations after the war, and Fillmore remained active with them almost until his death.[30]

After the war, Fillmore maintained his conservative position. He supported President Andrew Johnson's conservative Reconstruction policies, and opposed the policies of the Radical Republicans.

He died at 11:10 pm on March 8, 1874, of the aftereffects of a stroke.[31] His last words were alleged to be, upon being fed some soup, "the nourishment is palatable." On January 7 each year, a ceremony is held at his grave site in the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo.

Legacy[]

Some northern Whigs remained irreconcilable, refusing to forgive Fillmore for having signed the Fugitive Slave Act. They helped deprive him of the Presidential nomination in 1852. Within a few years it was apparent that although the Compromise had been intended to settle the slavery controversy, it served rather as an uneasy sectional truce. Robert J. Rayback argues that the appearance of a truce, at first, seemed very real as the country entered a period of prosperity that included the South.[32] Although Fillmore, in retirement, continued to feel that conciliation with the South was necessary and considered that the Republican Party was at least partly responsible for the subsequent disunion, he was an outspoken critic of secession and was also critical of President James Buchanan for not immediately taking military action when South Carolina seceded.[33]

Benson Lee Grayson suggests that the Fillmore administration's ability to avoid potential problems is too often overlooked. Fillmore's constant attention to Mexico avoided a resumption of the hostilities that had only broken off in 1848 and laid the groundwork for the Gadsden Treaty during Pierce's administration.[34] Meanwhile, the Fillmore administration resolved a serious dispute with Portugal left over from the Taylor administration,[35] smoothed over a disagreement with Peru, and then peacefully resolved other disputes with Britain, France, and Spain over Cuba.

A pink obelisk marks Fillmore's grave at Buffalo's Forest Lawn Cemetery.

At the height of this crisis, the Royal Navy had fired on an American ship while at the same time 160 Americans were being held captive in Spain. Fillmore and his State Department were able to resolve these crises without the United States going to war or losing face.[36]

Because the Whig party was so deeply divided, and the two leading national figures in the Whig party (Fillmore and his own Secretary of State, Daniel Webster) refused to combine to secure the nomination, Winfield Scott received it. Because both the north and the south refused to unite behind Scott, he won only four of 31 states, and lost the election to Franklin Pierce.

After Scott's defeat, the Whigs' decline continued, until the party broke up over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Know Nothing]]s appeared.

In the history of the U.S. Presidency, Fillmore inaugurated a new era. All previous Presidents had substantial personal fortunes, acquired either by inheritance, marriage, or (in Martin van Buren's case) by work as an attorney. Fillmore was the first of a long line of late nineteenth century chief executives, mostly lawyers, who acquired only modest wealth during their lives, were "distinctly middle class", and who spent most of their careers in public service.[37]

The myth that Fillmore installed the White House's first bathtub was started by H. L. Mencken in a joke column published on December 28, 1917, in the New York Evening Mail. (See Bathtub hoax.) In February 2008, a television commercial for a sales event by Kia Motors featured Millard Fillmore, referring to him as "Unheard of", repeated the bathtub hoax, and presented a Millard Fillmore bust as a "Soap-on-a-Rope".[38][39][40][41]

While Fillmore's letters and papers are owned by multiple institutions, including the Penfield Library of the State University of New York at Oswego, the largest surviving collection is in the Research Library at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.[42]

Places named after Fillmore[]

- Fillmore, New York.

- Fillmore Glen State Park, New York.

- Fillmore County, Minnesota.

- Millard Fillmore Elementary School, Moravia NY.

- Fillmore County, Nebraska.

- Millard County, Utah and its county seat, Fillmore, Utah.

- Fillmore Elementary School, Davenport, IA

- Millard Fillmore Gates Circle Hospital, Buffalo.

- Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital, Williamsville, New York.

- Millard Fillmore Academic Center at the University at Buffalo's Ellicott Complex.

- Fillmore Street in Pasadena, California

- Fillmore Street, and the surrounding neighborhood in San Francisco,[43] after which, in turn, the Fillmore Auditoriums were named, both East and West.

- Fillmore Street in Vandalia, Illinois

- Fillmore Park in Alexandria, Minnesota

- Fillmore Avenue in Buffalo, New York[44]

- Fillmore Avenue in Las Vegas, Nevada

- Fillmore Avenue in East Aurora, New York

- Fillmore Street in Bronx, New York

Fillmore Academy, Fillmore Avenue, Brooklyn

- Fillmore Avenue in Brooklyn, New York

- Fillmore Street on Staten Island, New York

- Fillmore Road in East Meadow, New York

- Fillmore Avenue in El Paso, Texas

- Fillmore Street in Hollywood, Florida

- Fillmore Street in Miami, Florida

- Fillmore Avenue in Cape Canaveral, Florida

- Fillmore Avenue Northeast in Palm Bay, Florida

- Fillmore Drive in Boynton Beach, Florida

- Fillmore Drive in Sarasota, Florida

- Fillmore Court in South Patrick Shores, Florida

- Fillmore Street in Dayton, Ohio

- Fillmore Avenue in Alexandria, Virginia

- Fillmore Road in Richmond, Virginia

- Fillmore Circle in Bon Air, Virginia

- Fillmore Street in Eugene, Oregon

- Fillmore Road in Fort Washington, Maryland

- Fillmore Drive in Silver Spring, Maryland

- Fillmore Circle in Buena Park, California

- Fillmore Road Southeast in Atlanta, Georgia

- Fillmore Road Northeast in Rio Rancho, New Mexico

Electoral history[]

United States presidential election, 1848

- Zachary Taylor/Millard Fillmore (Whig) – 1,361,393 (47.3%) and 163 electoral votes (16 states carried)

- Lewis Cass/William Orlando Butler (Democrats) – 1,223,460 (42.5%) and 127 electoral votes (15 states carried)

- Martin Van Buren/Charles Francis Adams, Sr. (Free Soil) – 291,501 (10.1%) and 0 electoral votes

United States presidential election, 1856

- James Buchanan/John C. Breckinridge (Democrats) – 1,836,072 (45.3%) and 174 electoral votes (19 states carried)

- John C. Fremont/William L. Dayton (Republicans) – 1,342,345 (33.1%) and 114 electoral votes (11 states carried)

- Millard Fillmore/Andrew Jackson Donelson (Know Nothing/Whig) – 873,053 (21.6%) and 8 electoral votes (1 state carried)

Plaques to Fillmore[]

Ancestors[]

| Ancestors of Millard Fillmore | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes[]

- ↑ American President: Millard Fillmore

- ↑ "Chancellors and Presidents of the University". University of Buffalo The State University of New York. http://library.buffalo.edu/archives/ubhistory/presidents.html. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ↑ The original log cabin was demolished in 1852, but in 1965, the Millard Fillmore Memorial Association, using materials from a similar cabin, constructed a replica, which is located in Fillmore Glen State Park in Moravia. "Millard Fillmore Log Cabin" American Presidents Life Portraits

- ↑ "Millard Fillmore". Millard Fillmore. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1257052070494645.

- ↑ Smyczynski, Christine A. (2005). "Southern Erie County – "The Southtowns"". Western New York: From Niagara Falls and Southern Ontario to the Western Edge of the Finger Lakes. The Countryman Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-88150-655-9.

- ↑ Smith, H. Perry, ed. (1884). History of the City of Buffalo and Erie County: With illustrations and biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers, Volume I. D. Mason & Co. pp. 547–8. http://www.archive.org/details/historycitybuff00smitgoog.

- ↑ Deacon, F. Jay (1999). "Transcendentalists, Abolitionism, and the Unitarian Association". Chicago. http://www.uua.org/ga/ga00/514.html. Retrieved December 28, 2006.[dead link]

- ↑ "A History of Livingston County, New York," by Lockwood R. Doty, 1876, pp. 673–676.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Facts on Millard Fillmore[dead link]

- ↑ Fillmore, Millard; Severance, Frank H. (1907). Millard Fillmore Papers. Buffalo Historical Society.

- ↑ Paletta, Lu Ann; Worth, Fred L (1988). The World Almanac of Presidential Facts. World Almanac Books. ISBN 0-345-34888-5.

- ↑ Roger Sherman Skinner, editor, The New-York State Register for 1830-1831, 1830, page 361

- ↑ Crisfield Johnson, Centennial History of Erie County, New York, 1876, page 384

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911) "Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Fillmore, Millard" Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.) Cambridge University Press

- ↑

"Fillmore, Millard". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- ↑ Hough, Franklin B. A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York (1854) pg. 435.

- ↑ Alan Brinkley, Davis Dyer, editors, The American Presidency, 2004, page 146

- ↑ Gregory A. Borchard, Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley, 2011, page 33

- ↑ Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's Indispensable Man, 2013, pages 107-110

- ↑ Coleman, James P. "Two Irascible Antebellum Senators: George Poindexter and Henry S. Foote," Journal of Mississippi History 46 (February 1984): 17-27

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Bahles, Gerald. "Millard Fillmore: Domestic Affairs." American President: Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ↑ "The American Franchise". American President, An Online Reference Resource. Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/fillmore/essays/biography/8. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ↑ Presidents and Prophets: The Story of America's Presidents and the LDS Church (Covenant, 2007)

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 24.9 Bahles, Gerald. "Millard Fillmore: Foreign Affairs." American President: Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ↑ Recess appointment; formally nominated on December 11, 1851, confirmed by the United States Senate on December 20, 1851, and received commission on December 20, 1851.

- ↑ Hoffman was reassigned several times, beginning on January 18, 1854, as the California federal courts were redistricted. Hoffman, Ogden Jr.[dead link] , Federal Judicial Center.

- ↑ "University at Buffalo bio". Ublib.buffalo.edu. http://ublib.buffalo.edu/archives/timeline/time1.html. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ↑ Millard Fillmore bio from the Internet Public Library

- ↑ First Lady Biography: Abigail Fillmore

- ↑ Buffalo Historical Society, Proceedings, Volumes 23-37, 1885, page 72

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Jones MD; Joni L. Jones PhD, RN. "Presidential Stroke: United States Presidents and Cerebrovascular Disease (Millard Fillmore)". Journal CMEs. CNS Spectrums (The International Journal of Neuropsychiatric Medicine). http://www.cnsspectrums.com/aspx/articledetail.aspx?articleid=605. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Rayback 1959, pp. 286–292

- ↑ Rayback 1959, pp. 420–422

- ↑ Grayson 1981, p. 120

- ↑ Grayson 1981, p. 83

- ↑ Grayson 1981, pp. 103–109

- ↑ "The Net Worth of the U.S. Presidents: From Washington to Obama". The Atlantic. May 2, 2010. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2010/05/the-net-worth-of-the-us-presidents-from-washington-to-obama/57020/. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Millard Fillmore’s Bathtub". Sniggle.net. December 28, 1917. http://sniggle.net/bathtub.php. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ↑ Kelly Wilson (November 6, 2008). "H. L. Mencken: "A Neglected Anniversary"". Members.aol.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 1998. http://web.archive.org/web/19981202063209/http://members.aol.com/zoticus/bathlib/menck/ambath.htm. Retrieved May 16, 2010.[dead link]

- ↑ "White House Plumbing". Theplumber.com. December 28, 1917. http://theplumber.com/white.html. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Plumbing History in The White House". Plumbingworld.com. December 28, 1917. http://plumbingworld.com/historywhitehouse.html. Retrieved May 16, 2010.[dead link]

- ↑ "Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Millard Fillmore Papers". http://www.bechs.org/library/FillmorePapers.pdf. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ↑ Lewis, Gregory (February 8, 1997). "Fillmore Street name change urged". SFGate.com. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/e/a/1997/02/08/NEWS10248.dtl&hw=jonestown&sn=164&sc=132. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ↑ Vaughan, Bill (March 17, 1974) "Vaughan at Large: Prunes and Fillmore have something in common" Great Bend Tribune (Kansas) page 4

References[]

- Holt, Michael F. "Millard Fillmore". The American Presidency. Eds. Alan Brinkley, Davis Dyer, 2004. pp. 145–151.

- Deusen, Van Glydon. "The American Presidency". Encyclopedia Americana. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- Overdyke, W. Darrell. The Know-Nothing Party in the South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950.

- Rayback, Robert J. Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President. Buffalo, New York: Buffalo Historical Society, 1959.

- Grayson, Benson Lee. The Unknown President: The Administration of Millard Fillmore. University Press of America, 1981.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: |

| Wikiquote has media related to: Millard Fillmore |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Millard Fillmore. |

- Millard Fillmore at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Millard Fillmore: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- First State of the Union Address

- Second State of the Union Address

- Third State of the Union Address

- White House Biography

- Biography by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos

- Works by Millard Fillmore at Project Gutenberg

- Millard Fillmore Internet Obituary[dead link]

- Millard Fillmore at Encyclopedia American: The American Presidency

- Essays on Fillmore and each member of his cabinet and First Lady

- Millard Fillmore at C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits

| |||||

The original article can be found at Millard Fillmore and the edit history here.