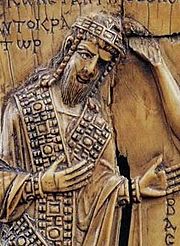

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in a 945 carved ivory.

De Administrando Imperio ("On the Governance of the Empire") is the Latin title of a Greek work written by the 10th-century Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VII. The Greek title of the work is Πρὸς τὸν ἴδιον υἱὸν Ρωμανόν ("For [my] own son Romanos"). It is a domestic and foreign policy manual for the use of Constantine's son and successor, the Emperor Romanos II.

Author and background[]

Constantine was a scholar-emperor, who sought to foster learning and education in the Eastern Roman Empire. He produced many other works, including De Ceremoniis, a treatise on the etiquette and procedures of the imperial court, and a biography of his grandfather, Basil I. De Administrando Imperio was written between 948 and 952.[1][2] It contains advice on running the ethnically-mixed empire as well as fighting foreign enemies. The work combines two of Constantine's earlier treatises, "On the Governance of the State and the various Nations" (Περί Διοικήσεως τοῦ Κράτους βιβλίον καί τῶν διαφόρων Έθνῶν), concerning the histories and characters of the nations neighbouring the Empire, including the Turks, Pechenegs, Kievan Rus', South Slavs, Arabs, Lombards, Armenians, and Georgians; and the "On the Themes of East and West" (Περί θεμάτων Άνατολῆς καί Δύσεως, known in Latin as De Thematibus), concerning recent events in the imperial provinces. To this combination were added Constantine's own political instructions to his son Romanus.

Content[]

The book content, according to its preface, is divided into four sections:[3]

- a key to the foreign policy in the most dangerous and complicated area of the contemporary political scene, the area of northerners and Scythians,

- a lesson in the diplomacy to be pursued in dealing with the nations of the same area

- a comprehensive geographic and historical survey of most of the surrounding nations and

- a summary of the recent internal history, politics and organization of the Empire.

As to the historical and geographic information, which is often confusing and filled with legends, this information is in essence reliable.[3]

The historical and antiquarian treatise, which the Emperor had compiled during the 940s, is contained in the chapters 12—40. This treatise contains traditional and legendary stories of how the territories surrounding the Empire came in the past to be occupied by the people living in them in the Emperor's times (Saracens, Lombards, Venetians, Serbs, Croats, Magyars, Pechenegs). Chapters 1—8, 10—12 explain imperial policy toward the Pechenegs and Turks. Chapter 13 is a general directive on foreign policy coming from the Emperor. Chapters 43—46 are about contemporary policy in the north-east (Armenia and Georgia). The guides to the incorporation and taxation of new imperial provinces, and to some parts of civil and naval administration, are in chapters 49—52. These later chapters (and chapter 53) were designed to give practical instructions to the emperor Romanus II, and are probably added during the year 951–52, in order to mark Romanus' fourteenth birthday (952).

Interpretation[]

Because De Administrando Imperio is one of the rare primary sources describing the medieval history of the Balkans, its text has been extensively analyzed by historians, sometimes concentrating on just a few sentences.[4]

Historians J. B. Bury in 1906, Gavro Manojlović in 1910, and Ljudmil Hauptmann in 1931 through 1942 published comprehensive analyses of the entirety of De Administrando Imperio which showed that it was written as a set of files each concentrating on different topics, dating from various time periods, that were subsequently redacted several times, causing the interpretation of the resulting text to vary significantly.[5]

The book's three similar but different accounts of the arrival of the Croats have confounded numerous historians since the 19th century.[6]

Historian Barbara M. Kreutz described the report found in the De Administrando Imperio that the Byzantines played a major role in the 871 fall of the Emirate of Bari as a probable concoction.[7]

Manuscripts and editions[]

The earliest surviving copy, (P=codex Parisinus gr. 2009) was made by John Doukas' confidential secretary, Michael, in the late 11th century. This manuscript was copied in 1509 by Antony Eparchus; this copy known as V=codex Vaticanus-Palatinus gr. 126, has a number of notes in Greek and Latin, added by late readers. A third complete copy, known as F=codex Parisinus gr.2967, is itself a copy of V, which was begun by Eparchus and completed by Michael Damascene; V is undated. There is a fourth, but incomplete, manuscript known as M=codex Mutinensis gr. 179, which is a copy of P made by Andrea Darmari between 1560 and 1586. Two of the manuscripts (P and F) are now located in Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and the third (V) is in the Vatican Library. The partial manuscript (M) is in Modena. The Greek text in its entirety was published seven times. The editio princeps, which was based on V, was published in 1611 by Johannes Meursius, who gave it the Latin title by which it is now universally known, and which translates as On Administering the Empire. This edition was published six years later with no changes. The next edition belongs to the ragusan Anselmo Banduri (1711) which is collated copy of the first edition and manuscript P. Banduri's edition was reprinted twice: in 1729 in the Venetian collection of the Byzantine Historians and in 1864 Migne republished Banduri's text with a few corrections.

Constantine himself had not given the work a name, preferring instead to start the text with the standard formal salutation: "Constantine, in Christ the Eternal Sovereign, Emperor of the Romans, to [his] own son Romanos the Emperor crowned of God and born in the purple".

Language[]

The language Constantine uses is rather straightforward High Medieval Greek, somewhat more elaborate than that of the Canonic Gospels, and easily comprehensible to an educated modern Greek. The only difficulty is the regular use of technical terms which, being in standard use at the time, may present prima facie hardships to a modern reader. For example, Constantine writes of the regular practice of sending basilikoí (lit. "royals") to distant lands for negotiations - in this case it is merely meant that "royal men", i.e. imperial envoys, were sent as ambassadors on a specific mission. In the preamble, the emperor makes a point that he has avoided convoluted expressions and "lofty Atticisms" on purpose, so as to make everything "plain as the beaten track of common, everyday speech" for his son and those high officials with whom he might later choose to share the work. It is probably the extant written text that comes closest to the vernacular employed by the Imperial Palace bureaucracy in 10th century Constantinople.

Modern editions[]

In 1892 R. Vari planned a new critical edition of this work and J.B. Bury later proposed to include this work in his collection of Byzantine Texts. He gave up the plan for an edition, surrendering it to Gyula Moravcsik in 1925. The first modern edition of the Greek text (by Gy. Moravscik) and its English translation (by R. J. H. Jenkins) appeared in Budapest in 1949. The next editions appeared in 1962 (Athlone, London) then in 1967 and 1993 (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington D.C.).

References[]

- ↑ Günter Prinzing; Maciej Salamon (1999). Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950-1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-3-447-04146-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=uZDgivj7_RAC&pg=PA24.

- ↑ Angeliki E. Laiou (1 January 1992). Byzantium: A World Civilization. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-88402-215-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=aQZAQAhFD20C&pg=PA8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ostrogorsky 1995, p. 105, note.

- ↑ Gračanin, Hrvoje (June 2008). "Od Hrvata pak koji su stigli u Dalmaciju odvojio se jedan dio i zavladao Ilirikom i Panonijom: Razmatranja uz DAI c. 30, 75-78" (in Croatian). Croatian Historical Society. p. 68. ISSN 1334-1375. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=57788&lang=en. Retrieved 2012-07-27. "Problem se u suštini svodi, što i nije rijetkost u povijesti hrvatskog ranosrednjovjekovlja, tek na usamljen navod iz literarnog vrela. U ovom slučaju to su dvije rečenice iz glasovita spisa koji je sredinom 10. stoljeća sastavio bizantski car Konstantin VII. Porfirogenet [...]"

- ↑ Grafenauer, Bogo (1952). "Prilog kritici izvještaja Konstantina Porfirogeneta o doseljenju Hrvata" (in Croatian translation of Slovene, with a summary in German). Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb. pp. 1–56. http://www.historiografija.hr/hz/1952/HZ_5_2_GRAFENAUER.pdf. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- ↑ Danijel Dzino (2010). Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia. BRILL. p. 104. ISBN 9004186468. http://books.google.com/books?id=6UbOtJcF8rQC&pg=PA104. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ Kreutz, 1996, 173 n45.

Sources[]

- De Administrando Imperio by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, edited by Gy. Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Washington D. C., 1993

- Kreutz, Barbara M. (1996). Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1587-7. http://muse.jhu.edu/books/9780812205435.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1995) [1969]. History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press.

External links[]

- Byzantine Relations with Northern Peoples in the Tenth Century

- Of the Pechenegs, and how many advantages accrue from their being at peace with the emperor of the Romans

- Chapters 29-36 at the Internet Archive

The original article can be found at De Administrando Imperio and the edit history here.