{{Infobox military conflict

| conflict = Battle of Crécy

| partof = the Hundred Years' War

| AKA = Battle of Cressy; Great Battle of the Hundred Years' War

| image =  | caption = Image from a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart's Chronicles

| date = 26 August 1346

| place = South of Calais, near Crécy-en-Ponthieu, Somme

| coordinates = 50°15′25″N 1°54′14″E / 50.257°N 1.904°ECoordinates: 50°15′25″N 1°54′14″E / 50.257°N 1.904°E

| result = Decisive English victory

Calais becomes an exclave of England.

| combatant1 =

| caption = Image from a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart's Chronicles

| date = 26 August 1346

| place = South of Calais, near Crécy-en-Ponthieu, Somme

| coordinates = 50°15′25″N 1°54′14″E / 50.257°N 1.904°ECoordinates: 50°15′25″N 1°54′14″E / 50.257°N 1.904°E

| result = Decisive English victory

Calais becomes an exclave of England.

| combatant1 = ![]() Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England![]() Holy Roman Empire

| combatant2 =

Holy Roman Empire

| combatant2 = ![]() Kingdom of France

Kingdom of France![]() Genoese]] mercenaries

Genoese]] mercenaries![]() Kingdom of Navarre

Kingdom of Navarre![]() Kingdom of Bohemia

Kingdom of Bohemia

[[File:Armoiries Majorque.svg|20px Kingdom of Majorca

| commander1 = ![]() Edward III of England

Edward III of England![]() Edward, the Black Prince

| commander2 =

Edward, the Black Prince

| commander2 = ![]() Philip VI of France (WIA)

Philip VI of France (WIA)![]() John of Bohemia†

| strength1 = 10,000–15,000

| strength2 = 20,000–25,000

| casualties1 = 100–300 at most

| casualties2 = c. 2,000 men-at-arms

John of Bohemia†

| strength1 = 10,000–15,000

| strength2 = 20,000–25,000

| casualties1 = 100–300 at most

| casualties2 = c. 2,000 men-at-arms

unknown number of common soldiers

}}

| |||||

| |||||

The Battle of Crécy (occasionally written in English as the "Battle of Cressy") took place on 26 August 1346 near Crécy in northern France. It was one of the most important battles of the Hundred Years' War because of the combination of new weapons and tactics used.

The English knights knew the importance of being willing to fight dismounted elbow to elbow with the pikeman and archers, a procedure which was learned from the earlier Saxons and also by their battles with the Scots from whom they learned tactical flexibility and the adaptation to difficult terrain.[1]

All of these factors made Edward III's army powerful, even when outnumbered by the French forces.[2]

Background[]

The Battle of Sluys on 24 June 1340, the first great battle of the Hundred Years' War, involved infantry fighting each other aboard ships moored side by side. The French, accompanied by Genoese troops, lost the battle, giving the English the freedom of the seas.[3]

In the years following Sluys, Edward attempted to invade France through Flanders, but failed due to financial difficulties and unstable alliances. Six years later, Edward planned a different route, and put into action a massive raid through Normandy, winning victories at Caen on 26 July and the Battle of Blanchetaque on 24 August. A French plan to trap the English force between the Seine and the Somme Rivers failed; the English escape led to the Battle of Crécy, one of the major battles of the war.[4]

Prelude[]

The English army landed at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue on 12 July 1346. Resistance to the landing was light, in part because a contingent of five hundred Genoese crossbowmen had withdrawn from the French forces only a few days previously due to a lack of pay.[5] After approximately six days, the English army began their march through the Cherbourg peninsula with considerable pillaging as they advanced.[6] On 26 July the English took the town of Caen; Count d'Eu and other French nobles were captured. Edward then took Lisieux; but when the English neared Rouen, they found the French had destroyed the bridges. Edward proceeded along the Seine. At Poissy, the English repaired the bridge and crossed the river.[7] Edward III's army left Poissy and marched north, estimates were that they covered several miles per day and met only slight resistance by the French allies of King John's army. Edward was separated from his Flemish allies by the destroyed bridges. He received word of a tidal crossing across a shallow part of the Somme. The Meauz chronicle states that the entire army crossed in one hour. The French tried but could not follow as the tide had begun to rise and were forced to retreat to Abbeville on or about 25 August.[8]

The English army finally reached the forest of Crécy which was 4 or 5 miles (6.4 or 8.0 km) deep and 8 miles (13 km) long. They took to a small hill north of Crécy-en-Ponthieu. Just a short distance away was Wadicourt, which provided protection for their left flank. The right flank was close to an area beyond which was the River Maye. The location of the wagons and baggage carts is conjecture. The formation was described as three-dimensional. Estimates are that the English had, by this time, traveled approximately 300 miles (480 km) and rested the day before the battle. The French army did not rest, putting them at a disadvantage.[9]

The English army was divided into three divisions. The vanguard were led by Edward, the Prince of Wales, the central division by the King of England, Edward III and the rearguard by the William de Bohun, Earl of Northampton.[8]

Size of forces[]

The size of the forces are not known exactly. Some historians[which?] have agreed on estimates of around 10,000–15,000 on the English side and 20,000–25,000 on the French side. The size and composition of the English army is considered to be more exact, since there are administrative and financial documents that recorded the organization and transportation of the army that crossed the English Channel. The much higher figures given by contemporary chroniclers such as Jean Froissart (100,000) and Richard Wynkeley (80,000) have been described by historians as quite exaggerated and "unacceptable", going by the extant war treasury records for 1340.[10]

The English force consisted of around 2,700–2,800 men-at-arms, heavily armed and armored men that included the English King and various nobles with their retinues as well as lower-ranking knights and other contingents.[11] Accompanying them were around 11,000–12,000 other troops. The estimated composition of these varies somewhat; according to Clifford Rogers there were 2,300 Welsh spearmen, 7,000 Welsh and English foot archers and 3,250 mounted archers and hobelars (light cavalry);[12] Andrew Ayton puts his estimate at around 3,000 mounted archers and hobelars, 5,000 foot archers and an additional 3,500 other troops.[13] Jonathon Sumption believes the force was somewhat smaller, based on calculations of the carrying capacity of the transport fleet that was assembled to ferry the army to the continent. Based on this, he has put his estimate at around 7,000–10,000.[14]

French financial records from the Crécy campaign are lost, so the estimates are less certain, although there is consensus that it was considerably larger than the English. There were around 12,000 mounted men-at-arms, several thousand Genoese crossbowmen and "large, [al]though [an] indeterminate number of common infantry".[15] Several historians have accepted the figure of 6,000 Genoese mercenary crossbowmen.[16] The figure has been questioned by Schnerb as unlikely based on estimates on the number of available crossbowmen in all of France (2,000) in 1340, only a few years previously. That the city-states of northern Italy, or Genoa on its own, could have put several thousand mercenary crossbowmen at the disposal of the French king is described by Schnerb as "doubtful".[17] The contingent of common infantry soldiers are not known with any certainty, except that it was considerable and in the thousands.[18]

Nobles and men at arms at the battle[]

Crécy village sign

The young Prince of Wales had with him the Earl of Warwick, and the Earl of Oxford, Sir Godfrey de Harcourt, the Lord Raynold Cobham, Lord Thomas Holland, Lord Stafford, Lord Mauley, the Lord De La Warr, Sir John Chandos, Lord Bartholomew Burgherst, Lord Robert Neville, Lord Thomas Clifford, the Lord Bourchier and the Lord Latimer. In this first division, about eight hundred men-at-arms, two thousand archers, and a thousand Welshmen. They advanced in regular order to their ground, each lord under his banner and pennon, in the centre of his men. In the second division were the Earl of Arundel, the Lords Roos, Willoughby, Basset, St Albans, Sir Lewis Tufton, Lord Multon and the Lord Lascels.[19] Sir Thomas Felton, a member of the Order of the Garter, fought at the battles of Crécy and Poitiers.[20][21] Others included Sir Richard Fitz-Simon, Sir Miles Stapleton, the Earl of Northampton, the Earl Bowden, Sir John Sully and Sir Richard Pembrugge (Pembroke).[22]

In front of the French army were the Moisne of Basle, the Monk of Bazeilles, the lords of Beaujen and Noyles and Louis of Spain. The French army was led by Phillip VI, surrounding him were the Counts of Alençon, Flanders, Blois, the Duke of Lorraine, Jean de Hainaut and de Montmorency, and a gathering of the lords Moisne of Blasle related the location and formation of the English forces.[23]

Battle[]

The King of England decided they would go no farther and would wait for the enemy. He sent his best men to choose the exact site of the battle. It is also said that he chose this time to knight his son, Edward.[24]

The men had carried with them much food and wine from their prior victories and were allowed to prepare their weaponry and to rest before the battle. The French had no time to rest, a disadvantage in that the men were tired and the crossbowmen's equipment was still wet.[25]

As in previous battles against the Scots, Edward III dispersed his forces in an area of flat agricultural land, choosing high ground surrounded by natural obstacles on the flanks. The king installed himself and his staff in a windmill on a small hill that protected the rear, where he could direct the battle.

In a strong defensive position, the English King ordered that everybody fight on foot and deployed the army in three divisions; one commanded by his sixteen-year-old son, Edward, the Prince of Wales and known as the Black Prince. The longbowmen were deployed in a "V-formation" along the crest of the hill. In the period of waiting that followed, the English built a system of ditches, pits and caltrops to maim and bring down the enemy cavalry. The admonitions of the Earl Bowden[citation needed] were largely underestimated. His analysis of the effect of the archers was visually illustrated.[Clarification needed] Forcing the knights to fight on foot had several advantages: it prevented them from starting a premature charge, it ensured protection for the archers should the French manage to close the distance, it also ensured that the archers and supporting infantry stayed on the battlefield rather than running at the first opportunity (a common occurrence in medieval warfare).[19]

Map of the Battle of Crécy

Froissart's account[]

The French army, commanded by Philip VI was unrested and commenced fighting immediately after their arrival, rather than gathering their strength for a battle the next day. Philip stationed his crossbowmen, under Ottone Doria, in the front line, with the cavalry at the back. The French even left behind the pavises, the big wooden shields that were the only means of defence for the crossbowmen, in the wooden carts in the rear along with the other infantry.[26] Both decisions proved to be costly mistakes. Froissart, the French chronicler, gives an account of the action:

The English, who were drawn up in three divisions and seated on the ground, on seeing their enemies advance, arose boldly and fell into their ranks... You must know that these kings, earls, barons, and lords of France did not advance in any regular order... There were about fifteen thousand Genoese crossbowmen; but they were quite fatigued, having marched on foot that day six leagues, completely armed, and with their wet crossbows. They told the constable that they were not in a fit condition to do any great things that day in battle. The Count of Alençon, hearing this, was reported to say, "This is what one gets by employing such scoundrels, who fail when there is any need for them."[27]

— Chateaubriand, after Froissart's middle French, gives: "On se doit bien charger de telle ribaudaille qui faille au besoin"[28]

The first attack was from the French crossbowmen, who launched a series of volleys with the purpose of disorganizing and frightening the English infantry. This was accompanied by the sound of musical instruments, brought by Philip VI for use as scare tactics. The crossbowmen proved completely useless; with a shooting rate of around 1–2 bolts per minute, they were no match for the longbowmen, who could shoot five or six arrows in the same amount of time, and also had superior range due to their bows and higher elevation. Furthermore, the crossbowmen's weapons were damaged by the brief thunderstorm that had preceded the battle, while the longbowmen had unstrung their bows until the rain stopped – Froissart relates that they did not withdraw their bows from their covers or sheaths until the first volley from the Genoese failed: "Les archers anglois découvrent leurs arcs, qu'ils avoient tenus dans leur étui pendant la pluie".[28] The crossbowmen also did not have their pavises, which would have provided some cover for the men during the long reloading procedure, but they remained in the baggage train. Under the hail of English arrows, the crossbowmen suffered heavy losses and were unable to approach the English lines to where their crossbows would have been more effective. Their commanders, including Doria, died trying to rally their men. Frustrated and confused, the crossbowmen retreated. The knights and nobles, upon seeing the mercenaries routed, hacked them down as they came back to their lines.

Battle of Crécy (19th-century engraving)

De Venette's version[]

French chronicler Jean de Venette's account differs slightly. He places the time and day of the battle on "Saint Louis's Day, 1346, at the end of the ninth hour". He mentions the failure of the Genoese crossbows to function; he then states they were useless because they were wet and not given time to dry out. He also states that the French King ordered the massacre of the crossbowmen because of what he perceived as cowardice. De Venette blames this and the further disorder and confusion of the French on the "undue haste" of the French King. He describes the English longbowmen's arrows as "rain coming from heaven and the skyies which were formerly bright, suddenly darkened".[29]

By the time this contretemps ended, several volleys of longbow arrows had already fallen among the French. At this the French knights decided it was time to charge, and they ran over the retreating mercenaries in an unorganized way. At this point the mercenaries cut the strings of their crossbows, presumably to indicate surrender. The English and Welsh longbowmen continued shooting as the knights and men-at-arms advanced, and the French fell along the way.[30] The English cavalrymen were just behind the footsoldiers - another important difference from the French. The French cavalry was composed only of nobles.[31]

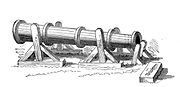

Ribaldis, a type of cannon, were first mentioned during preparations for the battle between 1345 and 1346.[32] Similar weapons appeared at the Siege of Calais in the same year, although it was not until the 1380s that the "ribaudekin" was mounted on wheels.[32] The use of firearms is only mentioned in one contemporary account of the battle, that of Giovanni Villani (d. 1348). Villani did travel abroad during much of the early 14th century, yet he had returned to his home in Florence at the time of the Battle of Crécy, so his information was likely second-hand, if not third- or fourth-hand. His account also conflicts with almost all of the other contemporary chronicles of this time on the events of the battle, specifically the use of firearms. In one of the later versions of his chronicle, Froissart does mention guns being used in the battle, but by that time firearms had become more common in warfare. His earlier versions fail to include any mention of firearms. So while they were perhaps employed, their possible effect on the battle should be viewed critically.[33]

English gun used at the Battle of Crécy

Froissart writes that English cannon made "two or three discharges on the Genoese", which is taken to mean individual shots by two or three guns because of the time necessary to reload such early, simple artillery.[32] These were believed to shoot large arrows and primitive grapeshot. The Florentine Giovanni Villani, agreed that they were destructive on the field, although he also indicated that the guns continued to fire upon French cavalry later in the battle:

The English guns cast iron balls by means of fire...They made a noise like thunder and caused much loss in men and horses... The Genoese were continually hit by the archers and the gunners... [by the end of the battle], the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls.[32]

With the crossbowmen neutralized, the French cavalry charged again in organized rows. However, the slight slope and man-made obstacles disrupted the charge. At the same time, the longbowmen continued shooting volleys of arrows upon the knights. Each time, more men fell, blocking successive waves of advance. The French attack fought bravely but could not break the English formation, and after several attempts, they had suffered many casualties. Edward III's son, the Black Prince, came under attack, but his father refused to send help, saying that he wanted him to "win his spurs". The prince subsequently proved himself to be an outstanding soldier. Philip himself was wounded, and at nightfall, ordered the French to retreat.[34]

Aftermath[]

The losses in the battle were highly asymmetrical. Contemporary sources provide total figures of losses for the French that are generally considered as exaggerated as those of the total size of the army, but convey the sense that casualties were immense. Although estimates vary, the English casualties in the battle were very light and perhaps only a tenth of those of the French army. An estimate by Geoffrey le Baker deemed credible by Michael Prestwich states that 4,000 French knights were killed.[35] According to a count after the battle, the bodies of 1,542 French knights and squires were found in front of where the lines commanded by the Prince of Wales, Sumption assumes another "few hundred" men-at-arms were cut down in the pursuit.[36] Ayton estimates that at least 2,000 French men-at-arms were killed, and notes that over 2,200 heraldic coats were taken from the field of battle as war booty by the English.[37] Besides the superior defensive tactics of the English army, the heavy losses on the French side are explained by the high chivalric ideals held by knights at the time. Nobles would have "preferred the likelihood of death or capture to a dishonourable flight", according to Ayton.[38] No exact figures for losses among common soldiers are mentioned anywhere, but are considered to have been heavy as well. All contemporary sources give very low casualty figures for the English.[39] Geoffrey le Baker gives among the highest estimates of around 300 English knights killed; overall, the casualties were counted in tens rather than hundreds.[40] While most historians consider the low English casualty figures to be improbably low, Rogers has argued that they are consistent with reports of casualties on the winning side in other medieval battles. The fighting style of the tight formations of foot soldiers, especially if they were heavily armored, generally meant very low casualties as long as they remained disciplined and kept in formation; it was when armies broke and fled the field that serious losses were incurred, and would often result in markedly lopsided victories. The death of knights and other nobility in battle generally also left traces in records, but only two Englishmen killed have been identified: the squire Robert Brente and the newly created knight Aymer Rokesley.[41] Two English knights were also taken prisoner, although it is unclear at what stage in the battle this happened.[40]

Fictional accounts[]

A fictional portrayal of the Battle of Crécy is included in the Ken Follett novel World Without End. The book describes the battle from an English knight's perspective, that of an archer, and from that of a neutral observer. This novel was made into a telefilm in 2012 and the Battle of Crécy is included, albeit in a very summarized form.

Another depiction can be found in Warren Ellis' & Raulo Caceres' graphic novel Crécy, which frames the battle as a narration by a Suffolk archer; or in Bernard Cornwell's fictional account of an archer in the Hundred Years' War, Harlequin (UK title), part of the Grail Quest novel series, or The Archer's Tale (US title). The lead character Thomas of Hookton, is an English archer who fights in the battle.[42]

The battle appears in "The campaign of 1346, as an historical drama" by Christopher Godmond.

It is also portrayed in Ronald Welch's Bowman of Crécy.

The protagonist, Edmund Beche, in P.C. Doherty's The Death of a King (1985) is present at the battle and describes it from the perspective of a bowman on the right flank near the village of Crécy.

In G. A. Henty's historical fiction book, St. George for England the main character is present at the battles of Cressy and Poitiers.

The battle is a crucial episode in the life of the hero Hugh de Cressi (his name is apparently a coincidence), in the H. Rider Haggard novel "Red Eve". The battle is described in some detail, including, for example the failure of the Genoese bowmen, attributed in the book, as above, to wet strings; and also the merciless treatment of the French wounded.

See also[]

- Medieval warfare

- Battle of Agincourt in 1415 for a similar battle won by English/Welsh longbowmen

- Battle of Poitiers (1356)

References[]

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 8, 12

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) Introduction p. 8

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 10

- ↑ Curry (2002), pp. 31-39.

- ↑ Ayton, The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 1

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 18

- ↑ Rothero (2005), pp. 4–6

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rothero (2005), pp. 5–6

- ↑ Rothero (2005), pp. 2–6

- ↑ Schnerb, "The French Army before and after 1346" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 269

- ↑ Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 189; Rogers (2000), p. 423

- ↑ Rogers (2000), p. 423

- ↑ Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy", in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 189

- ↑ Sumotion (1990) p. 497

- ↑ Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 18

- ↑ Lynn (2003), p. 74; Sumption (1990), p. 526

- ↑ Schnerb, "The French Army before and after 1346" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 268–69

- ↑ Curry (2002), p. 40; Lynn (2003), p. 74

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chronicles of England, France and Spain and the Surrounding Countries, by Sir John Froissart, Translated from the French Editions with Variations and Additions from Many Celebrated MSS, by Thomas Johnes, Esq; London: William Smith, 1848. pp. 160–171./

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography p308 col. 2/

- ↑ 67 (app c.1381) List of Members of the Order of the Garter/

- ↑ The chronciles of Froissart. Translated by John Bourchier, Lord Berners. Edited and reduced into one volume by G. C. Macauly former fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. (Macmillan & Co., Ltd 1904 not in copyright)) Chpt. CXXX pps. 104–106/

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 58

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 53–54

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 49, 50

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 66

- ↑ Amt (2001), p. 330.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Chateaubriand, 'Invasion de la France par Edouard', in Volume 7 from the complete works of 1834; p.37.

- ↑ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) p.43

- ↑ Amt (2001), p. 331.

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 17

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Nicolle (2000) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Nicolle" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Ayton & Preston (2005)

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 76–77

- ↑ Prestwich (1996), p. 331

- ↑ Sumption (1990), p. 530

- ↑ Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 19-20

- ↑ Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 25-26

- ↑ Prestwich (1996), p. 331; Rogers (2007), p. 215; Sumption (1990), p. 530

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy", in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 191

- ↑ Rogers (2007), p. 215

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Grail_Quest_%28novel_series%29

Bibliography[]

- Ayton, Andrew; Preston, Philip; et al. (2005). The Battle of Crecy, 1346. Boydell Press. http://www.boydell.co.uk/43833069.HTM.

- Amt, Emilie, ed (2001). Medieval England 1000–1500: A Reader. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-244-2.

- Curry, Anne Essential Histories: The Hundred Years' War 1337-1453. Osprey Publishing, Oxford; 2002.

- Lansing & English A Companion to the Medieval World. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford; (editors 2009).

- Lynn, John A. (2003), Battle: A History of Combat and Culture. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press.

- Nicolle, David (2000). Crécy 1346: Triumph of the longbow. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-966-2.

- Rogers, Clifford. War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327–1360. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2000.

- Rogers, Clifford J, Soldiers' Lives through History: The Middle Ages. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007.

- Rothero, Christopher The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers. Osprey Publishing, Oxford; 2005.

- Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volume I: Trial by Battle. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Primary sources[]

- The Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333–1381. Edited by V.H. Galbraith. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1927.

- Avesbury, Robert of. De gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi Tertii. Edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. London: Rolls Series, 1889.

- Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Eugene Deprez and Jules Viard. Paris: Honore Champion, 1977.

- Dene, William of. Historia Roffensis. British Library, London.

- French Chronicle of London. Edited by G.J. Aungier. Camden Series XXVIII, 1844.

- Froissart, Jean. Chronicles. Edited and Translated by Geoffrey Brereton. London: Penguin Books, 1978.

- Grandes chroniques de France. Edited by Jules Viard. Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1920–53.

- Gray, Sir Thomas. Scalacronica. Edited and Translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell. Edinburgh: Maclehose, 1907.

- Le Baker, Geoffrey. Chronicles in English Historical Documents. Edited by David C Douglas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Le Bel, Jean. Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Jules Viard and Eugène Déprez. Paris: Société de l'historie de France, 1904.

- Rotuli Parliamentorum. Edited by J. Strachey et al, 6 vols. London: 1767–83.

- St. Omers Chronicle. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, MS 693, fos. 248-279v. (Currently being edited and translated into English by Clifford J. Rogers)

- Venette, Jean. The Chronicle of Jean de Venette. Edited and Translated by Jean Birdsall. New York: Columbia University Press, 1953.

Anthologies of translated sources[]

- Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince. Edited and Translated by Richard Barber. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997.

- The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Edited and Translated by Clifford J. Rogers. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

Further reading[]

- Barber, Richard. Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine: A Biography of the Black Prince. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003.

- Belloc, Hilaire Crécy . Covent Garden, London: Stephen Swift and Co., LTD. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32196, 1912.

- Burne, Alfred H. The Crecy War: A Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1337 to the peace of Bretigny, 1360. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- DeVries, Kelly. Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 1996.

- Fowler, Kenneth (editor), The Hundred Years War.. Suffolk, UK: Richard Clay. The Chaucer Press, 1971.

- Hewitt, H.J. The Organization of War under Edward III. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1966.

- Keen, Maurice (editor), Medieval Warfare: A History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Ormrod, W.D. The Reign of Edward III. Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing, Inc, 2000.

- Packe, Michael. King Edward III. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul plc, 1985.

- Prestwich, Michael. Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Prestwich, Michael. The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1980.

- Reid, Peter. A Brief History of Medieval Warfare: The Rise and Fall of English Supremacy at Arms, 1314–1485. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2007.

- Rogers, Clifford J. Essay on Medieval Military History: Strategy, Military Revolution, and the Hundred Years War. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Variorum, 2010.

- Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337–1453. London, UK: Constable and Company Ltd, 1996.

- Waugh, Scott L. England in the reign of Edward III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

The original article can be found at Battle of Crécy and the edit history here.