Alfred Graf von Schlieffen

Alfred Graf[1] von Schlieffen, mostly called Count Schlieffen (German pronunciation: [ˈʃliːfən]; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist[2] who served as Chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in the 1905 Schlieffen Plan, the strategic plan for victory in a two-front war against the Russian Empire to the east and the French Third Republic to the west.

Biography[]

Schlieffen was born in Berlin on 28 February 1833 as the son of a Prussian army officer. He was part of an old Prussian noble family, the Schlieffen family.[3] He lived with his father, Major Magnus von Schlieffen, in their estate in Silesia.[3] Alfred von Schlieffen left to go to school in 1842. Growing up, Schlieffen showed no interest in joining the military and so he did not attend the traditional Prussian cadet academies.[3] Instead, he studied law at the University of Berlin.[3] While studying law, he enlisted in the army in 1853 for his required one-year compulsory military service.[4] After this, instead of joining the reserves, he was chosen as an officer candidate. Thus he started a long military journey, working his way up through the ranks, and lasting 53 years in service.

During the middle of Schlieffen's military duties, he married and had a family. He married his cousin Countess Anna Schlieffen in 1868. They had one healthy child, but after the birth of their second child, Anna died.[3] After his wife's death, Schlieffen focused all his attention on his military work.[5]

Military Service[]

On the recommendation of his commanders,[3] Schlieffen was admitted to the General War School in 1858 at age 25, particularly young compared to others. He graduated in 1861 with high honors which guaranteed him a role as General Staff officer. In 1862 he was assigned to the Topographic Bureau of the General Staff,[3] providing him with geographic knowledge that would help him devise the Schlieffen Plan. He was transferred to the actual German General Staff itself in 1865, though his role was initially minor. He first saw war as a staff officer with the Prussian Cavalry Corps in the Battle of Königgrätz of 1866 in the Austro-Prussian War.[3] The "battle of encirclement" tactic employed there would later figure in his Schlieffen Plan. During the Franco-Prussian War, he commanded a small army in the Loire Valley in what was one of the most difficult campaigns fought by the Prussian Army.[5] In France, Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden, promoted him to Major and head of the military-history division.[5] After years working alongside Helmuth von Moltke and Alfred von Waldersee, on 4 December 1886, he was promoted to Major General,[5] and shortly after replaced the retiring Moltke as Waldersee's Deputy Chief of Staff.[5] Not long after he became Quartermaster General, then Lieutenant General on 4 December 1888, and eventually General of the Cavalry (Germany) on 27 January 1893. After nearly 53 years of service, Alfred Von Schlieffen retired New Year's Day, 1906.[4] He died on 4 January 1913, just 19 months before the outbreak of World War I.[4] His last words are said to have been, "Remember: keep the right wing very strong."

Schlieffen Plan[]

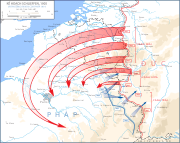

Schlieffen Plan

In 1894, Schlieffen came up with a strategical plan. It was modified in 1897 in which it was used as a power drive into Lorraine.[6] This was the first concept of the Schlieffen Plan. He introduced the idea of entering through the north of France and forcing the French down by using a wheel-like motion. Schlieffen was known for changing and modifying his plans; there were adjustments made almost every year up until the final plan was laid out.[7]

Given the fact that Germany was soon to face a battle, it was Schlieffen's responsibility to prepare his country for war. Schlieffen knew that if France and Russia formed an alliance, they could easily overpower Germany. Thus, in 1905, he outlined the Schlieffen Plan. It allowed Germany to avoid fighting a two-front war against the Franco-Russian alliance. The Schlieffen Plan would employ an early version ofBlitzkrieg—lightning warfare—to quickly overthrow France.[8] Knowing that the French always had a defensive strategy, Schlieffen devised the plan so that Germany would invade northern France by passing through Belgium and the Netherlands. While using minimum force to withstand Russian forces on the East, Germany would send troops to France and try to defeat them by using a giant flanking movement, by forcing France to fight while retreating south, or by forcing them to flee to Switzerland.[9] Germany could then send a vast majority of their troops to the Eastern front to fight a war against Russia. By attacking along the flanks of France, the plan would allow Germany to avoid many costly deaths, and force France off balance. He intended to roll up the French forces in a giant envelope, cut off northeastern France from the rest of the country and defeat the French in a decisive envelopment battle for Paris, thus forcing France into a humiliating surrender. Schlieffen envisioned that it would take roughly six weeks to knock France out of the war—the same amount of time he believed it would take Russia to fully mobilize. He then planned to turn the bulk of the German forces back to the east to catch the Russians off guard. Schlieffen was well aware that sending German troops through Belgium would bring the British into the war, thus eliminating any chance of localizing the war. However, he was confident that any British assistance would be too little and too late to make any difference.

In August 1905, Schlieffen was kicked by a companion's horse, making him incapable of battle.[10] During his time off, now at the age of 72, he started planning his retirement. His successor was yet undetermined. Von der Goltz was the primary candidate, but the Emperor was not fond of him.[10] A favourite of the Emperor was Helmuth von Moltke. He became the German Chief of staff after Schlieffen retired. During Schlieffen's absence, Moltke had ideas of his own. He inherited Schlieffen's ideas but disagreed with them in a few ways. He made a few insubstantial modifications. Upon Schlieffen's return, he insisted that France could be beaten only by a flank attack through Belgium.[11] Knowing this, Moltke still morphed the plan. The Schlieffen Plan was unsuccessfully used during World War I. Schlieffen did not live to witness the failure of his plan.[12]

Influence[]

Grave at the Invalidenfriedhof Cemetery, Berlin

Schlieffen was perhaps the best-known contemporary strategist of his time, although criticized for his "narrow-minded military scholasticism."

Schlieffen's operational theories were to have a profound impact on the development of maneuver warfare in the twentieth century, largely through his seminal treatise, Cannae, which concerned the decidedly un-modern battle of 216 BC in which Hannibal defeated the Romans. Cannae had two main purposes. First, it was to clarify, in writing, Schlieffen's concepts of maneuver, particularly the maneuver of encirclement, along with other fundamentals of warfare. Second, it was to be an instrument for the Staff, the War Academy, and for the Army all together.[13] His theories were studied exhaustively, especially in the higher army academies of the United States and Europe after World War I. American military thinkers thought so highly of him that his principal literary legacy, Cannae, was translated at Fort Leavenworth and distributed within the U.S. Army and to the academic community.

Along with the great militarist man we've known Schlieffen to be, there are also underlying traits about Schlieffen that often go untold. As we know, Schlieffen was a strategist. Unlike the Chief of Staff, Waldersee, Schlieffen avoided political affairs and instead was actively involved in the tasks of the General Staff.[5] These tasks included the preparation of war plans, and the readiness of the German Army for war. He focused much of his attention on planning. He devoted time to training, military education, and the adaptation of modern technology for the use of military purposes and strategic planning.[5] It was evident that Schlieffen was very much involved in preparing and planning for future combat. He considered one of his primary tasks was to prepare the young officers in not only a way in which they would accept responsibility for taking action in planning maneuvers, but also for directing these movements after the planning had taken place.[14] In regards to Schliffen's tactics, General Walter Bedell Smith, chief of staff to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in World War II, pointed out, General Eisenhower and many of his staff officers, products of these academies, "were imbued with the idea of this type of wide, bold maneuver for decisive results."

General Erich Ludendorff, a disciple of Schlieffen who applied his teachings of encirclement in the Battle of Tannenberg, once famously christened Schlieffen as "one of the greatest soldiers ever."

Long after his death, the German General Staff officers of the Interwar and World War II period, particularly General Hans von Seeckt, recognized an intellectual debt to Schlieffen theories during the development of the Blitzkrieg doctrine.

Quotations[]

- "A man is born, and not made, a strategist."—Schlieffen

- "To win, we must endeavour to be the stronger of the two at the point of impact. Our only hope of this lies in making our own choice of operations, not in waiting passively for whatever the enemy chooses for us."—Schlieffen

Notes[]

- ↑ Regarding personal names: Graf was a title, before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as Count. Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a separate estate, titles preceded the full name when given (Prinz Otto von Bismarck). After 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), could be used, but were regarded as part of the surname, and thus came after a first name (Otto Prinz von Bismarck). The feminine form is Gräfin.

- ↑ "Alfred Schlieffen, Graf von." ‘’Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition’’ (November 2011): 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), p. 128.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 V. J. Curtis, "Understanding Schlieffen," The Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin 6, no. 3 (2003), p. 56.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), 129.

- ↑ Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), p. 135.

- ↑ Walter, Goerlitz, History of The German General Staff (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), p. 132.

- ↑ Otto, Helmut. “Alfred Graf Von Schlieffen: Generalstabschef und Militärtheoretiker des Imperialistischen Deutschen Kaiserreiches Zwischen Weltmachstreben und Revolutionsfurcht.” Revue Internationale D'histoire Militaire no. 43 (July 1979): 74.

- ↑ Walter, Goerlitz, History of The German General Staff (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), 131.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Walter, Goerlitz, History of The German General Staff (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), 138.

- ↑ Walter, Goerlitz, ‘’History of The German General Staff’’ (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), 139.

- ↑ Otto, Helmut. Alfred Graf Von Schlieffen: Generalstabschef und Militärtheoretiker des Imperialistischen Deutschen Kaiserreiches Zwischen Weltmachstreben und Revolutionsfurcht.” Revue Internationale D'histoire Militaire no. 43 (July 1979): 74.

- ↑ Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), 132.

- ↑ Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), 133.

References[]

- Foley, Robert Alfred von Schlieffen's Military Writings. London: Frank Cass, 2003.

- Foley, Robert T. "The Real Schlieffen Plan", War in History, Vol. 13, Issue 1. (2006), pp. 91–115.

- Wallach, Jehuda L., The dogma of the battle of annihilation: the theories of Clausewitz and Schlieffen and their impact on the German conduct of two world wars. (Westport, Conn. ; London : Greenwood, 1986).

- Trevor, N. Dupuy, A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977), 128-134.

- Walter, Goerlitz, ‘’History of The German General Staff’’ (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), 128-140.

- Helmut, Otto. “Alfred Graf Von Schlieffen: Generalstabschef und Militärtheoretiker des Imperialistischen Deutschen Kaiserreiches Zwischen Weltmachstreben und Revolutionsfurcht.” ‘’Revue Internationale D'histoire Militaire’’ no. 43 (July 1979): 74

- "Alfred Schlieffen, Graf von." ‘’Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition’’ (November 2011): 1.

External links[]

| |||||

The original article can be found at Alfred von Schlieffen and the edit history here.